I

t could have been a party. At around two in the afternoon on Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, Doug Jones was making business calls from his room in Buenos Aires’ upscale CasaSur Palermo Hotel when clanging, banging, and whooping sounds erupted across the hall. “I heard some really bizarre noises, like yelling, and it sounded like someone was partying,” he says. Jones, a 36-year-old Texan in town for his friend Bret Watson’s destination wedding, eventually left the room. When he returned a few hours later, it seemed like his neighbor’s door wouldn’t stop slamming. “It sounded like people were coming and going nonstop,” Jones says. “It was happening every few minutes.” At one point, someone even tried opening Jones’ door until he yelled at them. But the ruckus continued. “[The shouting] just sounded manic, almost insane,” he says. “I heard the loudest one around five, and then I started hearing all the sirens.”

Several hours later, Jones learned the name of room 310’s occupant when a friend told him the guest had died. “I hate to say it, I’d never heard of Liam Payne,” Jones says. “But I looked him up, and I was like, ‘Oh, wow. This is not just anybody.’ ”

Payne was the handsome and charming pop sensation who melted England’s hearts on The X Factor as a teen in 2010. The judges selected him to be a member of One Direction, which formed that year on the show and became the biggest boy band since ’NSync and the Backstreet Boys. Payne sang the tender opening lines of the group’s breakout single, “What Makes You Beautiful,” and co-wrote hits like “Story of My Life,” “Midnight Memories,” and “Steal My Girl.” His 2017 solo track “Strip That Down” was certified triple platinum. Jones’ neighbor at CasaSur was a part of pop history, but at the time, he’d just seemed like a nuisance.

The singer had been staying at CasaSur since Oct. 13. Two days later, Jones was with Watson when the groom tried to check into room 310, a spacious suite with a balcony offering views of verdant Buenos Aires, which he’d booked six months earlier for his parents. But Watson, 34, says the front desk informed him that the room wasn’t available because there was another guest “they couldn’t get to check out.”

Watson was also largely unfamiliar with One Direction but had heard gossip from his friends about a celebrity guest behaving strangely. One friend told him Payne seemed desperate to be recognized. Another hotel guest who gave her name to the Daily Mail pseudonymously as Rebecca recalled Payne acting erratically and shouting, “I’m Liam. I used to be in a boy band. That’s why I’m so fucked up.”

“He was aggressive and loud,” a person who was in the lobby and requested anonymity says. “He had a frantic vibe.… It seemed like he was in a bad mental state.”

Watson says he saw Payne on the day of his death at around 4:30 p.m. lounging on a couch in the lobby until something on his laptop infuriated him. “Fuck this,” he yelled. He muttered incoherently and threw the computer on the floor. “The hotel staff got involved,” Watson says. “A number of people were able to escort him out of the lobby.” Watson says the staff appeared to take Payne back to his room to “prevent him from coming back down or causing any more scenes.” (Hotel management did not respond to requests for comment.)

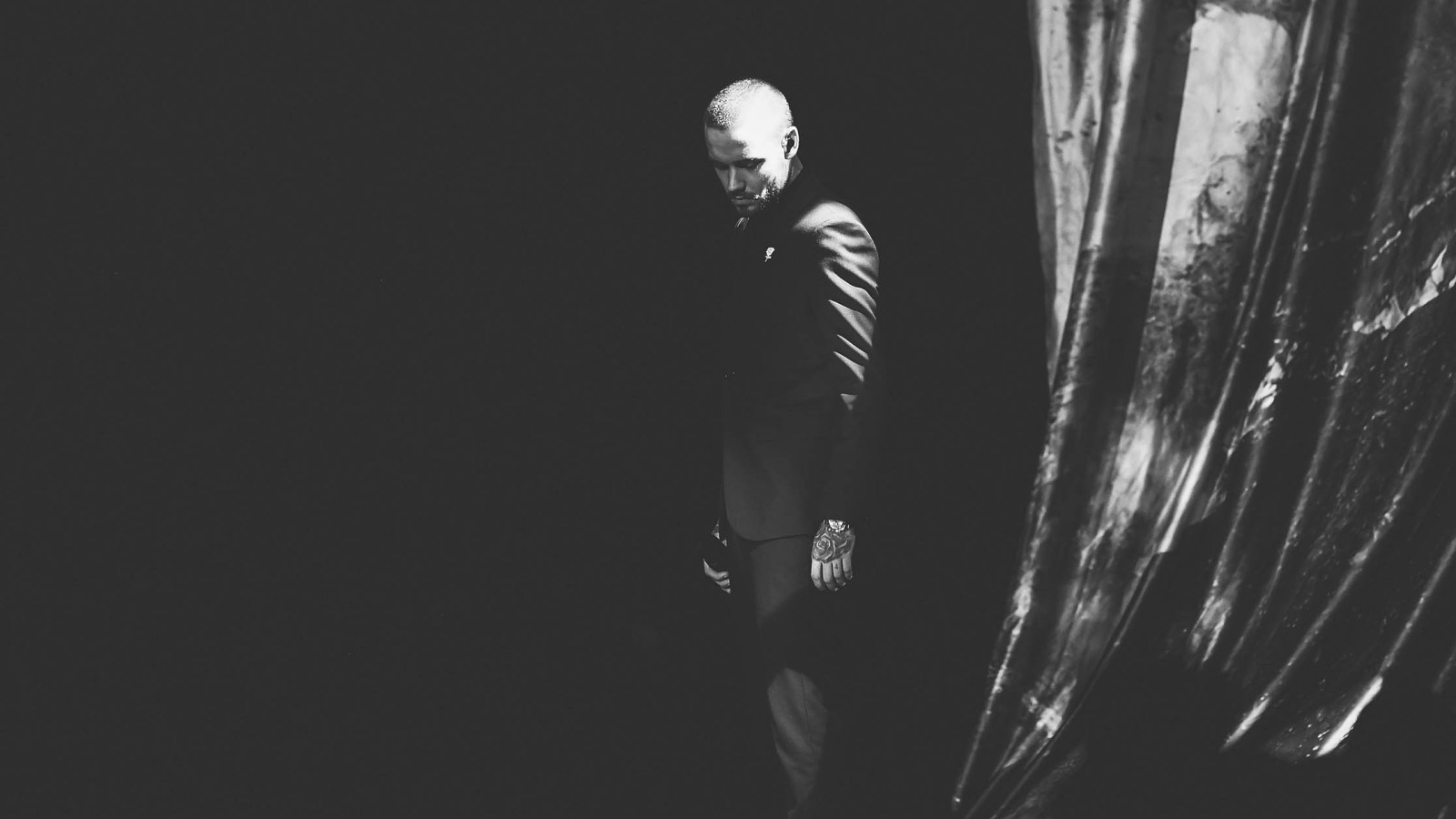

Cover photograph by Leigh Keily/Contour RA by Getty Images

But Payne was back in the lobby 15 minutes later. Watson remembers that he fell over a table, landed on the floor, and was “shaking or convulsing.” “He looked like he was in a semiconscious state,” Watson says. “That’s when the hotel staff rushed over to try and assist him; I think they were trying to speak with him or get him fully conscious.” As the staff carried him away, Payne threw himself on the floor and foamed at the mouth, according to Daniel Salinas, who was working as a masseur at the hotel that day. Leaked screenshots of security footage showed several men hoisting Payne’s limp body to the elevator.

