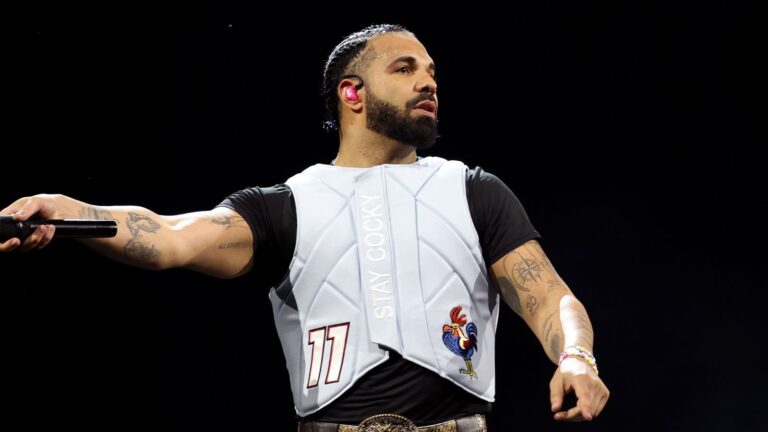

For the past few years, Adrian Quesada of Black Pumas fame has injected new life into the 19th-century bolero. Inspired by the traditional Latin American ballad and psychedelic recordings of the Sixties and Seventies, Quesada is among the many artists and producers that are casting the genre in a new light, subverting the archetype of the weeping, lovelorn woman, and reimagining the vintage sounds without shedding its emotional core.

Quesada first did this with Boleros Psicodélicos, his 2022 album that drew him attention and critical acclaim. “Traditional boleros are recorded in a very organic, natural way. And psychedelic music is heavy on vibe and heavy on attitude and cool sounds, but they’re not always really good songs,” he explains. “When you combine those two, that’s what makes my head explode.”

For the second installment of his Boleros Psicodélicos, Quesada spoke to Rolling Stone about his collaboration with artists like iLe, Ed Maverick, and Monsieur Periné, the songs he obsessively returns to, the bolero as a type of lingua franca, and the tradition of reinterpreting songs, beyond the trappings of nostalgia.

Boleros Psicodélicos was released to considerable acclaim. How did your creative process evolve when making this follow-up album, and what criteria guided you this time around?

The first thing that was different right away with this one was that the first one was done during the pandemic. So it was all done remotely — I was never in the same room with anybody. And it was really cool. I love it and I’m proud of it and this wasn’t anything that I noticed, but somebody pointed out to me that it has this feeling of isolation. So maybe that’s really heady to project onto it. I wanted this one to feel more intimate and really feel like we were in the room together. So the instrumentals were recorded that with a live band in the room all at once and then made some changes later, but for the most part that all of it was started and then whenever possible with the collaborators, the singers and the other artists that were on there, I wanted to be in the studio with them.

I wanted to have a more intimate collaboration with them and have changes made in real time and ideas exchanged. I wanted the artists to really, you know push me and bring ideas to the table that I maybe wouldn’t have brought. And then the last step was that I brought in a co-producer towards the end — a guy named Alex Goose out of L.A. and so he was like this other third layer to it all where I basically then handed him everything and asked, “What would you do here? Go crazy and change everything!” So it was a lot more letting go and trusting other people.

All of the artists are people that I’m fans of. They’re not all necessarily “bolero singers,” nor are all the songs really even boleros on the album. But they’re just all people that I’m a fan of. I think there is a certain style that you do have to work with this kind of music. But it doesn’t necessarily have to be like in the style of boleros. I do think they all have a kind of adventurous fearlessness to their work that I’m really attracted to.

Both Boleros Psicodélicos have come out at a time in which other artists such as Xenia Rubinos and Kali Uchis were also pulling from this musical and lyrical form. To what do you attribute the resurgence of the bolero in the musical imagination?

I think we’ve seen so many trends come and go with music and I’m well past the age of trendy stuff at this point. So you see those trends come and go but there’s a reason that this song form has been around for 100 years or whatever. I think it’s timeless and people keep coming back to stuff like that and cycles through every few years. What really started this idea for me, which was probably almost 20 years ago at this point, was more in line with the era of what they call balada — late Sixties, early Seventies.

[Growing up] there were boleros around me, for sure. But I was listening to hip hop and punk rock and rock and roll. Still, boleros were everywhere. You know how it is: You just grow up around it and you know those songs. But the thing that really sparked it all for me was more when you get to this era where bands were influenced by popular music, by psychedelic music, and soul music . And they’re now interpreting these songs that are boleros, but in that style. That’s what fascinated me the most and that’s what got me way into it because I love boleros and I love psychedelic music. I’m a producer, so I like sounds. Traditional boleros are recorded in a very organic, natural way. And psychedelic music is heavy on vibe and heavy on attitude and cool sounds, but they’re not always really good songs. When you combine those two, that’s what makes my head explode.

When I heard Los Pasteles Verdes for the first time, I was like, “Oh my God, this is like the most out there sounding thing.” So I think there’s a resurgence for sure in the bolero where my interest falls in all of it more in that era.

