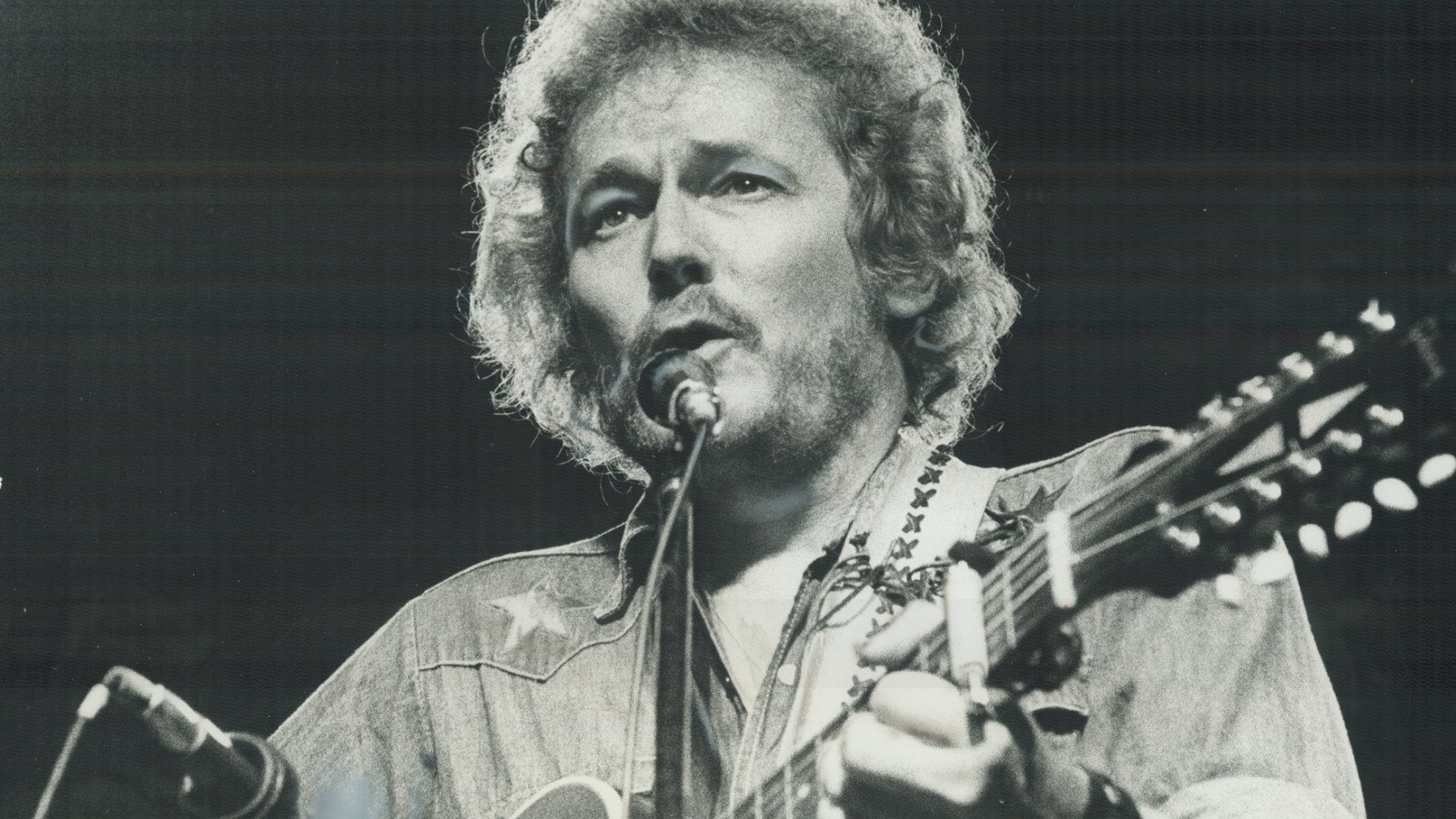

On the night of Nov. 10, 1975, was perched in the attic of his Toronto home, working on a song. By then, the 36-year-old was already one of the most successful figures of the singer-songwriter era, having penned coffeehouse standards like “If You Could Read My Mind” and “Early Morning Rain,” and he earned the admiration of Bob Dylan (who once said, “I can’t think of any Gordon Lightfoot song I don’t like.”) His 1974 album, the folk-country opus Sundown, had recently hit Number One on the Billboard 200, spawning hits with both the title song and “Carefree Highway.” But it wasn’t all chart success and good vibes; in the Seventies a bout of Bell’s palsy would partially paralyze Lightfoot’s face, and later in the decade he developed a severe drinking problem. The songs weren’t so mellow, either — the easy-grooving “Sundown,” for example, was about infidelity, the chorus a warning to another man pursuing his girlfriend.