“He was completely gone on drugs,” says Salinas, who helped move Payne to his room. “We grabbed him because there was no way to take him standing up.”

After the commotion, Watson returned to his room with his wedding planner, two floors below 310. They left the balcony door ajar; it was a nice day out. “Around 5 p.m.,” Watson says, “I saw an object fall out of the corner of my eye. Our wedding planner saw it straight on, and it looked like she went into shock. She goes, ‘Oh, my God. That was a body.’ ”

From the Apex of Stardom to the Lows of Addiction

Payne fell about 40 feet. The singer, age 31, died at approximately 5:07 p.m. of polytrauma and hemorrhaging caused by the fall. A preliminary toxicology report indicated Payne had alcohol, cocaine, and a prescription antidepressant in his system. Prosecutors in Buenos Aires would later say that Payne could have been in a state of semi- or complete unconsciousness.

Although the news sent shock waves around the world, anyone who was paying attention would have noticed the fraying threads of Payne’s life. A decade earlier, Payne was a beloved member of the world’s biggest boy band. In the years after One Direction, he struggled to sustain fame as he grappled with addiction. His only solo album, 2019’s LP1, didn’t live up to the promise of “Strip That Down.” After the pandemic, he was in and out of rehab and once showed up drunk to a podcast appearance. His ex-fiancée accused him of harassment and distributing nude photos of her as revenge porn. And Snapchat posts from the final weeks of his life suggested he was living in Florida, seemingly isolating himself with his girlfriend, influencer Kate Cassidy.

His final downward spiral included doing drugs in the wee hours with a waiter he’d met at a local restaurant, hiring two sex workers for a daytime orgy, and smashing the TV and furniture in his room. Accounts of Payne’s last hours reveal that while numerous people were in his orbit throughout the day — friends he texted, the sex workers, the wedding guests, passersby in the lobby, hotel staff — none were with him when he died.

In many ways, Payne’s life and death have the familiar contours of a pop tragedy: a young artist, whose talents were often at odds with his demons, experiencing the apex of stardom as well as its depths. But interviews with more than two dozen sources — including Payne’s friends, confidants, and collaborators; CasaSur hotel guests and employees; and sources close to prosecutors and defense attorneys — and a review of legal documents reveal the circumstances surrounding Payne’s final years are unsettling and murky. Could anyone have prevent this tragedy? It’s a question no one has yet been able to answer and the finger-pointing that has followed has only exacerbated the hurt and grief.

‘Liam’s Voice Is Warm, Solid, Trustworthy’

The goal was to assemble the ultimate boy band. It was Season Seven of The X Factor U.K., in July 2010, and judges Simon Cowell, Nicole Scherzinger, and Louis Walsh were poring over headshots. The trio had already lumped Harry Styles, Niall Horan, and Louis Tomlinson together (Zayn Malik would join later). When they got to Payne’s picture, Cowell remarked, “He was the standout audition.”

“I think he would definitely shine,” Scherzinger said. “I think that he could actually be the leader.”

“He thinks he’s better than anyone else,” Cowell observed with admiration.

“LIAM WAS A SWEET BOY WHO NEVER HAD A CHANCE TO MATURE.”

Payne, in many ways, did become One Direction’s leader. Songwriter-producer Carl Falk, who worked on 1D’s first three albums, has called Payne “the perfect song starter.” His voice was confident and suave with plenty of power but also a conversational ease. Payne split the opening verse with Styles on their signature song, “Story of My Life.” On “History,” the last song on One Direction’s last album, Made in the A.M., Payne guides the group to the final line, belting, “Baby, don’t know you? Baby, don’t you know? We can” — and then with everyone else — “live forever.”

Liam’s voice, “when you hear it, it’s warm, solid, it’s trustworthy,” One Direction’s former keyboardist and music director Jon Shone says. “It’s all these things that you need: It’s familiar, safe, and it’s there.”

Payne’s talent and confidence were innate but practiced. He was born on Aug. 29, 1993, in Wolverhampton, a city of less than a quarter-million people in England’s industrial Midlands. His parents, Geoff and Karen Payne, were a mechanical fitter and nursery nurse; he had two older sisters, Nicola and Ruth. (The Payne family, through a representative, declined to comment for this article.)

Payne came into the world with just one functioning kidney. “When I was born, I was effectively dead,” Payne said in the 2013 band autobiography One Direction: Our Story. He spent his first four years of life in and out of hospitals. At one point, he said, he was receiving “32 injections in my arm in the morning and evening to try and make me better.”

Chip Somers, a sober coach who worked with Payne in 2017 and 2018, remembers discussing the health condition with him. “If you’re going to put toxic substances through your body, and you’ve only got one [kidney], you need to be quite careful,” he says. “He was ill, unwell, for the early stages of his childhood, which probably had an impact on the relationships he developed with his family. He was in the hospital quite a lot.”

Growing up, Payne said, he never had a “tremendous amount of friends” and frequently hung out with his father. After being bullied in high school, he took up boxing to defend himself; he also learned to manage his medical issues well enough to become a top-ranked cross-country runner. But the kid who belted Oasis in his parents’ car, sang karaoke, and, at six years old, wowed a holiday camp with a rendition of Robbie Williams’ “Let Me Entertain You” always had his sights set on music.

Payne first auditioned for The X Factor in 2008. The baby-faced 14-year-old crooned “Fly Me to the Moon,” snapping his fingers and sneaking a cheeky wink at judge Cheryl Cole. Payne’s talent, ambition, and charisma got him through the first few rounds before he was sent home. Cowell was cautious, telling Payne at his audition that he had “potential,” but his voice lacked “grit” or “emotion.”

From left to right: “The X Factor UK”/youtube; Capital Pictures/MediaPunch/MediaPunch/IPx/ap images; David M. Benett/Getty Images, Andrew Chin/Getty Images; Ricky Vigil M/Justin E Palmer/GC Images; © Cristina Sille/dpa/ZUMA Press; Stephen Lock/i-Images/eyevine/redux

Determined to try out again, Payne spent the next two years focused on music. He worked with songwriters and producers, performed around town — from local pubs to a Premier League football-match halftime — and studied music technology at Wolverhampton College. Shone, who also grew up in the Midlands, points to the area’s long history of producing notable bands, from Black Sabbath to Kasabian, and strong culture of gigging wherever you can to hone your chops.

“[Payne] was playing in old people’s homes or singing around, same as what I was doing,” he says. “It’s a work-hard-from-the-bottom-up [mentality] in the Midlands. A lot of our parents — I know Liam’s parents were the same — didn’t come from money. So you’re taught to get out there and earn your crust.”

