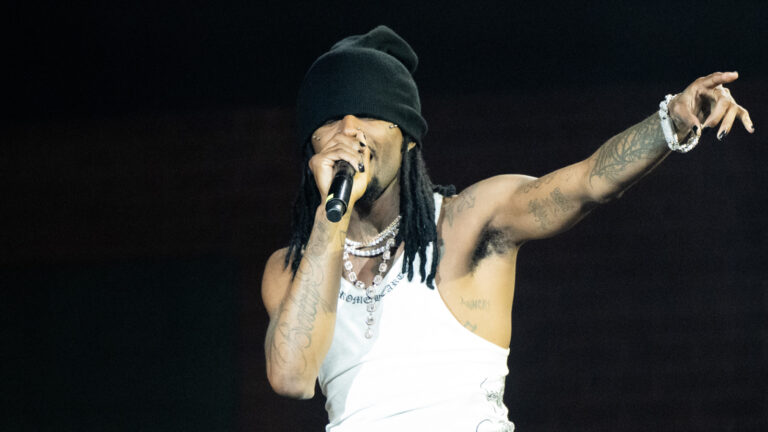

On a picturesque morning in late July, the rapper Aminé is perched at a cobalt blue dining table in his airy Hollywood home. As he and three close collaborators fine-tune the artist’s upcoming setlists, one of his most important musical inspirations gazes out at them from a wall flanked by floor-to-ceiling windows: In a house brimming with playful primary colors, the most commanding sight is a grayscale portrait of Aminé’s mother.

The simple image is all the more striking because its source material was hardly hi-res: Aminé recalls seeing his mother’s small passport photo for the first time while visiting his grandparents’ house in Ethiopia several years ago; the poster-sized print now framed on his wall is an enlarged rendering of a picture he snapped with his iPhone before leaving the faded original in its place. Its provenance happens to mirror some of the themes animating Aminé’s most recent album, which draws heavily on the musician’s East African heritage. With evocative art direction, wistful songwriting, and spirited production, 13 Months of Sunshine reflects the distinct complexities of the Portland native’s upbringing as a child of Ethiopian and Eritrean immigrants.

13 Months of Sunshine enters the world during a notably fraught time for the region where Aminé and I have shared roots: Six years after Ethiopia’s prime minister was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for thawing relations with neighboring Eritrea, the two nations are on the brink of another war. Meanwhile, amid ongoing political violence on either side of the historically contentious border, a rise in unfettered hate speech on social media has further fractured the countries’ diasporas. The heightened ethnic tensions back home and the ripple effect among Ethiopian and Eritreans around the world weighed on Aminé as he worked on the album. “I was like, Is this the right time to do this?” the rapper says. “It felt so divided for the past, like, five years.”

For Aminé, the salience of recent conflict has opened up a new window into understanding his parents, who moved to the States in the early 1990s and raised their children in a multi-ethnic household. Hearing the pain that the violence causes them “made me realize, Oh, this is why my dad didn’t teach me to [only] be prideful of me being Amhara or prideful of me being Oromo,” he says. The new record is almost defiantly curious, searching rather than authoritative. And as Aminé gears up for the start of a stacked fall tour, the artist seems as invested in learning more about all the places that shaped his family as he is in seeing a laundry list of major cities around the world. He’s lucky, he notes, to be reminded of home anywhere he goes: “Because what I do for a living as an artist, all the Eritreans, all the Ethiopians, they all be at my shows and it’s all love at all times,” he says. “In my eyes, I’m doing it for all of them.”

Nine years after the infectious summer hit “Caroline” introduced a baby-faced 22-year-old named Adam Daniel to the world by his middle name, 13 Months showcases the eclectic sensibilities of a 30-something who’s matured as both an artist and a son. While his father’s influence is obvious through the interludes he voices on the new album, including on an opening track named for Ethiopia’s capital, Aminé’s mother has had a more subtle impact on her son’s music—one that comes through more clearly in the new record than on any of his previous releases. The rapper credits his mom with expanding his musical horizons when he was young, partly by playing her own wide-ranging selections around the house: Along with expected names such as Michael Jackson and the famed Ethiopian singer-songwriter Aster Aweke were the likes of Keith Urban, John Mayer, and Rascal Flatts. She also curated personalized selections just for him: When Aminé requested CDs for Christmas, “I wouldn’t even specifically ask for certain artists,” he says. “My mother would just go and buy [albums] based on the things I’ve bought in the past.”

