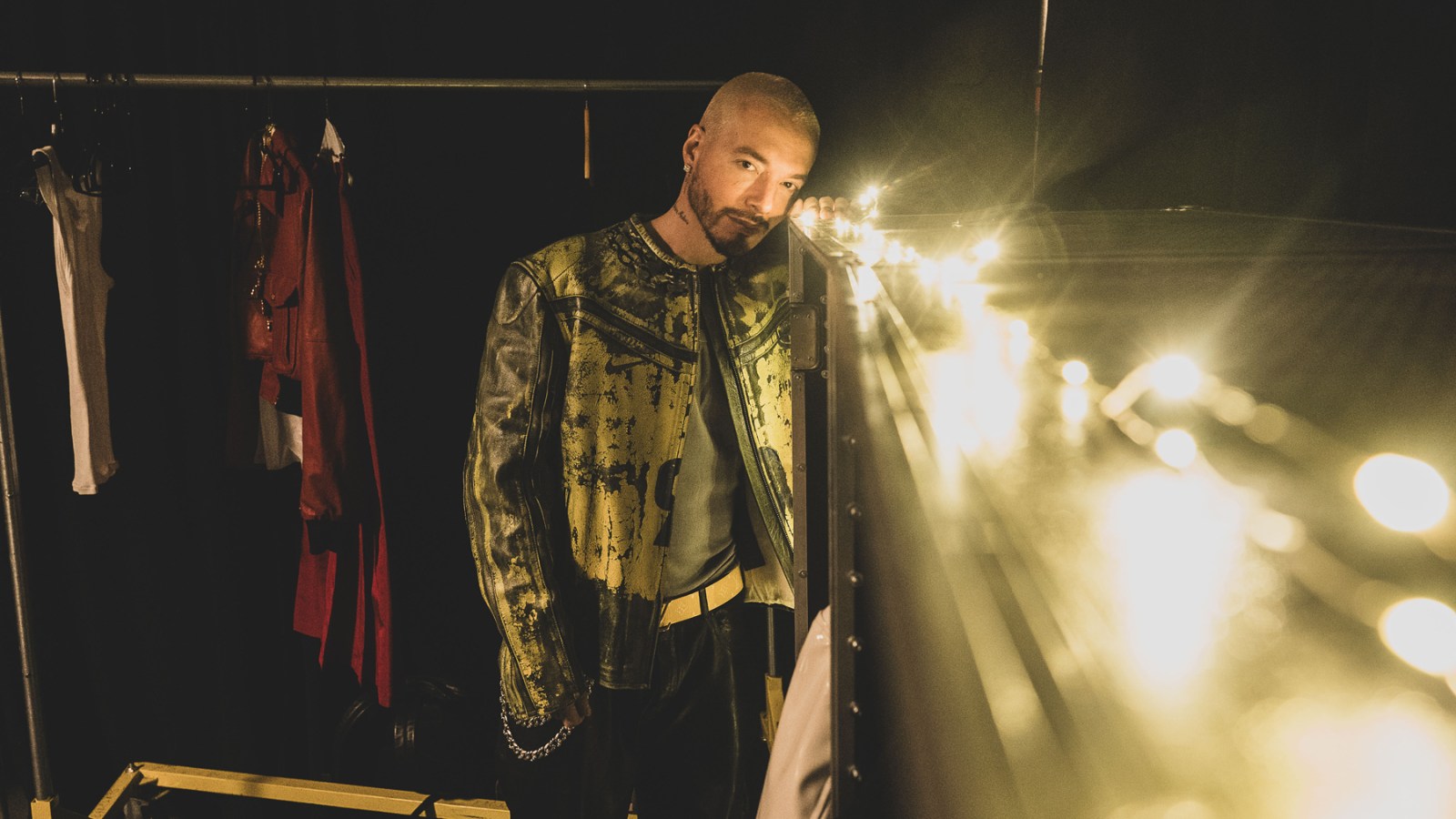

At 40, J Balvin has nothing left to prove — he already has iconic albums like 2018’s Vibras and 2010’s Colores under his belt. Still, earlier this month, a few days after performing at the halftime show of the FIFA Club World Cup final in New Jersey, the Colombian star dropped Mixteip, a breezy, playful collection that appears specifically designed to soundtrack the last weeks of summer.

Unlike last year’s Rayo, which overflowed with high-profile features, the more concise Mixteip moves at a casual pace. Balvin casts a nostalgic glance at the classic reggaeton beat that fuels most of these tracks. He collaborates with British rapper Stormzy, then detours lovingly into traditional merengue and salsa with Omega and Gilberto Santa Rosa as sympathetic allies. Put together, the 10 songs suggest a return to the roots, as if the singer was craving to reconnect with the primal sounds that inspired him when he was first emerging as a global star — or dreaming of becoming one.

Balvín spoke with Rolling Stone about his love affair with New York, his multi-disciplinary approach, and the post-traumatic feelings of a certain Bizarrap session that placed him in the eye of the storm a couple of years ago.