In 2010, Payne, now 16, returned to The X Factor still sporting the same boyish haircut and singing an American standard (“Cry Me a River,” not the Justin Timberlake one). He won over the crowd and judges with a vocal performance resonating with newfound conviction and dynamism. Upon making it to the next round, Payne, surrounded by his family, said, “My face hurts, I can’t stop smiling.”

Payne, like all of his future bandmates, might not have made it further in the competition had Cowell and Scherzinger not grouped him in One Direction. The quintet jelled quickly to prove themselves to Cowell and the other judges. A rendition of Natalie Imbruglia’s “Torn” earned them a spot in the live finals, after which Payne struggled for words and fought back tears: “I’ve waited a long time for that moment,” he said. “[I’m] absolutely elated, and with these guys, as well, it’s more — it means a lot more.”

Payne’s work ethic was already well-ingrained, but The X Factor presented a new grind. Katie Waissel, a singer who made it to the quarterfinals that season, bonded with Payne and says they became “one another’s rock.” Waissel describes long days beginning at sunrise and ending after midnight. Contestants, she says, were “programmed” to repeat the refrain impressed on them by producers: “We’re just so grateful for the opportunity.” (A rep for Cowell said he was unavailable to speak for this article; reps for Styles, Horan, and Malik declined to comment; Tomlinson’s rep did not respond to a request to speak.)

If you go back and watch the X Factor video diaries One Direction recorded throughout the competition, Waissel says, you can see Payne become “more and more vacant.” She argues the show had a way of transforming a dream job into “a blank space and routine, and that’s not what anybody envisions when they get into music.”

That intensity did not abate after The X Factor. One Direction placed third that season, but even before the finale, the group was becoming a phenomenon. Cowell assured fans that the end of the show was “just the beginning for these boys.”

Payne at the 2010 X Factor finale, where One Direction placed third.

Famous/STAR MAX/IPx/AP Images

‘It’s Like Putting on a Disney Costume Before You Go Onstage’

One Direction were active from 2010 through 2015 — six years of nonstop work during which they released five platinum-certified albums and completed four world tours, playing more than 300 shows in arenas and stadiums around the world. They were the defining boy band of the decade, and are still the only group to have its first four albums debut at Number One on the Billboard 200. By 2020, One Direction had sold more than 200 million records and amassed over 21 billion streams.

Bolstering it all was a legion of devoted fans. The songwriter Savan Kotecha recalled working on 1D’s second album in Stockholm and watching police wade through the crowd camped outside the studio, holding photos of girls reported missing after they’d absconded from home for a chance to meet their idols. Online, too, 1D’s fans formed tight-knit communities, helping to define this new era of social media-driven pop fandom.

For Payne, One Direction was the chance to become the artist he’d always dreamed of being. Shone remembers him as a “workhorse.” Sam Watters, a producer who worked on 1D’s early albums and later Payne’s solo record, says, “You could tell he just wanted to learn how to be a better singer, how to write songs.”

By One Direction’s third album, 2013’s Midnight Memories, all five members were more involved in songwriting, but Payne was particularly prolific. He developed a strong partnership with Tomlinson, and alongside the band’s main collaborators, they wrote large chunks of 1D’s final three albums.

“Singing songs is one thing,” Payne said in One Direction: Our Story, “but when you’ve actually written something, and you hear people in the crowd singing the lyrics, it’s such a buzz.”

Payne’s dedication to the music made him a reliable, responsible group leader — earning him the nickname “Daddy Direction” from his bandmates. “He took it so, so seriously,” Tomlinson said of Payne in the 2013 documentary One Direction: This Is Us. “Whenever I wanted to do anything even slightly mischievous, he was the daddy.”

Eventually, Payne learned to lean into the loose, cheeky, respectfully rowdy aura One Direction cultivated during their peak years. “The more fun we had, the more successful it got,” Payne recalled in 2019. But the fun captured on camera, on record, and onstage was often different from the grueling reality of life in a major band.

“NO ONE TEACHES YOU THAT WHEN YOU GO AFTER FAME, THIS IS WHAT IT COULD LOOK LIKE.”

“From the outside, it always looks like you’re having the time of your life, and often you are,” Shone says. “But the gig represents a very small percentage of the actual experience. A lot of the time you’re shuttled from stage to the hotel and back. You couldn’t get any mental breathing time.… It’s that feeling of being caged up.”

Payne took his first sip of alcohol in 2012. He was 19 and had gotten the OK to drink from his doctor after years of abstaining because of his kidney issues. By his own admission, the “floodgates opened” after that. Within four years, he was recreationally using drugs, according to sources.

In interviews, Payne tied his addictions to his experiences on the road. There was the monotony, euphoria, and bemusement of performing the same show to 60,000 screaming fans night after night. “It’s almost like putting the Disney costume on before you step up onstage,” he said in 2019, “and underneath the Disney costume, I was pissed [drunk] quite a lot of the time, because there was no other way to get your head around what was going on.”

After the shows, he lived within the exhausting confines of planes, buses, and hotel rooms. “The best way to secure us, because of how big we’d got, was just to lock us in our rooms,” Payne said in 2021. “What’s in a room? A mini bar. So, at a certain point, I thought, ‘I’m just going to have a party for one,’ and that seemed to carry on for many years of my life. Then you look back at how long you’ve been drinking and you’re like, ‘Jesus Christ, that’s a long time.’ ”

Payne (in Paris in 2019) said he didn’t know who he was after One Direction.

Helene Pambrun/Paris Match/Contour by Getty Images

Shone recalls a quiet moment with Payne in South America at the start of One Direction’s first stadium tour, in early 2014. He stopped by the singer’s hotel room, maybe to discuss a new song arrangement, and stuck around for a beer. Payne opened up about “how difficult it was being isolated” and the “craziness” surrounding the group. “No one teaches you that when you go after fame, this is what it could look like,” Shone says. “If someone said to you, ‘Here’s a book, open it up, read what fame looks like, see how it feels.… Do you still want to do it?’ No one does that because nobody expects to be famous. They do it for the love of art.”

One Direction released their final album, Made in the A.M., in November 2015, and on Dick Clark’s Rockin’ New Year’s Eve, the now-quartet (Malik had exited the band months prior, citing his desire to be “a normal 22-year-old who is able to relax”) performed live for the last time. For Payne, it was a relief. “The day the band ended, I was like, ‘Thank lord for that,’ ” he said in 2021. “I needed to stop, or it would kill me.”

A Once-Promising Solo Career Falters

As One Direction ended, Payne’s solo career — and adult life — began. In 2016, when he was 23, he started dating Cheryl Cole, 33, the X Factor judge he’d winked at years earlier. Their son, Bear, was born in March 2017, but the relationship wouldn’t survive much more than a year. Two months after Bear’s birth, Payne released “Strip That Down,” featuring Migos rapper Quavo. The song found Payne embracing the R&B and hip-hop sounds he’d always loved but didn’t always fit the pop- and rock-oriented tunes Cowell and others felt best suited 1D. “Strip That Down” cracked the Top 10 in the U.S. and U.K. It was an auspicious start.