On that November evening, Lightfoot was playing around with a melody from an old Irish dirge he’d heard as a kid; he had the tune, but no lyrics — not yet. Around 10 p.m., Lightfoot took a break and headed down to his kitchen for a cup of coffee. Lightfoot, a recreational sailor, took note of the rough weather. “The wind was howling even in Toronto,” he said, “and I went back up to the attic thinking, ‘I wonder what it’s like up on Lake Superior.’ It must’ve been awful.”

It was: That same night, the Edmund Fitzgerald, a mighty Great Lakes freighter, would sink, taking the lives of its 29 crew members with it. The tragedy would soon reverberate around the country — and give Lightfoot the inspiration for his next song.

“The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” is a remarkable pop artifact — a wordy six-minute ballad with no chorus and a deep devotion to the facts of what really happened on Nov. 10, 1975. Despite — or, more likely, because of — these qualities, the song reached Number Two on the Hot 100 in 1976 and became one of Lightfoot’s best-known songs.

In his new book, The Gales of November: The Untold Story of the Edmund Fitzgerald, bestselling author John U. Bacon tells the story of the Fitzgerald in compelling detail, in the process delivering a rich history of Great Lakes shipping. (The oceans tend to get the glory, but the seasoned sailors say the Great Lakes are at least as fearsome, and Great Lakes shipping, in so many ways, made America’s auto industry possible.)

Late in The Gales of November, Bacon — who’s written books on leadership and college football, among other topics — devotes two chapters to Lightfoot’s epic ballad. So much of the unlikely story is about Lightfoot’s obsessive attention to detail and commitment to getting the story right, which resulted in a classic ballad that has helped keep the ship’s memory alive.

“Anyone writing a book about the Edmund Fitzgerald has to be humble enough to acknowledge that without the song, there is no book,” Bacon says. “How can I be so sure? Between 1875 and 1975 the Great Lakes claimed a staggering 6,000 shipwrecks — that’s an average of one per week, for a century — yet most people can only name one. Clocking in at over six minutes, with no chorus or hook, Gordon Lightfoot’s song never should have become a hit. But it did, and I think it’s because of the bone-deep sincerity he brought to the task. He meant every word, and listeners can tell — including the victims’ families.”

Read an excerpt from The Gales of November on the making of “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” below.

Courtesy of W • W • NORTON & COMPANY

The Ballad

After the Edmund Fitzgerald sank on Monday, November 10, 1975, Gordon Lightfoot read Harry Atkins’s Associated Press story in the Los Angeles Times, then Jim Gaines’s piece in Newsweek two weeks after the wreck.

Lightfoot biographer Nicholas Jennings tells us Lightfoot read the opening line of the Newsweek story “and was instantly captivated.” “When the Edmund Fitzgerald went down I imagined what that wave might have been like,” Lightfoot said. He added that the Newsweek piece “really moved” him, but it struck him that the twenty-nine men deserved more than a half page in a national news magazine.

Lightfoot felt that he was getting close on his sea shanty melody, which seemed to fit his subject’s somber and mysterious mood, so he started working on the words.

“It was quite an undertaking to do that,” he said. “I went and bought all of the old newspapers, got everything in chronological order.”

With the AP, Newsweek, and other stories laid out in front of him, Lightfoot began by writing about “the big lake they call Gitche Gumee,” the “load of iron ore” that weighed twenty-six thousand tons, “the gales of November,” and “the maritime sailors’ cathedral,” where “the church bell chimed ’til it rang twenty-nine times/For each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald.”

The troubadour had done his homework.

The song’s 478 words, just 56 shy of the Newsweek article itself, told the story with both economy and feeling, two masters that are hard to please in one song.