There is an emotional dynamism and an excess of feeling that is inherent to boleros, often portrayed as a form of lovelorn desperation. How do you modulate emotions in these renderings? What do you seek to highlight or obscure?

Because I don’t sing and I don’t write lyrics, I try to make the music as emotive as possible. I listen to a lot of instrumental music. What I love about music that doesn’t have words is that you can close your eyes and imagine something. And I always try to make my music before it even gets to the singer. Or the vocalist or the collaborator. Before that, I try to make it so emotive that you could listen to it on its own. Obviously, with this style of music…it’s a little bit dramatic. I wouldn’t say it’s understated.

In terms of what the collaborators, particularly the singers, did. I honestly didn’t really give anybody any ideas for lyrics because I really love people’s take on what they wanna bring to it, you know, even with a cover like the song that iLe does. You know, iLe’s whole thing is reclaiming [the form] and not always making it into the story of the damsel in distress suffering from heartbreak. And, you have stuff like what Ed Maverick is singing about is on some other existential level. So I love that what people are singing about is not so on the nose or cliche. Of course, we’re also doing some covers where there are just songs about heartbreak or loss. And some people did sing about that, but I love that whenever possible, we kind of push the boundaries. It’s kind of like they say about hip hop: It didn’t invent anything, it reinvented everything. I can’t say I’ve invented any of this but I can ask, “How do we reinvent it and how do we push it forward?”

Boleros date back to the 19th century and have since traversed many regions across Latin America and the Caribbean. Whether groovy or stripped down, or even accompanied by a Mexican trío, boleros possess a sound that seems saturated with gilded, timeless qualities. How do you view the inherent nostalgia in these songs and their various interpretations?

That’s a good question. I don’t really know the answer to why I’m attracted to this music. I know that I necessarily feel nostalgia when I listen to it. I’ve listened to a song. Twenty times in a row the last like five nights since I’ve been here in London, a song from the early Seventies, by French artist named Michelle Fugaine called “Une belle histoire.” He originally recorded it in French and it was such a hit that he recorded it in Spanish. So there’s like all these really cool versions of that song out there that people ended up making it in Spanish, even though it was originally a French song, but I just found all these other versions and I’ve been listening to that song and it’s from like, I think it was written in like 1971 or 1973 or something and that’s just the song I want to listen to before I go to sleep.

[The song] sounds like a bolero.It has the same kinda chord progression. Maybe a little bit more out there French version lyrics of a Bolero. It’s just a beautiful song. The original version that my friend turned me on to was a Spanish version from I believe the band was Las Cuatro Monedas, from Venezuela. And then from there I just listened to that version over and over and then I found the original and then found the French version and then also I have like eight versions of that song on vinyl.

I just love [these] songs. Maybe I’m stuck in the past and that’s the problem. I have heard people making new Bolero music and really trying to make it retro and kind of trying to be kind of cheeky with it. It doesn’t seem to me like I’m trying to do something vintage. This is just what I like to listen to.

I’m personally fascinated with covers. Much like American folk music, there have been plenty of Spanish-language songs across genres that have been re-recorded, re-interpreted, re-mixed, and re-worked. What makes you return to certain songs? Nowadays it’s a little bit taboo to say, “Oh, we cover songs.” People joke and say, like, “Oh, are you a cover band?” But a lot of the most timeless music ever was people interpreting other songs. I listened to a lot of Roberta Flack before this week. I was going to sleep while finding YouTube videos of Robert Flack, who is best known for “Killing Me Softly,” which she didn’t write. But does anybody know who wrote it? You’d have to do a deep dive and listen to this one podcast and really research who wrote it. But it’s a Roberta Flack song, like Santana’s biggest hit, “Oye Como Va.” I mean, if you, you know, some, most people at this point have heard that it was a Tito Puente song, but it’s, it’s the Santana song. I’m just a big fan of interpretation. With all the boleros, very few of those people wrote those songs. And it’s about what you bring to it and what you do to it and what kind of feeling and emotion you put into it.

What makes you return to a song?

It’s a number of things because sometimes, like I said, I’m not a singer or a songwriter like that. So a lot of times I’m attracted to the production and the sound and the instruments and the performances. But then if a vocalist or a singer is emoting something in a certain way, I don’t really know what I’m attracted to. I think the first thing I listen to mostly is the music, to be totally honest. But I love when people kind of breathe new life into a song and put their own spin on it.

Do you find boleros to be a musical lingua franca of sorts for Spanish speakers?

Yeah, absolutely. It’s definitely another one of those genres, and I would say even more universal than [a genre like] cumbia in terms of the fact that most Spanish-speaking countries can do their own version of boleros and baladas and things like that. And you might not be able to spot where it’s from. You know, I think the perfect example is Los Angeles Negros, most people thought were from Mexico, but they’re actually from Chile. And they, you know, obviously they lived in Mexico for a while, but like you couldn’t, I think it’s easier in a cumbia to sort of listen and say, like that probably came from Columbia or that came from Mexico or Northern Mexico or that come from the way that they play things. But I do think that there is a universal language to boleros and baladas like that, where it’s probably a little harder to distinguish. It does become this thing that. That can unite a lot of cultures and parts of the world.