But Payne also faced fresh challenges as he adjusted to this new phase. In a 2019 podcast interview, he recalled: “I had no personal life [in One Direction]. I remember getting to therapy one time. When the guy was like, ‘What do you like to do?’ I didn’t know. I just sat there in the chair going, like, ‘What do I actually like to do?’ ”

Payne’s next two singles did well but failed to reach the same heights as “Strip That Down.” Instead of touring, he was doing one-off promotional gigs and TV shows. His addictions worsened. Somers, the sober companion, remembers receiving a call from Payne’s management late in the year with the message: “We need you to go and see this guy. He’s pretty fucked up.”

While Payne’s maturity had defined his early days in One Direction, Somers found a young man “who had never had the chance to fully emotionally mature.” He describes Payne as a “delightful, sweet, lovely boy who, like many people with substance problems, just wanted to be loved.”

“HE HAD A FRANTIC VIBE. IT SEEMED LIKE HE WAS IN A BAD MENTAL STATE.”

Somers helped Payne get sober and accompanied him on the Jingle Ball tour in late 2017. Payne reached a place where he could enjoy social events — golfing, bowling, doing things “somebody his age should be doing,” Somers says. They kept working together after the tour, but Somers says the demands of a pop career posed challenges to Payne’s recovery.

“If you’re an artist like Liam, coming out of One Direction, you haven’t got time to stop and take three years to do the kind of therapeutic work that you might hope for,” Somers says. “You’ve got to move it on.”

After getting clean, Payne’s life brightened when he met a young model, Maya Henry, in 2018 at a fashion show in Lake Como, Italy. Their relationship became serious the following summer, and he proposed marriage in November 2019.

He also set to work on his debut album, recording in studios around the world, working with an array of established hitmakers like Stargate, Ryan Tedder, the Monsters and Strangerz, and Steve Mac. All the while, as Payne put it in 2019, he was “trying to learn to be a person.”

“Liam was damaged prior to becoming famous and had childhood trauma, then was thrown into a brutal cutthroat industry that is notorious for destroying people,” a source close to Henry says. “Achieving fame and wealth at such a young age contributed to his existing problems. As a young boy, he was faced with a sudden shift in responsibility, feeling the weight of financially supporting those around him.”

Payne struck up a creative and personal partnership with songwriter Sam Preston, who, as the frontman of British rock group Ordinary Boys, had band experience. He’d also had his own struggles with substance abuse: In 2017, Preston suffered a near-fatal fall off a balcony in Denmark, which he acknowledges is “fucking insanely, eerily similar” to how Payne died. Preston says he broke nearly every bone in his body, and during his long recovery, he wrote “Live Forever,” about sobriety and that life-changing experience. He pitched the song to Payne, who recorded it for LP1 and eventually released it as a single.

Preston says he and Payne hung out, made music, and, he acknowledges, sometimes drank together. “You could sense there was a real brilliance to him that he was almost afraid of letting people see,” Preston says. “He was such a talented musician, and he could allow himself to be so raw.”

But when LP1 arrived in December 2019, it met tepid reviews and middling commercial success. Because of the pandemic, Payne never properly promoted the album on the road, settling for a string of livestream shows instead.

Preston suggests Payne felt the constant pressure that comes with achieving massive fame when you’re young and forever striving to match or exceed it. “He was like, ‘Well, I have to be the most successful male solo artist, or I’m a failure.’ But that’s an almost impossible task,” Preston says.

There was another pressure, too: All five members of One Direction had gone their separate ways after the split but remained in the spotlight to varying degrees. Malik, Horan, and Styles each went to Number One with their debut albums. Styles’ second album, the multiplatinum, Grammy-nominated Fine Line, dropped one week after LP1.

Ex-fiancée Henry (in 2020) told Rolling Stone, “He hurt me in ways I’ll never fully understand.”

Dan/Will/MEGA/GC Images

“To see his bandmates and have that direct comparison — it’s unavoidable for him to see that all the time,” Preston adds. “And if there was someone who’s prone to addictive, problematic behaviors, then I think that’s just a very difficult situation to be in.”

“Liam said he felt lost when 1D ended,” the source close to Henry says. “When LP1 was not received well, he became depressed and felt his fans did not support him anymore. He had to keep working and making money and expressed his worries about his finances and the pressure to take care of those around him that became accustomed to a certain lifestyle.”

In public, Payne seemed conscious of his career’s shortcomings and was clear about his desire to achieve more as an artist. In 2021, he acknowledged Styles had “found himself” on Fine Line, adding, “I don’t feel like I’ve had that moment within me yet. I’ve written some songs recently that I’m really proud of and happy with, but I don’t feel like I’ve had that moment yet.”

But Payne’s post-LP1 output was scattershot: just three singles, released in 2020, 2021, and 2024, respectively; the last being the potential comeback track “Teardrops,” written with Jamie Scott and ’NSync’s J.C. Chasez. It petered out at Number 85 in the U.K. and failed to ripple the U.S. charts.

On top of his floundering solo career were Payne’s drinking, drug use, and mental-health issues. A source close to Henry says these were “such a burden” that Payne “couldn’t work properly.” Multiple sources suggest Payne also wrestled with his sexual identity, compounding his struggles and leading to risky behavior. “Liam struggled with his sexuality,” a source close to the situation says. “During his relationship with Maya, he sexted men.”

Their romance reached a nadir during Covid lockdowns, when a source says Henry finally grasped the severity of Payne’s addictions after she discovered him using drugs and drinking heavily.

“[Liam] wasn’t recording; he wasn’t touring,” the source adds. “It was like you took someone who had mental-health problems, likely had sexuality issues, already had a drug problem, and then you took away everything that kept him busy — recording, touring, interviews, etc. — and he’s just left with his problems. And then Maya was just kind of held captive. She’s like Ronnie Spector in Phil Spector’s house: She can’t do anything.”

In 2020, Henry learned she was pregnant. According to a source close to Henry, Payne gave her an ultimatum. “Liam sent Maya a long message saying it’s either get an abortion and stay with him, or raise the kid alone and he will not acknowledge either of them,” the source says. “This was a surprise to Maya, because Liam wanted to have a family, and they were trying for a kid.” Ultimately, she agreed to terminate the pregnancy.

After several other disturbing episodes — some of which Henry would later describe in a novel based on their relationship — including instances when Payne allegedly chased Henry with an axe, pushed her down a flight of stairs, and revealed sexting conversations with strangers to her by accidentally broadcasting them to their TV, the couple split in May 2022. “She was just tired,” the source says. “Babysitting [Liam] was exhausting. Maya spent years helping and staying by the side of Liam, who in return wouldn’t get help or seek help for his drug use, violent outbursts, or addictions.”