Still, Lightfoot remained deeply unsure of this piece, particularly his lyrics, due to the sensitivity of the subject. He feared being inaccurate, corny, or worse, appearing to exploit a tragedy for profit. But more than that, as a fellow sailor and a child of the Great Lakes, and as a musician whose first song he ever recalled was now playing in his head, decades later, this song — whatever it was — was deeply personal. It was something he felt.

Lightfoot couldn’t put the song out of his mind, tinkering with it for months — but always keeping it to himself.

BY DECEMBER OF 1975, Lightfoot felt he had enough songs ready for his next album, Summertime Dream. It was time to gather his longtime bassist Rick Haynes, guitarists Terry Clements and Pee Wee Charles, and a new drummer, Barry Keane, to rehearse the tunes in the solarium of Lightfoot’s home.

Lightfoot took a working man’s approach to his music, and he expected his band to do so, too. After practicing long hours Monday through Friday, Keane recalls, they had about a dozen songs “in pretty good shape. But at the end of each rehearsal Gord started strumming this new song, in six-eight time, which you don’t hear very often. Terry and Pee Wee would work out parts of it. Rick might have played a note or two, that’s all, and I never played a single beat on it.

“But before they ever got going on it Gord would always stop and say, ‘No no. It’s not ready yet. Don’t worry about it. Look, this is a song about a shipwreck — a real one.’ ”

Then Lightfoot would drop the subject, every time.

In the spring of 1976 Lightfoot summoned his band to Eastern Sound Studios on Yorkville Avenue in Toronto for a five-day session, noon to six each day, to put Summertime Dream on vinyl. In the meantime Lightfoot had figured out how the guitar parts for his new sea shanty would go, but he still wouldn’t dare sing the lyrics to anyone, nor did he plan on recording the song for this album, if ever.

But the pattern held. On Monday, after getting a handful of songs polished enough to put “in the can,” Lightfoot started fiddling with the sea shanty again, but shortly after the others joined him he abruptly stopped.

“No, no, we’re not doing it.”

The same thing happened Tuesday, and again Wednesday: After getting a few more songs on tape, he’d start playing the new song, and then shut it down.

“It isn’t ready,” he insisted. “And it’s not going to be on the album.” The band still hadn’t heard the whole song, just some chords and bars, and no lyrics.

By 3 p.m. on Thursday they had finished recording ten songs for the new album, a full day and a half before their studio rental ran out.

“Gord said, ‘Okay, we’re done. Thank you guys.’ ” Keane says. “This was back in the Seventies, when no one finished early. But we were a tight group, and knew what we were doing.”

The bandmembers had already started packing up when studio engineer Kenny Friesen hit the talk-back button in the booth to speak to the band. “What about that shipwreck song?”

Lightfoot once again protested that it wasn’t ready.

Friesen countered, “Look, you’ve got the guys here and you’ve got the studio booked for five days. You’re paying for it either way. Might as well try it.”

“There was a long pause,” Keane recalls. “Then Gord said, ‘All right.’ ”

Lightfoot turned to his guitarists and said, “Terry and Pee Wee, do your thing.”

Keane, lost, had to speak up.

“When do you want me to come in?” Lightfoot’s drummer had never played a single note on the mystery song to that point, and had no idea what Lightfoot wanted.

“I’ll give you a nod,” Lightfoot said. Since Lightfoot would be sitting across from Keane, right outside the drum booth, that seemed simple enough.

Lightfoot asked Friesen to turn the lights down, which set the mood, then paused, closed his eyes, and started strumming the song’s first notes. When he was already ninety seconds in — approaching the entire length of most popular songs — he still hadn’t given Keane the nod to start, so Keane figured he had forgotten him, and the song was about to end.

“But no,” Keane says, “right before the third verse Gord gave me a nod, just like he said he would, and I jump in.”

At exactly 1:34, right after Lightfoot sang, “And later that night when the ship’s bell rang/could it be the north wind they’d been feelin’?”

He nodded to Keane, who came in with a strong tom fill, to mimic a storm crashing down. It was a bold move, especially for someone who hadn’t yet secured a full-time spot in Lightfoot’s band — and exactly the right one.