With a laugh, the artist confesses that he became way more open to his mom’s non-hip-hop offerings after a middle school crush introduced him to one of the songs he’d eventually interpolate on 13 Months—hellogoodbye’s 2006 synth-pop banger, “Here (In Your Arms).” The resulting song, “Cool About It,” is at once energetic and vulnerable. It’s the kind of charmingly melodic anthem that begs to be belted alongside friends mid-way through a great party, in part thanks to giddy, layered production from Lido, Buddy Ross, Jim-E Stack, and Pasqué. “Cool About It” is one of the more pop-inflected 13 Months tracks, while others, like the deviously catchy singles “Arc de Triomphe” and “Vacay” come out swinging with hi-octane allusions to U.K. garage and house grooves.

Aminé’s first project steeped in the propulsive percussion of dance music, 13 Months still sounds like the summer, but it also signals a refreshing artistic confidence—and a willingness to reject the constraints that he’s sometimes felt boxed into as a rapper. “I knew I had so many ill rap songs that I didn’t put on this album,” he says. “In all the years of me making albums now, I feel like the one thing I’ve learned is to just commit to whatever you’re going for—no matter if it’s rock and roll or whatever the fuck, just commit.”

13 Months is clearly a product of that ethos. Though some fans attribute the new sound primarily to the artist’s recent collaboration with Kaytranada, Aminé notes that 13 Months has been in the works since well before the world met Kaytraminé (and even before he and the Haitian-Canadian producer connected over Soundcloud back in the early 2010s). In fact, some of Aminé’s most formative musical memories took hold on Sunday mornings back when he was nowhere near old enough to step into a nightclub on a Saturday night: “The Habesha music I would hear at church had the tempo of dance music where it is not your average one, two step,” Aminé explains, using a colloquial descriptor for Ethiopians and Eritreans.

In the Orthodox Christian churches attended by many Ethiopians and Eritreans, the kebero, a conical, double-headed drum is a centerpiece of liturgical music. In some ways, the instrument’s stuttering beats echo the “swing” that Kaytranada tends to nudge him toward in the studio, too—an intentional move away from the tidy confines of an anticipated beat: The kebero reverberates forcefully at polyrhythmic intervals when clergy members play it with their bare hands during worship—and elicits frenetic applause, a kind of call-and-response, from the congregation. “I was raised on that kind of rhythm,” Aminé notes, adding later that “every time they hit the kebero, that rhythm and that sound was so influential to me.”

There are no liturgical chants sampled on 13 Months of Sunshine; for all his occasional raunch, Aminé says he wasn’t inclined to commit outright blasphemy. But the varied syncopation and intense emotional registers of Orthodox worship music informed his approach to an album that balances weighty introspection with buoyant production and evocative imagery. Aminé says he knew early on that he wanted the album’s creative direction to highlight the decor he was surrounded by growing up, and its cover art features visual hallmarks of many Ethiopian Americans’ living rooms: There is, of course, the framed meskel, or cross, just to the left of his head and the medosha, or horsehair fly swatter, to the right. The other two items on the wall hold more poetic significance: The poster on the far left bears the old Ethiopian Tourism Commission slogan from which the album borrows its name, a reference to the country’s calendar—and, in particular, to the final month.

Each year, after 12 months of 30 days, comes 5 or 6 days of Pagume, which is often considered a time for forgiveness and blessing. “When I saw the meaning of that month, it’s supposed to be a rebirth and a time for growth, that’s what I felt like this album’s contents were for me,” Aminé says. Working through some heavy decisions as he stepped into a new chapter of adulthood has been a taxing endeavor, he notes, so “I was like, Oh, this embodies what I need, basically. I wish I had 13 instead of 12 in this moment.” The clock behind him signals that wish on a smaller scale; it has one extra hour marker, with the 13th one most prominent.

13 Months is Aminé’s most lyrically mature offering to date, a departure from the lighter fare that some fans have come to expect. Midway through the Leon Thomas-assisted opener, “New Flower!” we hear a recording of Aminé’s father relaying some of his own childhood memories to his American-born son. (The song’s title is the English translation of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital city, where Aminé’s maternal grandparents still live.) Speaking about the Eritrean grandfather for whom Aminé is named, his father says: “I used to do gardening / With Grandpa Aminé / He force you to plant / And keep it maintenance and everything / So after you come from school / Then he go to the garden / And maintaining it, uh, giving it water, stuff like that / This is how I grew up.”