“ON DRUGS, HE BECAME UNRECOGNIZABLE. I KEPT HOPING EACH INCIDENT WOULD BE A WAKE-UP CALL.”

By the time they broke up, Henry had learned the full extent of Payne’s drug addictions. “It was normal for Liam to do cocaine, ketamine, MDMA, and pharmaceutical pills (Xanax and pain pills),” the source close to Henry says via email. “Then he got into smoking heroin.”

While Henry declined to answer specific questions regarding Payne, she commented on their relationship as a whole in a written statement to Rolling Stone. “This was someone I loved very much,” she wrote. “Initially, it was the drug use and addictions that tore us apart. Anyone who has been with an addict understands how difficult that is. While I loved him deeply, he did things that hurt me in ways I’ll never fully understand, and he continued to hurt me years after we broke up. On drugs, he became someone unrecognizable — so different from his sober self. I kept hoping each incident would be a wake-up call for him to get help, but it never was. I tried to be there for him. I loved him so much that I convinced myself I could fix things.

“I put myself in situations that were unsafe and harmful, ignoring every red flag,” Henry continues. “I knew there were parts of himself he was struggling with — parts of his identity he wasn’t ready to fully face, even within our relationship.… In the end, it wasn’t just the betrayals or the addictions that broke us — it was the realization that I had spent years in something that was never what I thought it was. I don’t fault him for his struggles.”

The source close to Henry says she never reported Payne to the police for his drug use or blowups. “Liam had a lot of deeply personal trauma Maya was aware of that occurred well before he joined [One Direction],” the source says. “When he got violent, the thought was never that he should be sent to jail. He needed help, or to get support from an institution, so he could get to the root of his problems.”

Payne’s private frustrations and addictions erupted into public view in May 2022 when he appeared on Logan Paul’s Impaulsive podcast. Payne sipped whiskey and mouthed off, earning the ire of One Direction fans for making several critical remarks about Malik and airing old band drama (he claimed to have rebuffed an unnamed bandmate during an altercation by saying, “If you don’t remove those hands, there’s a high likelihood you’ll never use them again”). But what seemed to garner the most mockery were Payne’s boasts about his solo career, like the demonstrably untrue claim that “Strip That Down” had “outsold everybody within the band.”

After that, Payne remarked: “How do you go from there? I still don’t know who I am … that’s the worst part of it.”

Amid these chest-puffing antics, Payne revealed himself to be a young man unmoored and grasping for some semblance of identity after more than a decade in the pop machine. Regarding his lack of new music, Payne said he was finding it difficult to write songs that drew on his life, which he described as “vastly confused” for a “boy who’s been locked in a hotel room since he was 15 years old.”

Feigning Happiness in Public, Struggling in Private

Payne flew to Argentina last fall on a routine matter: Foreigners renewing U.S. visas need to leave the States and sit for their renewal interview at a U.S. Embassy or consulate abroad. While people typically return to their home country to do this, Payne chose Buenos Aires, where he could also see his former bandmate Horan in concert.

Payne had a good friend, Rogelio “Roger” Nores, who lived in Argentina, too. They had met at a party in 2020 and become so close that Payne once posted a Snapchat denying rumors that he and the financier were romantically involved. Before his arrival at CasaSur, Payne stayed at an Argentine estate owned by a friend of Nores, a polo enthusiast named Gonzalo Avendaño.

Nores met with Rolling Stone for several interviews in Buenos Aires’ bustling coffee shops in December. At the time, he was still worried about how prosecutors might charge him in connection with Payne’s death, and he spoke carefully, moving between on-the-record and off-the-record conversations. He described sharing a tight personal bond with Payne that never became professional despite all the time they spent together.

Nores, four years older than Payne, characterized their friendship as having something of an odd-couple quality: Nores has never used drugs, he says, and was determined to participate in sober activities with Payne, including hours and hours of bowling when Payne lived in Florida.

“We would both offer a lot of emotional support,” Nores says. “That was the core of our relationship. I was going through a lot of stuff with my girlfriend and family. We’d talk a lot about our relationships and how to go [about] them and how we were feeling.”

Nores, once selected as one of Forbes’ 30 Under 30, has no background in the music industry; he previously supplied capital to build Argentine power plants. The receptionist at the hotel where Payne died, Esteban Grassi, suggested in a statement provided to the Argentine judge overseeing the investigation into Payne’s death that Nores presented himself as Payne’s manager. But Nores maintains that he never held the position nor was he in charge of Payne’s finances. Nores has contested being Payne’s manager in interviews with Rolling Stone and in legal filings. Nevertheless, he was regularly by Payne’s side during the last two weeks of the singer’s life.

“I was his friend,” Nores says. “I wasn’t a doctor, I wasn’t a psychiatrist, I wasn’t his legal guardian. I never had any control of that. I wasn’t his manager; I wasn’t his father. You can only do so much.”

Argentine financier Roger Nores was with Payne often in the singer’s final days.

BACKGRID

Outwardly, when Payne arrived in Argentina on Sept. 30, he seemed like the jolly, winsome former One Direction heartthrob fans knew. He posed for photos with fans and posted Snapchats about how much he adored Cassidy, his girlfriend of two years, whom he’d met at the Charleston, South Carolina, bar where she worked in 2022. Privately, he was still struggling. He’d spent much of 2023 in and out of rehab. His behavior was volatile, sources say — seeking out drugs, sexting fans, and hiring sex workers.

Nores, in his own written statement provided to the judge, claimed Payne’s addictions hit a new low in 2023, including a “severe overdose” that left him “close to death.” That same year, Payne and Cassidy split briefly. Henry, with whom he’d stayed in touch, saw him smoking a substance, possibly crack, during a FaceTime call, according to a source. That December, the source claims, Payne sent Henry graphic images of himself and an “intimate photo” of Henry taken during their engagement that she thought he’d deleted. “She emailed him and let him know the distribution of intimate photos without permission was criminal and to delete the pictures,” the source says.

By 2024, Payne was in a fragile state. In March, the same month he released “Teardrops,” he entered rehab in Spain but left without completing the program. In April, Nores wrote in his statement, Payne relapsed again and was hospitalized “in serious condition, with professionals having to resort to resuscitation maneuvers in order to save his life. His father unsuccessfully tried to commit him to a psychiatric treatment center, which Payne opposed.” Payne went through even more treatment programs without completing them. In the midst of it all, Payne’s U.S. label, Universal Republic, dropped him.

What could have been a career comeback for Payne faltered when he failed to promote “Teardrops.” “Several key promo opportunities — major interviews, performances, launch events, content days, and fan events — were canceled, offers ignored, or major partner commitments unfulfilled,” a source close to the situation says. Moreover, his label reps worried about Payne’s well-being. When, a few months later, it was suggested to the label that Payne tour South America, the reps balked. He was in no shape to go on the road. “It was decided by the label, given these factors combined with concerns for his health, to terminate the working relationship rather than further release music,” says the source.The split from Universal Republic was legally formalized by September.