“None of us had heard the whole song,” Keane explains. “So we all just played what we felt.”

Right after Keane’s thunder, Lightfoot sang, “The wind in the wires made a tattle-tale sound/and a wave broke over the railing.”

Keane had provided the perfect transition to the storm itself. It’s impossible to imagine the song without it.

After twenty-eight two-line stanzas, lasting five minutes and fifty-eight seconds, they reached the end of the song, improvising the entire way — then looked at each other, pleasantly surprised.

What was that?

Whatever it was, Keane says, “it was actually pretty darn good. But Gord’s a perfectionist, so he says, ‘Well, we should try it again.’ So we tried it again. Then maybe a third time. Then Gord says, ‘We’ve got another day of studio time, so let’s try it for real tomorrow, and do this thing right.’ ”

On Friday they played it again three or four times, Keane says, “but we never got it as good. The first time we played it the day before, there was that creative tension. Gord was putting his heart and soul into it. You can hear it. The other guys felt the same tension, because we’d never heard the song, and nobody wanted to screw it up. And that tension led to some good stuff. We weren’t thinking. We all just played what we felt.

“You’re always trying to make it better — but each time you play it, it takes some of the soul out of it, because it becomes more clinical, more technical. You want to perfect it, but that song didn’t need to be perfected. It needed to be raw, organic.”

When they played back the various takes, they reached a surprising consensus: The first take on Thursday was their best. “That’s it,” they said. “That’s the one.”

But Lightfoot’s band was not a democracy. He had the only vote that mattered, yet to their surprise he agreed with them: The first take was their best. The version people have been hearing on the radio for decades is actually the first time the band ever played the song.

“Look, if you’re not in the music business, you probably don’t know that first takes get on albums sometimes,” Keane explains. “But the first time you ever played the song? Never. Never, never, never. That never happens. And it almost didn’t happen that time. It was that close. The album was done!”

When they left the studio, they all felt that they had created something special.

“But did I know it was going to be a hit?” Keane asks. “Not a chance in hell. It was long. Six minutes. It didn’t have a chorus. It didn’t have a hook, no ‘Yummy yummy yummy, I got love in my tummy.’ It didn’t check any of the boxes you need for a hit. I didn’t think it had a chance to be a hit — and I was in the record business.

“No. No chance.”

The Edmund Fitzgerald in 1972

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

An Unexpected Hit

SHORTLY AFTER THE album came out the band appeared on The Midnight Special, a popular show featuring live music, to promote Lightfoot’s new album, Summertime Dream. The album had eleven songs, and they played six that night — but not “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” which they felt was too long, with little commercial appeal.

A few months later Lightfoot and his band traveled to Los Angeles for a series of shows at the Universal Amphitheatre. While in town Warner Bros. asked Lightfoot to meet with Mo Ostin, their president, to discuss which song to push as a single from the Summertime Dream album. Lightfoot asked Keane to come along.

“We sit down,” Keane says, “and Mo says, ‘You know what, Gordon, we’re getting some reaction to the shipwreck song on FM.’ ”

When Ostin asked Lightfoot what he thought of turning it into a single, Lightfoot and Keane looked at each other “in complete disbelief,” Keane says. “We know Mo’s a smart man, but really? We couldn’t believe what we were hearing.”

Almost everyone personally attached to the Fitzgerald remembers the first time they heard, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.”

John Hayes was working on the ST Crapo. He and Helen planned to get married on August 21, 1976, though the death of his best man, Fitzgerald oiler Tom Bentsen, naturally hung over them.

“It was a windy, nasty night on Lake Michigan,” Hayes says. “I’d just helped load the coal for the boilers with a flashlight. When we finished, I hopped on my bunk with my AM radio and I just happened to hear Lightfoot’s song that night. First time.

“It was eerie. Man, he got it right.

“The biggest thing for me is the opening guitar riff. Everyone knows that now. No matter what I’m doing when the song starts, I hear that, and I stop. Gets to me. Every time.”