Before we talk about Mixteip, I want to touch on your 2020 single “Rojo.” In retrospect, it was one of the key tracks that heralded the new, progressive sound of Latin music in the 2020s. I thought of Paris in the late 19th century, when the old school “Rojo” is a moment in color – a feeling, a fleeting impression. Do you agree?

100 percent. I wanted to bring something entirely different to the game, add a new element that would make me stand out. But you’re never going to be different just by trying to be different. In the end, the key to making my mark was staying true to myself. “Rojo” is one of my favorite songs to perform in concert, because it signified a before-and-after. If you think about it, it’s like a modern balada. I know many American rappers who are rough on the outside, and yet they tell me that “Rojo” is their favorite song. When we recorded it, the emotion behind it was stronger than anything else. The vibration of that particular moment was in sync with the song’s message and the pitch of my voice.

The opening track of Mixteip, “Bruz Wein” has the trademark J Balvin feel: a gauzy, sweet cloud, a mood of instant intimacy. How do you generate that?

From “Rojo” to “Bruz Wein” [Smiles]. It was nighttime in New York, and the Empire State Building looked cloudy in the distance. I asked for the lights at the recording studio to be dimmed, so that we could see the reflection of the city through the windows. I felt in a cloud myself, thinking about Bruce Wayne embarking on a journey. It was the feeling of New York, of going for nightly walks, which is something I do. I love the moments of solitude, wearing my hoodie, listening to music or calling my friends on the phone. When you are performing live, you’re Batman. After the show, your wife is at home waiting for Bruce Wayne.

There is a personal mission behind my music: for us Latinos to finally be allowed to step outside of the box. “You speak Spanish, this is the kind of art you are supposed to make, this is what you are allowed to give.” I never understood why nobody had done anything about it. We deserve our rightful place as citizens of the world. It was a long road, from gaining respect in the business, to telling my stories with visuals, and expressing myself through every possible avenue. Fashion, for instance, is a way of singing without using melodies. Collaborating with [Japanese artist] Takashi Murakami allowed me to educate the younger generations on the kind of art that I love but not too many people know about. I don’t need a marketing team to teach me how to express my ideas.

Listening to Mixteip, I started thinking, “What makes a mixtape a mixtape?”

A mixtape is a herd of ideas. A collection of songs that I kept locked in my wardrobe until I felt that I would go mad if I didn’t release them to the world. Mixteip is about freeing all those sequestered songs. They deserved to be out there. None of this was planned. Otherwise, it would be another album where I’m telling you a story. There is a random factor to these 10 songs. You could play them in any order you wanted, and the story would remain unchanged.

Many of the tracks have the old-school reggaeton beat, as if you were feeling nostalgic for the reggaeton that was.

Because the entire project was unplanned, I ended up connecting deeply with the old J Balvin that people loved — my more melodic, romantic side. Yes, there was some nostalgia for those early reggaeton songs, and I felt comfortable in that world. At the end of the day, music is all about the vibes.

“Misterio” may be the record’s most epic track. It begins in urbano mode, but morphs into salsa, with Gilberto Santa Rosa on vocals. It’s organic salsa, heavy on the trombones. Was that planned?

Nothing was planned [Laughs.] Originally, the entire song was reggaeton, but then we started talking about the melody, and it had a hint of salsa in it. I was talking with Daddy Yankee’s son, Jeremy Ayala, who’s a great producer, and with J Castle, another fantastic producer. There was silence in the room, and then the name of Gilberto came up. We all agreed that he’s our favorite living salsa singer.

He is such an icon. And salsa is such a vital component of Colombia’s musical DNA.

For me, this duet is as important as recording with Beyoncé. I grew up listening to Héctor Lavoe, the Fania records, Tito Rojas, Tito Nieves — there are so many great salseros. I was 14 when I learned how to sing Gilberto’s “Perdón” — the live version, from the Carnegie Hall album. If Gilberto had turned us down, “Misterio” would have stayed as a straight-ahead reggaeton.

Colombian groups like Fruko y sus Tesos and Grupo Niche brought a touch of honey to tropical music, with all those sweet choruses and minor key melodies. The same could be said about the contribution of artists like you and Karol Go reggaeton.

I think we brought a lot of light at a time when reggaeton was in a dark place, not only sonically, but in terms of the industry. Emerging from a place like Medellín, that at one point was considered to be the most dangerous city in the world, the least we could bring to the table was some joy and positivity. So we brought light, and hope, good vibes and sweetness. At the precise time when there was a need for a different color, we arrived.

For many, Residente’s 2022 session with Bizarrap was unacceptable. What was it like having that directed at you publicly? Iis there an antidote for that?

I remember talking with my mother at the time, and she told me, “Now you know what human misery is all about.” I believe the most important task was to forgive myself for all the feelings of anger, hate, and betrayal that I experienced. Hate is a poison consumed only by the person who’s feeling it. Forgiveness is the antidote. In time, I think people began to realize what was and was not true about all that narrative. And if they don’t, I won’t lose sleep over it, because I happen to know exactly what my truth is.