But there was one period last year when the chaos around Payne seemed to subside. In early summer, Payne spent several weeks living at another property owned by Nores’ friend Avendaño, a polo club in Wellington, Florida, outside of Miami. During his stay, sources say, Payne appeared to be sober.

Avendaño recalls how Payne spent his days drawing and writing songs. He took one video of Payne at a keyboard playing a gentle R&B track reminiscent of the Commodores’ “Easy,” and another of a more upbeat tune. Avendaño even suggested polo as a positive activity to help Payne’s mental health. He has photos of Payne on horseback with a polo helmet and stick.

“Liam was playing polo and looked good,” Payne’s father Geoff recalled in a witness statement provided to Argentine prosecutors.

But Payne was still consumed by his demons. Avendaño says the singer would talk about drinking a bottle of whiskey on performance nights with One Direction, and how the band would evade chaperones by leaving hotels via balconies to party.

“When he was prisoner of his anxiety, he would stop you and ask you, ‘Do you have a phone number for a drug dealer around here?’ ” Avendaño says. “And I said, ‘No, Liam. No, no, no. I have no idea.’ He’d say, ‘OK, OK, OK.’ ”

Avendaño says Payne also ruminated on his romantic relationships: He wished he could reconcile with Cole, and worried that Cassidy’s spending habits were out of control. (Nores also claims in court records that Payne was financially supporting Cassidy. She could not be reached for comment.)

It was during this time that Geoff Payne said he started placing trust in Nores. “Roger, in that moment, voluntarily, offered to be in charge of Liam,” Geoff said in his witness statement. Nores, Geoff claimed, was a frequent conduit between father and son. When Liam died, Geoff wrote, it was Nores who informed him.

Nores, for his part, has always maintained that he was only ever Payne’s friend. A defamation lawsuit he filed against Geoff in Florida in January reads “[Nores] never agreed to be and was never the caretaker of Liam. [Nores] did not have a legal duty to Liam. Liam and [Nores] were dear friends and provided each other ‘friend support.’ ”

The source close to Henry says that in early May 2024, Nores contacted Henry, asking for advice on helping Payne with his addictions and his career. “The offer seemed genuine, and she knew Roger was trying to help, but there was something unsettling about it,” the source says. “She had been trying — and failing — for years to get Liam the help he needed. Roger didn’t seem to understand the complexity of Liam’s struggles.… Liam could go months sober, only to relapse, and it wasn’t about staying clean. He needed to face the root cause of why he used drugs in the first place.” (Nores declined to comment on this claim.)

In July, Payne signed a new contract with talent agents at CAA “for all areas of representation,” according to Billboard. The following month, Payne flew to Manchester, England, and served as a guest judge on the Netflix reality-TV music competition Building the Band. Crew members say Payne was affable and upbeat on set, and even hung out at the wrap party, unusual behavior for a star. “He remembered people’s names and was chatty and approachable,” Simon Hay, the show’s shooting producer-director, says. Another crew member recalls Payne as “egalitarian and charming” and said he “really wanted to help” the eliminated contestants. “That was the extra gut punch when I heard the terrible news,” the source says. “He wouldn’t be able to help them anymore.”

Backstreet Boys’ AJ McLean, a fellow judge, who has had his own struggles with addiction, recalled Payne appearing sober on set. “He and I immediately connected on not only a music level but a human level,” McLean says, “like we both were living a parallel life. There was a lot of funny boy-band jabs that we would take at each other. He really had a quick wit to him — that nice, dry, British humor.”

Payne told fans on Snapchat he was enjoying his Buenos Aires trip in the days before his death.

In a September Snapchat video announcing his and Cassidy’s plans to visit Argentina, Payne said he was looking forward to attending Horan’s Buenos Aires concert on Oct. 2. “It’s been a while since me and Niall have spoken,” he said. “[We] got a lot to talk about, and I would like to square up a couple things with the boy. No bad vibes or anything like that, but, just, um, we need to talk.” (Nores says, “They met, and Liam was happy.”)

The day after Horan’s concert, Payne went to the U.S. Embassy for his visa appointment. What should have been an easy task hit a speed bump, Nores said in his statement, when the authorities insisted an Argentine psychiatrist evaluate Payne because he had been to several rehab centers throughout the years. The decision was a matter of policy, but it created a ripple effect that kept Payne in Argentina for the next two weeks.

Payne met with a doctor on Oct. 6 or 7, according to Nores’ statement, “for a clinic visit and drug analysis (including blood work and X-rays).” Nores wrote that the doctor said nothing “as far as I know” about Payne requiring medical attention. (Rolling Stone was unable to reach the embassy to confirm Nores’ account.)

At the same time, allegations of Payne’s disturbing behavior started becoming public. On Oct. 6., in a TikTok, Henry claimed the singer had been harassing her and her family. “Ever since we broke up, he messages me, will blow up my phone,” she said, alleging Payne used multiple phone numbers and iCloud accounts to message her.

Payne’s behavior was apparently even scarier than what Henry let on. In a cease-and-desist letter, reviewed by Rolling Stone, which Henry’s lawyers sent to Payne and his agents at CAA on Oct. 9, Henry reported receiving concerning messages from a stranger about Payne’s behavior. “[Liam] started blowing up my phone very recently on an iCloud email, and when I asked who it was, he started asking me if I wanted nudes of you/his current gf,” the woman informed Henry, as seen in screenshots of messages included in the cease-and-desist letter. “I said absolutely not.”

Other screenshots included a sexual image, ostensibly of Payne, that Henry’s lawyers censored and messages from an email address known to be Payne’s with a vulgar request: “Send me fucking and sucking vids. Did I ever send u ones of Maya? Or any of my exes.”

It didn’t end there. The letter alleged that Payne had “sent unsolicited and disturbing images and videos” to Henry and her family, including “pictures of his genitals and various videos of Mr. Payne performing disturbing sexual acts on himself.”

“HE IS IN A ROOM WITH A BALCONY, AND WE’RE A LITTLE AFRAID.”

“[Henry’s] goal wasn’t financial compensation — she wasn’t seeking money,” the source close to Henry says. “Instead, she wanted to force Liam into a rehabilitation program, requiring him to undergo six months of intensive treatment followed by a monitored aftercare plan.… It was about holding Liam accountable for his criminal actions and ensuring he received the help he so desperately needed.”

When Payne’s father, Geoff — who had flown to Florida to check on his son between rehab stints earlier in the year — learned about the cease-and-desist letter, he worried about how his son was processing Henry’s accusations. “I understand that [the allegations] really affected him emotionally, even if Roger and his girlfriend [Cassidy] told me he was fine,” Geoff wrote in his witness statement. “I understand that they didn’t speak about it much with Liam because he was very closed off about personal issues.”

A conflict between Henry and Payne had been brewing for months. In May, Henry published Looking Forward, her roman à clef about her engagement to Payne. In the book, she describes an abusive relationship between a naive model named Mallory and a singer named Oliver Smith, a former member of a fictional boy band called 5Forward.