The unlikely single topped the Canadian chart, the U.S. country chart, and finished 1976 on the Billboard 100 chart second only to Rod Stewart’s “Tonight’s the Night,” a song that checked all the usual boxes for a hit: short — at three minutes and thirty-four seconds, almost three minutes shorter than “The Wreck” — peppy, with a memorable chorus and hook, plus the bonus of Stewart’s girlfriend, Britt Ekland, cooing in the background, the “Me Generation” personified. It embodied everything “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” did not.

“I just listened to ‘The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald’ for the first time in a while,” Rolling Stone editor Christian Hoard says, “and I have to say it’s remarkable that it was such a big pop hit: no chorus, no bridge, no hook, just the same melody repeated over seven eight-line stanzas for nearly seven minutes. I mean, ‘Hotel California,’ another dark and lengthy story song from the same era, still had a chorus and an amazing guitar coda.

“I’d venture ‘Wreck’ is one of the wordiest top five hits until rap came along. Compelling melody for sure, but I have to assume that what people loved so much was hearing the story in such detail. That’s some old-school troubadour stuff, a ballad in the classic sense.”

Perhaps Hoard’s insights explain why Lightfoot was so reluctant to share it in its embryonic stage. Lightfoot’s song broke all the rules, and he knew it. But Hoard is right: The story was too compelling to ignore. Like Lightfoot’s sources, the AP’s Harry Atkins and Newsweek’s Jim Gaines, Lightfoot cared about the Edmund Fitzgerald more than he had to, and people could feel it.

A few months after the meeting with Warner Bros.’ president in Los Angeles Lightfoot’s band played a tour stop at Kalamazoo, Michigan’s K-Wings Stadium. It holds about five thousand people, but packed six thousand that night. “I can still see their faces pressed up against wire screens around the stage,” Keane says. “It was like that for the whole concert — but you can imagine how it got amped up when we played ‘The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.’ ”

In addition to the song’s unusual structure and forbidding length, the tune was limited by Lightfoot himself, who refused to market the piece in the usual manner.

“Gord wasn’t big on playing hits,” Keane says with a chuckle. “He would always say, ‘To thine own self be true.’ At our concerts he liked to play his favorites. We’d say, ‘Hey Gord, why don’t we play “Carefree Highway”? Big hit, everyone likes it.’ And he’d say, ‘Ah they all know that one.’ Right! Isn’t that the point?

“He drove Warner Bros. absolutely nuts! We’d produce a new album, and not tour, because Gord was afraid people would think we’re just trying to sell records. Well, wasn’t that the idea? A very Canadian response. A very Lightfoot response.”

And yet, Lightfoot’s stubborn purity is surely why listeners recognize his sincerity in memorializing such a tragic event. The next year he accepted an invitation from the Reverend Ingalls, the pastor who rang the bell twenty-nine times, to play at the Mariners’ Church in Detroit. Lightfoot brought only Terry Clements and Rick Haynes, a barebones band.

“Just us, and a small amplifier playing at the front,” Haynes says. “As simple and pure as it gets.”

After they finished the song Reverend Ingalls approached Lightfoot, appreciatively and respectfully, to point out that Mariners’ wasn’t a “musty old hall,” as Lightfoot’s lyrics said, but clean and bright.

Lightfoot agreed. Whenever they played the song after that, he changed the lyric from “musty old hall” to “rustic old hall.”

One of the theories investigators had posited to explain the Fitzgerald’s sinking was improperly clamped hatches, which prompted Lightfoot to write one of his most famous stanzas:

When suppertime came, the old cook came on deck

sayin’, “Fellas, it’s too rough to feed ya.”

At seven p.m., a main hatchway caved in

he said “Fellas, it’s been good to know ya”

After investigators were able to send a submarine to examine the ship 530 feet below the surface, they discovered that Fitzgerald deckhands Mark Thomas, Paul Riippa, and muscle car aficionado Bruce Hudson had, in fact, done their jobs correctly, to the great relief of Hudson’s mother, Ruth. Lightfoot changed that lyric, too: “At seven p.m., it grew dark, it was then he said ‘Fellas, it’s been good to know ya’”

“That’s how much Gord really cared about ‘the wives and the sons and the daughters,’ ” Keane says.

Bassist Rick Haynes agrees. “Gord wanted the families to have peace.”

Lightfoot even double-checked lines in the song that were verifiably accurate.