It’s a tender recollection, one clearly meant to impress upon his only son the importance of hard work and nurturing the things he loves most—no matter how far he might be from the countries where his family has deeper roots. Part of what makes “New Flower!” so compelling is that the fruits of both older men’s labor become clear almost immediately after the story. In the next verse, Aminé raps candidly about the pressures of making it in the industry: “I am depressed / If people don’t like me, then I don’t get a check / Which means both my parents are stayin’ in debt / and I prefer to be the only one that carries the stress.” It’s an understandable sentiment, certainly for many children of immigrants who’ve seen their parents struggle in a country that seems to grow more hostile by the day. And at the start of “Doing The Best I Can,” another message from Aminé’s father nods to that very idea: “I have to do something for this / family I created, you know? / I try my best, I tried my best possible effort.”

The resplendent title track underscores that theme, too: Right after the deliciously frothy “Raspberry Kisses,” “13MOS” kicks off with a disarmingly cheery chorus. Aminé sings the album name between melodic stylizations of East African ululation, then glides into two light-hearted, dexterous verses riffing on Ethiopian names and cultural staples in a way that feels like a more grown-up version of “Baba,” a single from way back in 2017: In the second verse alone, he crowns himself a “skinny leg legend,” laments that Portland makes it “hard to meet a Feven,” points out our collective affinity for Hondas and Toyotas, then caps it off with a little nod to eskista. When Aminé cedes the mic to his father, who opines on the difficulty of adapting to “the language barrier, the culture barrier,” the entire tenor of the song shifts. In the second half of “13MOS,” Aminé’s raps take on a contemplative tone as he reckons with what he’s inherited—including the weight of his name. But 13 Months, which ends with a haunting Aster Aweke sample, doesn’t slip into the cliché of treating the artist’s father more like an idea than a person.

That’s partly because the rapper didn’t originally intend for his recordings to end up on the album. They’d come from a series of conversations on a father-son trip to the Oregon coast in January, when his father started sharing some life lessons as the two walked along on the beach with their dogs. “I just, like, record my grandparents or my parents now that they’re older. I know these are the kinds of voice notes I want to hear when I get older as well,” Aminé says. It wasn’t until he played it for his friend and tour DJ, MadisonLST, that the parallels with his own lyrics became clear. Taken together, the messages lend 13 Months of Sunshine’s vocals an intimacy that delivers on the invitation of its cover (especially the delightfully rebellious one at the end of “Vacay,” one of the album’s best tracks).

That same feeling is palpable throughout the 13 Months visuals, some of which took Aminé back to Ethiopia this spring for the fourth time in his life. If the album interludes convey wisdom from Aminé’s dad and late grandfather to the 31-year-old, then the artist’s performance in an Addis Ababa skate park captures the effervescence of an even younger generation. Meanwhile, a roadtrip visualizer filmed all around the city made me so nostalgic I nearly impulse-bought a plane ticket the first time I saw it. Aminé’s version of Addis Ababa has always been oriented around his family, especially his grandparents. “As soon as my career took off and I could afford a ticket, I went back. And then I went back again,” he says, citing the prohibitively expensive airfare to Africa as he describes the gaps between his first visit as a teen and subsequent trips. “Every time I’m there, we’re not talking about me. We’re talking about the drama within the neighborhood, their lives, and catching up with them,” he adds later. “I’m trying to soak up so much of their stories and their lives.”

When I met up with Aminé in Los Angeles earlier this summer, he, Madison, Lido, and Paqué were preparing for the second edition of The Best Day Ever Festival, which the rapper started last year in Portland. But a few short months after his trip to Addis Ababa, the city was still top of mind, especially as he chuckled at feedback from fans who’d guessed that he would release an album packed with samples of Ethio-jazzclassics. Making time for his grandparents had still been a core element of his latest visit to Ethiopia, but he experienced the country differently this time—both as an artist and as a diaspora kid who daydreams about spending longer stretches immersed in Addis Ababa’s youth culture. “That trip completely changed my ideology of Addis as a city, of being just a place where I went to go see family,” Aminé says. He credits a lot of his newfound comfort to the people who readily welcomed him into the city’s dynamic creative scene (and gave him a glimpse into its nightlife, too). Whether shooting in the skate park, location-scouting in Mercato, or navigating tech issues with less-than-ideal WiFi setups, the rapper “felt like I was just in my neighborhood growing up,” he says. “It felt like I was really home this trip.”