Author and historian Dennis McNally has written extensively on the Grateful Dead, including the 2002 authorized biography “A Long Strange Trip.” In his new book, “The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties,” McNally (who also served as the Dead’s publicist in the 1980s and 1990s) looks at the larger cultural moment that the band was part of. This excerpt looks at the story of the first Be-In, which featured a performance by the Dead for an audience full of counterculture luminaries.

At 1 p.m. on Jan. 14, 1967, Gary Snyder blew into a conch shell to begin the Gathering of the Tribes, the Great Human Be-In, fulfilling what Kenneth Rexroth and Robert Duncan had begun 25 years before. It was a moment — in all senses — of high optimism and joy, an essentially spiritual event to celebrate life and community, not at all Western in its purposelessness.

It was also the beginning of the end of the Haight as a functional neighborhood. At least 30,000 people sat in front of Snyder on the Polo Field in Golden Gate Park, and what had been only modestly noticed to that point would now pass into legend via an astonishing media scrum.

Although Michael Bowen was perhaps the first to talk it up, the notion of a large celebration was a complete natural for a neighborhood that was itself an ongoing celebration. The phrase “Be-In” came from the USCO artist Steve Durkee (or, one authority wrote, Gerd Stern), who passed it to Richard Alpert, who shared it with Bowen. To choose the day, someone approached one of the Haight’s resident astrologers, Gavin Arthur, who’d been a socialist and New Ager since the 1930s, a friend of Robinson Jeffers and also of Edward Carpenter, thus linking him to Walt Whitman and revealing a deep connection to American bohemianism. Roots. He chose wonderfully well; mid-January days in San Francisco are often miserably wet and raw, but this one was glorious.

Jay Thelin, whose appearance was relatively conventional — a low bar in his circle — went to the city’s Recreation and Parks Department to get a permit and found a brand-new person in charge, assistant supervisor of recreation Peter Ashe, a bearded Haight Street sympathizer. The hippies got their papers.

On Jan. 6, the Barb headlined the beginnings of the human be-in… a gathering of the tribes. It would serve as a love feast that included both Berkeley and the Haight in a “new and strong harmony.” Naturally, the Oracle went all out. The cover was literally purple: an Indian sadhu with three eyes designed by Bowen from a photo by Casey Sonnabend, a painter and sometime drummer for Ann Halprin, with decorations by Stanley “Mouse” Miller.

Allen Cohen agreed with the Barb: “We emphasized the unity of political and transcendental ideals, and we had a preference for non-violence.” The roots, Cohen said — “Beats, LSD, anti-materialist, idealistic, anarchistic, surreal, Dionysian and transcendental” — were held in common. One of the most perceptive of the Berkeley radicals, Michael Rossman, felt that “the Movement had expanded beyond all political bounds and recognition, and was on some verge — perhaps premature, but real enough — of carrying us through deep transformation into a new human culture.”

On Jan. 12, Snyder, Bowen, Jerry Rubin of Berkeley’s Vietnam Day Committee, Cohen, and Jay Thelin held a press conference at the Print Mint poster shop on Haight Street to spread the word. “The days of fear and separation are over.…All segments of the youthful revolutionary community will participate.”

The night before the Be-In, the poets met at Michael McClure’s home on Downey Street in the Upper Haight to plan the program. The main point of contention seemed to be identifying Timothy Leary as a poet (seven minutes) or a prophet (half an hour). It concluded when Allen Ginsberg quipped, “If he starts to preach, Lenore can always belly-dance.” The bulk of the day would be musical, but the recognition of the Haight’s roots in Beat poetry was essential. Coupled with psychedelics and rock and roll, the day would also stand for the shamanic and environmental vision represented by both McClure’s biologically based mysticism and Snyder’s profound connections to Indigenous culture and Buddhism.