“One time Gord and I had a heated argument,” Haynes says. “He said, ‘It can’t be twenty-six thousand tons. That’s impossible! It has to be twenty-six hundred tons!’

“Gord, you got it right the first time,” Haynes said. “That’s what those ships carry!”

Lightfoot and his bandmates have been careful about how and where they play it, too. When Jimmy Fallon wanted to do a comedy bit based on the song, Lightfoot rejected the idea out of hand, before it could go anywhere.

The fear Lightfoot had of being perceived as an opportunist, especially by the families, was dispelled.

“I had quit following the Fitzgerald story,” former Fitzgerald deckhand Patrick Devine says. “I just couldn’t deal with it emotionally. But when the song first came out the next year, I was furious! I felt like a lot of people were taking advantage of other people’s suffering. I was really irritated.

“But the following year I was at one of the memorials when Helen Bindon, widow of Eddie Bindon, who had been so good to me, came up to me and said, ‘Have you heard that new song?’ She appreciated it — even if I didn’t. It stunned me. Well, she lost her husband, and she loves the song, so what’s my problem?”

Like Devine, when Marilynn Church Peterson, one of the five children of Fitzgerald porter Nolan Church, heard the song for the first time, “I hated it. My first thought was he just wants to make money off it.”

Marilynn’s view changed twenty-six years later, on May 5, 2002, when she and five family members went to see Lightfoot and his band play in Duluth. After a moving concert, Lightfoot invited them all backstage.

“When I heard him play it live I knew he really cared about the song,” Marilynn says. “And backstage he asked what I thought of it. I assured him it was a great tribute. He truly cared about all the families involved — and I felt that he truly cared about my feelings.”

Like many of the survivors, since the sinking Marilynn Church Peterson has never gone back out on Lake Superior, the lake she grew up on. As a rule, the younger the survivor, the more likely they were to succumb to self-medication through drinking and drugs. Most ultimately came out of it, but not all.

“It was very hard on Mike,” Bonnie Church Kellerman says, referring to their youngest sibling, who was just seventeen when their father died. “He had a really hard life after that, and chose the wrong direction,”

Marilynn says. “At that age, I don’t think he ever got over it.”

The families have little choice but to savor the silver linings, including the song itself.

“Our dad has so many grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and now even great-great-grandchildren,” Marilynn says. “They never got to meet him, but they love the song, and at family functions we always play it.”

Cindy Reynolds, Bruce Hudson’s girlfriend, remembers the immediate effect the song had on her and Ruth Hudson.

“We listened to it and listened to it,” Reynolds says. “And Ruth thought it was unbelievable that he could put together those words that fast. She wondered how he could know how it felt, because it felt like he did.

“Even now, when I hear the song, it gets me reminiscing about Bruce. And sometimes I have to pull over, and listen in peace.”

That might be Lightfoot’s best review.

Lightfoot, after the unexpected success of “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” pulled out of his tailspin, got clean and sober, and embarked on thousands of concerts over the next four decades.

If Lightfoot was initially uncertain about his new song, by 2002 he knew exactly where it stood in his body of work. He told Roger LeLievre, then at The Ann Arbor News, that “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” “is my greatest achievement. It’s a song you can’t turn your back on. You can’t walk away from the people either. The song has a sound and total feel all its own. We’ve sung it at every show since the day we wrote it. It’s a true song and a great song. It’s stood the test of time.”

Former Great Lakes Maritime Academy superintendent John Tanner met Lightfoot a few times backstage with the GLMA scholarship recipients. “If I had to pick one word to describe him and his music,” Tanner says, “it’s ‘pure.’ Gordon Lightfoot is pure.”

That explains why fans, from overseas to the Fitzgerald families themselves, are so attracted to “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”: It’s a true song.

For the fortieth anniversary of the sinking in 2015, bassist Rick Haynes and Lightfoot flew from a concert in Utica, New York, on their only day off from their tour, to the Upper Peninsula, then drove to Whitefish Point for an event — and not to play, just to be there with the families.

“I remember walking out to the water off Whitefish Point,” Haynes says, “and sitting in the sand, and just looking out there. This is a song that I’ve sung thousands of times, and the men we sing about are just fifteen miles out there.

“So close to safety. It gets you.”