“It was written as a memoir, basically,” the source close to Henry says. “But then she made little changes throughout for creative reasons. Some of the dialogue is fake.”

In Looking Forward, the pop star, Oliver, takes cocaine, MDMA, and pills, sexts other women, and threatens suicide if Mallory were to leave him. “There was one time, while under the influence, Liam tried to leap off the top of his penthouse balcony [and] Maya had to stop him,” the source says of an incident in the book that was apparently based on a real experience. In another scene, Oliver shoves Mallory, breaks a light fixture, and chases her with an axe. She calls his manager, who tells her to leave him, but she doesn’t. After an incident where the pop star snorts coke in front of the girl’s mother and grandmother (the source confirms this was real, adding that a young cousin was also present), she works up the courage to leave him.

As shocking as the allegations are, Henry may have left the worst of them off the page, with the source adding that Payne would “just flip a switch when he was high on drugs.” “There are certain things that she still feels like she’s processing,” the source says. “It’s one thing to talk about how your fiancé texted your mom his dick pic, which did happen; it’s another thing to deal with some of this abuse stuff and talk about that publicly.”

“I stood by him in his darkest moments, through the chaos, through the pain, through things that broke me in ways I can’t explain,” Henry said in her statement to Rolling Stone. “And yet, when it was all over, I was left with nothing but emptiness. The love I gave, the sacrifices I made — they weren’t enough because they never could be. I wasn’t just heartbroken; I felt defrauded, as so many women in my position would. But what I do know is this: It wasn’t about me or anything I did. It was about struggles beyond my control. And in the end, I had to choose myself. I had to walk away, no matter how much it hurt, because staying in his world meant losing myself.”

Even though the novel recounts horrific personal details from Payne’s and Henry’s engagement, Nores claims that Payne didn’t seem bothered by it. “He mentioned it once, but he wasn’t concerned at all,” he insists.

A few weeks after Payne’s death, Henry discovered even more alleged instances of his distributing intimate photos taken during their time together, according to a source. One of Payne’s friends reached out to her, the source says, and “revealed that Liam had been sharing the intimate photos with them and others for a long time — well beyond what Maya had initially realized, even dating back to their engagement.” The source says Henry views Payne’s actions “not just [as] a betrayal but a criminal act” and hired lawyers in the U.K. to seek legal remedies.

“After everything, what hurts the most is that even after his death, I’m left with the aftermath of his actions that continue to unfold,” Henry said in her statement. “As I’ve uncovered the extent of his nonconsensual image sharing … I’m faced with the complexity of grieving for someone I cared so deeply about despite the pain they have caused me.”

Payne’s patterns continued into his new relationship. Sources say in early 2024, after Cassidy caught Payne sexting other women, she revoked his phone access, forcing him to use his laptop as a means of communication.

“I stuck with Liam through thick and thin,” Cassidy said in a February interview with The Sun. “And I think love is so optimistic. You just hope everything at the end will work out.”

On Oct. 12, two weeks after Payne and Cassidy arrived together in Buenos Aires, she left. In a video posted to TikTok that showed people packing her bags into a car, Cassidy said she’d grown homesick: “We were supposed to be there for, like, five days [but] it turned into two weeks, and I was just like, ‘I need to go home.’ ”

“They had a happy goodbye,” Nores says. “He wanted to marry her. Two days before he died, he asked me if I wanted to be his best man.” “If I could see into the future, I would have never left Argentina,” Cassidy told The Sun. “When I left Argentina, we had such a great day, and he was in such a good headspace. We were just full of love, and I never would have expected [his death] to occur.”

‘You Could Tell on His Face That Liam Was Unwell’

Years ago, the district of Palermo, where the CasaSur stands, appealed to Argentine film producers for its cheap studio space and ample parking. People started calling the neighborhood Hollywood. There are small parks, boutiques, mom-and-pop shops, and plenty of cafes. Local TV stars still frequent the area, but if you ask anyone, they’ll tell you it’s unusual for celebridades internacionales like Payne to stay at the boutique hotel.

Shortly after his arrival there, prosecutors now allege, Payne recruited a CasaSur employee to retrieve drugs for him. Payne also met up with Braian Paiz, a waiter at a nearby restaurant, whom he messaged at close to two in the morning on Oct. 14, according to screenshots Paiz posted to Instagram. “You around? What’s your number,” Payne asks.

“We took drugs together, but I never took drugs to him or accepted any money,” Paiz told Argentine news outlet Telefe Noticias in November. They “spent the night together,” he said. “We consumed drugs because the truth is that something intimate happened.” Later, Paiz denied having sex with Payne.

The morning after his rendezvous with Paiz, Payne refused to see Nores. Instead, he “wanted to be alone,” according to Nores’ statement. Later, Nores went with Payne to take a visa photo. When they saw each other that night, Nores wrote, Payne’s room contained no “traces of narcotic consumption.” An employee of the sushi spot where Nores and Payne dined tells Rolling Stone, “You could tell on his face that Liam was unwell.”

At 9:45 in the morning on Oct. 16, the day Payne died, he messaged a sex worker he found online: “Wanna play? I have all day. I’d gift you $5,000 US dollars. You come to my hotel.” He then asked if her friend would join.

While he waited, Payne met Nores for a bite at Sacro, the restaurant connected to the hotel. Payne ordered a whiskey. In his statement, Nores says he protested, but Payne drank it anyway. The singer had his laptop with him and said he was working on music. He was also messaging friends: Scherzinger, Avendaño, and Jodie Richards, a performance coach from Payne’s youth, all reported hearing from him that day. Richards said that Payne seemed upbeat.

Nores and Payne went up to the singer’s room, where Nores “personally did not detect the presence of drugs or signs of consumption,” as he wrote in his statement to the judge. Nores left shortly before 11 a.m., and the women Payne had invited arrived half an hour later with alcohol for him.

By 2 p.m., Payne had refused to pay the sex workers. The women complained to the hotel staff, and the receptionist called Nores, who said it wasn’t his problem. Still, he headed to the hotel. At 3:30 or 4 p.m., according to prosecutors, Payne bought cocaine from a hotel employee, and the sex workers left.

Around this time, Nores saw the mess in Payne’s room. Photos from the scene taken after Payne’s death show a shattered TV with a spider’s web of cracks and drug paraphernalia like white powder, aluminum foil, and a makeshift pipe. Nores “expressed his displeasure” with Payne for breaking the TV, he wrote in his statement. They said goodbye around 4:15 p.m., after Payne said he was going to meet a friend, whom Nores believed was another hotel guest Payne had met in the lobby. Instead, Payne had the breakdown Watson, the groom staying a couple of floors below, witnessed.

A smashed TV in Payne’s room.

Over the next 45 excruciating minutes, Payne’s behavior worried hotel staff to the point that they kept five staffers standing watch outside his door. They left around 5:03, according to Nores’ statement, based on security footage allegedly reviewed by his legal team.