Rumors of a Satanic curse on the event skittered around the Haight, so early on the morning of the 14th, Ginsberg, Snyder, and Alan Watts conducted a pradakshina, a Buddhist purification rite. The poets — Lawrence Ferlinghetti, McClure, Lenore Kandel, Ginsberg, Snyder — kicked off the day with readings, Kandel realizing that the day was about genuine community, about trust, because she was surrounded with people “that belonged to me and I belonged to them.” Rubin raged against the war. Leary burbled his advertising slogan. The Diggers passed out thousands of hits of Owsley Stanley’s finest and served turkey sandwiches, which Stanley had also contributed.

Strangely, the SFPD had apparently chosen to ignore the Chronicle, their entire presence that day consisting of two mounted policemen observing from a nearby hill. When a lady looking for a missing child approached them, they suggested she go to the stage and call for assistance: “We can’t go down there, lady, they’re smoking pot.”

Ralph Gleason estimated the crowd at 20,000; other guesses ranged quite a bit higher. Every tribe that felt connected to the Haight had shown up, from Big Sur and Carmel in the south, to the gold country east of San Francisco, to Sonoma and much farther north. Persuaded by his students, the abbot of San Francisco Zen Center, Suzuki Roshi, attended and sat by the stage smiling and holding a flower. Dizzy Gillespie was there. Two unknown actors named Gerome Ragni and James Rado would channel the day into writing a play called Hair. The queen of groupies, a visiting Pamela Des Barres, was disturbed by the split ends of hair she saw around her but was able to see the obvious: “Everyone was smiling and glad to be alive on the planet… knowing the world could be saved if we loved one another.”

There was trouble with the power source at some point, and the Hells Angels guarded the line and felt useful. Quicksilver Messenger Service played, and “Girl” Freiberg felt the same as Des Barres: “This is just like a really big family.” The Grateful Dead kicked off their set, which would also include Charles Lloyd on flute, with “Dancing in the Streets,” and Dizzy Gillespie pronounced them “swinging.”

A parachutist landed on the field. Sprawled out on blankets, people blew bubbles, shared oranges, lit incense, and gave one another small presents of bells and mirrors. They looked around astonished at the sheer number of people who were part of the gathered tribes. Ginsberg, who had whispered to Ferlinghetti when sitting on the stage, “What if we’re all wrong?” ended the day by urging everyone to practice kitchen yoga and clean up — and they did so, leaving the field immaculate.