“I never imagined that he would die,” says Salinas, the masseur who helped move Payne from the lobby. “If I had known [Payne’s] room was destroyed, I would’ve told them to keep him in the lobby and keep him restrained.”

CasaSur receptionist Grassi, who declined to comment for this article, called 911 twice around 5 o’clock. “We need you to send someone urgently because, well, I don’t know whether his life may be in danger,” he said in his first call, requesting medical help but urging against a police presence. “He is in a room with a balcony, and well, we’re a little afraid…” On his second call, he asked for medical assistance. Help arrived too late.

Laying Blame and Digging for the Truth

Throughout December, prosecutors compiled a criminal case to hold those who might have contributed to Payne’s death accountable. On Dec. 27, they indicted five people. Hotel employee Ezequiel Pereyra and Paiz were accused of supplying Payne drugs; and Nores, Grassi, and CasaSur Palermo manager Gilda Martin were charged with homicidio culposo, which is similar to involuntary manslaughter in U.S. court.

All five have maintained their innocence. A lawyer for Paiz denied the allegations, saying, “[They’re] looking for guilty parties and accusing innocent people of committing crimes.” Pereyra’s lawyer denies his client ever supplied Payne with drugs and calls him “completely innocent.” And while Martin, Grassi, and Nores remain free, Pereyra and Paiz were taken into custody and ordered to be held on preventive detention because of the severity of the charges against them. (Both face four to 15 years in prison if convicted; the charges against Nores, Martin, and Grassi carry a possible sentence of one to five years.)

Judge Laura Bruniard of Buenos Aires’ criminal court ultimately ruled that there was enough evidence for the cases to go to trial. At press time, an appeal hearing was scheduled for Feb. 11. It could be months, if not years, before there’s a final resolution.

Judge Bruniard ruled that Payne was trying to “leave from the balcony” of his hotel room when he fell. Although the judge acknowledged that Payne’s intoxicated state may have contributed to the tragedy, she was not swayed by theories that Payne had fainted, jumped, or lost his balance before his fall. She nevertheless suggested that those indicted bear some criminal culpability.

“I do not believe that [Martin, Grassi, or Nores] planned and wanted Payne’s death … but created a legally disapproved risk,” she wrote. Martin and Grassi, the judge added, were “imprudent” in allowing Payne to be taken to his room and left alone.

A source close to the Buenos Aires prosecutor adds, “[Martin and Grassi] knew for two or three days that he was breaking things, consuming [drugs and alcohol]. It wasn’t hidden.”

Grassi denies guilt. “I was not responsible for Liam Payne’s personal care, neither legally nor within the contractual framework of the hotel service provided by my employer,” he wrote in the statement he gave to the judge. Grassi also said that, in his opinion, Nores was far more responsible for the singer: He referred to Nores as Payne’s manager and alleged that Nores reserved Payne’s room at CasaSur on his credit card.

A surface in Payne’s hotel room covered in apparent drug paraphernalia.

The judge, meanwhile, described Nores as Payne’s “guarantor.” She wrote that when Nores last saw Payne at the hotel, approximately 50 minutes before his death, Nores should have seen that Payne was intoxicated and vulnerable.

Prosecutors initially sought to charge Nores with the more serious “abandonment of a person followed by death,” as well as the “supply and facilitation of narcotics.” The abandonment charge was eventually downgraded to negligence, and the drug charge was dropped.

Nores vociferously denies helping Payne acquire drugs. “Of course, I never gave him money for drugs,” he says. “I never gave him drugs. I don’t drink alcohol, and I’ve never interacted with a dealer in my life.”

Still, Geoff Payne casts blame on Nores, claiming in his witness statement that his son’s friend “broke the format of care” in Buenos Aires when he booked Payne his own hotel room after Cassidy’s departure. “That’s how this all happened,” Geoff stated. “Roger knew that the objective of the group was to keep Liam busy,” he wrote, defining “the group” as Nores, Cassidy, and Payne’s bodyguard, whom Payne had fired at the end of the summer. “You couldn’t leave him in a vulnerable situation.”

In early January, Nores filed a civil suit in a Florida federal court accusing Geoff of making false and defamatory statements to Argentine prosecutors. Payne’s estate denied the allegation on Geoff’s behalf.

Ultimately, Nores suggests, Payne was responsible for himself. “He was a fucking free person,” Nores says. “He did whatever the fuck he wanted. Nobody would stop him.”

‘I Asked Him to Promise Me That We’d Both Be OK’

In early December, two months after Payne’s death, the lobby of the CasaSur Palermo is filled with a flurry of holiday activity. The staff is gathered for a photo shoot donning Santa hats and glasses while Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas Is You” plays. Upstairs, the mood is more subdued. The hotel’s halls are dark and dimly lit — black walls broken up by black doors, room numbers embossed in gold. In front of room 310, a security guard sits in a chair.

Right outside the hotel is a memorial to Payne that a few dedicated fans have tended to daily. Carnations and roses in white, purple, and pink, and a few big sunflowers sit at the base of a tree. Covering the trunk and the surrounding planter are photos, signs, and handwritten notes.

“How can I forget someone who gave me so much to remember?” reads one, quoting Payne’s song, “Remember.”

“Your memory will stay alive until my heart stops beating,” goes another.

On Dec. 11, some of the fans who tend to the memorial gathered outside the prosecutor’s office in Buenos Aires — an effort to show officials that “we’re following the case closely,” explains organizer Luana Bustamente, 26. The following weekend, on Dec. 14, two days before the two-month anniversary of Payne’s death, a group of 30 meets at the Plaza Libertad and marches to the nearby courthouse, chanting, “¡Justicia por Liam! ¡Justicia por Liam!”

“It’s important to fight against this injustice,” Karla Reyes, 20, says. “He deserved a longer, more successful life. He deserved to see his son grow up.” She adds: “I think this can actually make a difference. I hope they see us. If there’s more [rallies], I will be here supporting.”

Reyes says she met Payne outside of a different Buenos Aires hotel last October, waiting almost two hours to say hello as the singer signed autographs and took photos with fans. “It was the best day of my life,” she says, smiling.

She’d been a casual fan of One Direction but was drawn to Payne during his solo career in part because of his willingness to speak openly about his struggles with addiction and mental health. Payne’s song “Live Forever” — the one Sam Preston wrote about his own substance abuse issues and near-fatal fall — had a special resonance, Reyes says, assuaging her during her own bouts with anxiety and depression. “His music helped me when I needed him most.”

Reyes says she was nervous meeting one of her heroes, but when she spoke with Payne, he offered compassion and comfort. On a piece of paper, he drew her an arrow — like the ones tattooed on his right arm — and Reyes has since tattooed the drawing onto her own wrist. She carries his laminated autograph wherever she goes.

“I asked him to promise me that we’d both be OK,” Reyes remembers. “He had all the patience in the world and said, ‘Yes, we’ll both be OK. Everything will be OK.’ ”

Leave a Comment