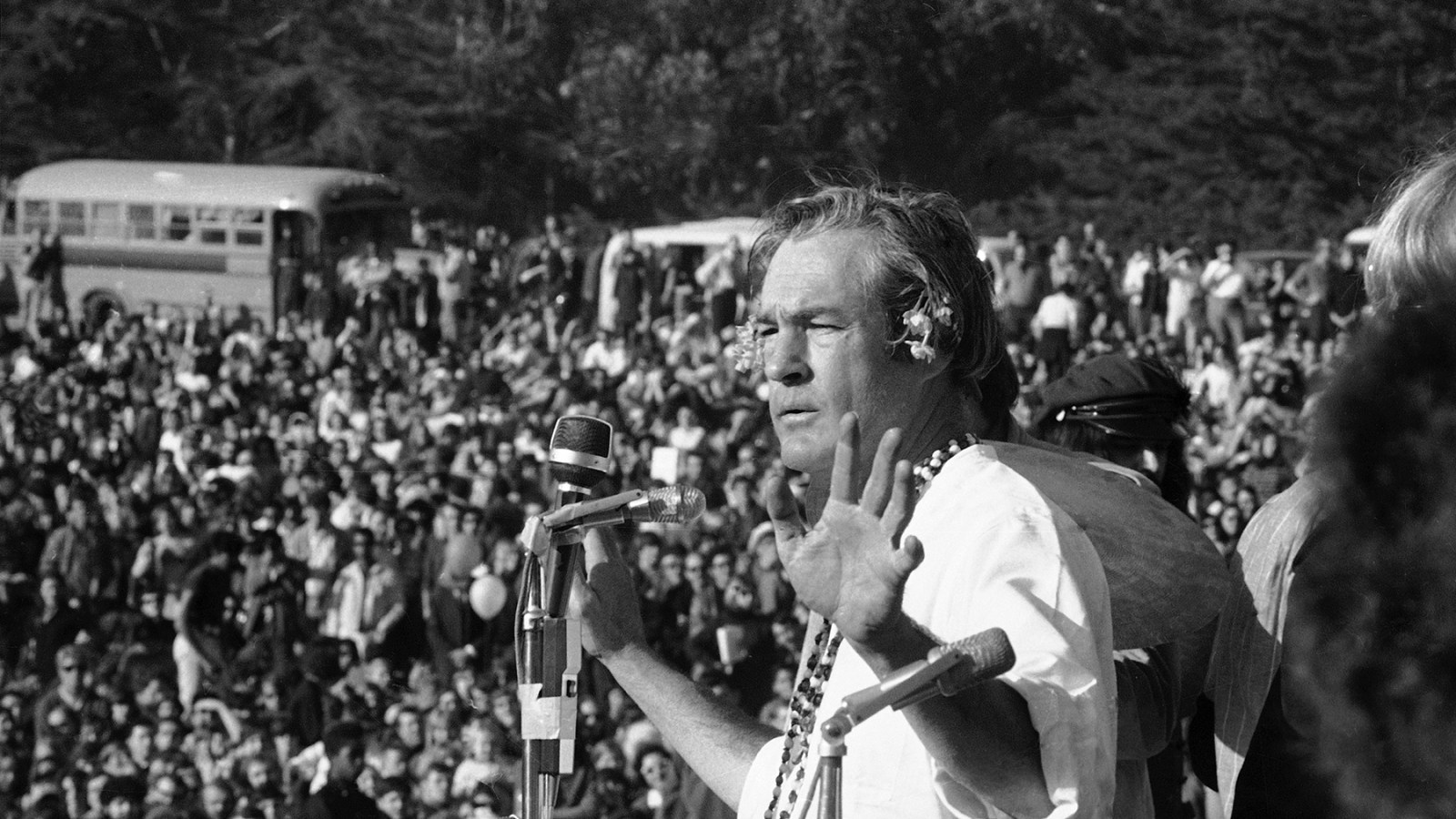

Allen Ginsberg (center) with Timothy Leary (with back to camera) at the Great Human Be-In.

Bob Klein/AP

“No fights. No drunks. No troubles,” reported Gleason. “An affirmation, not a protest. A statement of life, not of death, and a promise of good, not evil.”

“My day was full,” said the Dead’s co-manager Danny Rifkin, smiling.

Though the police had essentially ignored the gathering, they managed to make up for their kindliness by gratuitously arresting around 100 youth on Haight Street for “blocking traffic” as they drifted home. The hip response would be HALO, the Haight-Ashbury Legal Organization formed by Brian Rohan and Michael Stepanian, young members of Vincent Hallinan’s law firm, who would get all charges dropped.

McClure would declare that “the Be-in was a blossom. It was a flower. It was out in the weather. It didn’t have all of its petals. There were worms in the rose. It was perfect in its imperfections. It was what it was — and there had never been anything like it before.”

Even a black-belt cynic like the writer Hunter Thompson responded to the day. “There was a…sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting — on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum. We were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave.” At least one Berkeley politico, ED Denson, would write that “nothing happened at the Be-In, and the opportunity to gather all of those people was wasted.” Few attendees would have agreed.

By now, Allen Cohen noted, the Oracle was not a newspaper but a “journal of arts and letters for the expanded consciousness — a tribal messenger from the inner to the outer world.” Most importantly, the Oracle had switched to a new printer, which allowed them, said Cohen, to “use the presses like a paint brush” by splitting “the ink fountain of a web into three compartments with metal dividers and wooden blocks,” with a different color ink in each compartment. Now Cohen really had his rainbows.

In something approaching formal journalism, the Oracle in February gathered Timothy Leary, Gary Snyder, Alan Watts, and Allen Ginsberg at Watts’s home on the Sausalito waterfront, the SS Vallejo, for what was intended as a serious conversation about where the burgeoning alternative society might go. On the whole, the conversation came down to a sane, sober, and practical Snyder challenging Leary’s airy platitudes, which began and effectively ended with “turn on, tune in, drop out.”

A few years later, Snyder would offer the following quote to a speaker’s bureau representing him: “As poet I hold the most archaic values on earth. They go back to the late Paleolithic: the fertility of the soil, the magic of animals, the power-vision in solitude, the terrifying initiation and rebirth, the love and ecstasy of the dance, the common work of the tribe. I try to hold history and wilderness in mind, that my poems may approach the true measure of things and stand against the unbalance and ignorance of our times.”

Later still, in Earth House Hold, he summed up his stance as a faith in “the ancient shamanistic-yogic-gnostic-socioeconomic view, that mankind’s other is Nature and Nature should be tenderly respected; that man’s life and destiny is growth and enlightenment in self-disciplined freedom; that the divine has been made flesh and that flesh is divine; that we not only should but do love one another.” Such views, suppressed by church and state, now seem “almost biologically essential to the survival of humanity.”

Peering through a roseate fog, Leary predicted that, through LSD, groups of youth would “open one of those doors” and see “the garden of Eden, which is this planet,” thus changing their consciousness. Snyder replied, “But that garden of Eden is full of old rubber tires and tin cans right now, you know?” What was important, he argued, was that “people learn the techniques which have been forgotten; that they learn new structures and new techniques. Like, you just can’t go out and grow vegetables, man. You’ve got to learn how to do it.”

If our culture was to change its relationship to the natural world, it had, he offered, a superb example at hand in Native American culture. Since the central problem of the exploitive modern capitalist society was consumption, Snyder also suggested group marriage as a way to lessen demand. His life had been an ongoing example of “cutting down on your desires and cutting down on your needs to an absolute minimum, and it also meant don’t be a bit fussy about how you work or what you do for a living.”

Leary suggested that we “dig a hole in the asphalt and plant a seed…do it on the highway so they then fix it and when they do we’re getting to them. There’ll be pictures in the paper” — publicity apparently being the solution to everything. He concluded, “All right. We’ll change the slogan. I’m competing with Marshall McLuhan. Everything I say is just a probe.”

A flyer for the first Be-In.

Blank Archives/Archive Photos/Getty Images

About the same time as the conversation, Snyder and Ginsberg created and carried out a ritual that they offered as a way of both showing gratitude to the planet and clarifying one’s own mind — namely, a circumambulation of Mount Tamalpais, the guardian mountain that looks down on the San Francisco Bay Area. The legend of Tamalpais had been romanticized and appropriated by Anglos as “the sleeping Indian maiden,” most notably in a 1921 Mountain Play (there is an amphitheater near the summit that hosts an annual play) called Tamalpa.

The Beat response reclaimed the mountain as sacred. In 1965, Snyder and his friend Philip Whalen had designed a hike in the Japanese mountain monk (yamabushi) tradition that followed a route with stations where the pilgrims stopped to chant from various Zen and Tibetan Buddhist traditions, something not only Buddhist but shamanic. In the wake of the Be-In, they led their first public circumambulation on Feb. 10, 1967.

Snyder’s poem, “The Circumambulation of Mt. Tamalpais,” would become the centerpiece of his late-life masterwork, the fruit of 40 years of writing, Mountains and Rivers Without End. After taking tea with the artist Saburo Hasegawa at the American Academy of Asian Studies on April 8, 1956, he vowed to write a long and serious poem, and he completed it four decades later. It is a meditation on a classic Chinese landscape painting, something meant to be an invitation to mindfulness in Zen much as a thangka is in Tibetan Buddhism. The poem is a spiritual autobiography, a depiction of ecosystems, and a series of snapshots, all of which reflect one another.

It might well be one of the most important artistic consequences of the Be-In and the Haight-Ashbury scene.

Excerpted from the book “The Last Great Dream” by Dennis McNally. Copyright © 2025 by Dennis McNally. Reprinted with Permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.