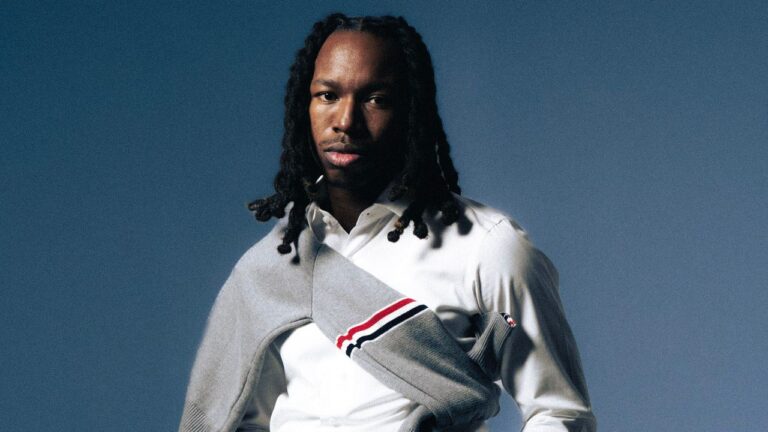

Sam Canty knows the power of a Treaty Oak Revival concert, but he long ago stopped trying to make any sense of it. “I can’t believe I’m making somebody feel like this or act like this,” says the band’s frontman of the crowd-surfing and beer-hurling that seems to follow the five-piece on the road.

After a two-year run in which the group went from clubs to theaters to arenas, buoyed by a string of platinum and gold singles and one of the most exciting live experiences in all of music, Treaty Oak Revival are on the brink of bona fide superstardom. The independent outfit’s third studio album, the 14-track West Texas Degenerate that dropped on Friday, is poised to remove that “brink” caveat for good.

It’s also an album that finds a band who rocketed to fame in Texas with songs about prostitutes (“Fishnets”) and whiskey (“Ode to Bourbon”), growing up.

“The point of this record was to show growth and what that means,” Canty tells Rolling Stone. “Overcoming addiction, finding love, just stuff we haven’t really talked about in our songs. We come from a small town where, when you were young it was drinking and partying and having a good time, and not really caring about the world or having any responsibility. Eventually, you get thrown into the real world and you realize that the real world doesn’t care about your plans. You’re going to assimilate whether you want to or not.”

What that real world even is for Treaty Oak seems to change by the hour.

The band consists of Canty on lead vocals and Jeremiah Vanley on lead guitar, along with Vanley’s nephew, Lance Vanley, on rhythm guitar. Cody Holloway plays drums and Dakota Hernandez stepped in on bass this summer after founding bassist Andrew Carey left the band in June. They came together in Odessa, Texas, in late 2018, playing music as a hobby. They’ll close out 2025 with back-to-back headlining gigs at Oklahoma City’s Paycom Center and Dickie’s Arena in Fort Worth, along with a New Year’s Eve show at the Toyota Center in Houston. They’re managed by the same management team — Bob Doyle & Associates, the only managers Garth Brooks has ever had — that oversaw Zach Top’s rise to stardom. Four years ago, Treaty Oak were a local bar band in Odessa, so you’d have to forgive the group for not yet fully grasping what it means to play to thousands, or on occasion, tens of thousands of fans every night.

“At the beginning of this year, our stage manager yelled at me for the first three shows because I kept wrapping up cables to put up in the box,” Lance Vanley says. “He would go, ‘Stop touching stuff! That’s why you hired me!’”

Before Treaty Oak played the first show of a three-night stand at the 5,600-capacity Whitewater Amphitheater in New Braunfels, Texas, in August, the members gathered in the green room to reflect on their breakthrough moment and look ahead to West Texas Degenerate. By then, Treaty Oak had already released a pair of songs, “Happy Face” and “Bad State of Mind,” that also made the cut for the new record. Both songs cracked the top 30 on Billboard’s country chart, and “Happy Face” has been certified gold.

“We chose those two because it’s kind of both sides,” Canty says. “I feel like there’s two sides to this record — there’s a really heavy, dark side, and there’s a lighter, upside of the record. ‘Happy Face’ was a good representation of the light side and ‘Bad State’ was a good representation of the heavier stuff.”

Canty grew up the son of a journalist and with a grandmother who was an author, but music was the only writing that made sense to him. Sure, he was heavily influenced by the Texas and Red Dirt scene that dominated his region. He cites Randy Rogers, the Turnpike Troubadours, Reckless Kelly, and Ryan Bingham as influences. But he was also fascinated by old-school hip-hop, particularly freestyle. He also knew he wanted to play for a living. “I’d always wanted a band, I just didn’t know where to look,” he says. “I didn’t know there was one 15 minutes from my house playing in the back of a shop.”

Jeremiah Vanley had been in a cover band in Odessa, but the lead singer lost interest. In late 2018, he’d been playing for fun with Holloway and Carey in the back of a vacuum repair shop, when the owner suggested he invite Canty to jam. His gravelly, metallic vocals brought the cover songs to life. By 2019, Lance Vanley had joined. They named themselves after the Treaty Oak in Austin, a sacred meeting place for the Comanche and Tonkawa natives. Soon after, they realized Canty couldn’t just sing. He could write too.

“When I joined, I wasn’t even aware if we were going to be a band or if we were just hanging out for that one night a week,” Lance Vanley says. “Another month or two into it, learning more cover songs, we started talking: Do we want to maybe be a cover band, or start to play at bars? Then Sam said, ‘I write songs.’ I hadn’t heard his originals, and I said, ‘Let’s hear ’em.’ Turns out, they weren’t half bad.”

The band recorded its first album, No Vacancy, in 2021, not intending for it to be released beyond the group’s merchandise tables. Canty says he got tired of being asked at shows if the band had music on streaming services, so they decided to record a record to shut up the fans clamoring for Treaty Oak music. No Vacancy has since gone platinum, as have two of its singles, “Ode to Bourbon” and “Missed Call.”

“We found a guy in Odessa in like this home studio and recorded it,” Jeremiah Vanley says.

“He actually came over the other day, because I told him I had some stuff for him. I gave him three gold records. He’s like, ‘What is this?’ We kind of feel the same way.”

They followed that with 2023’s Have a Nice Day. It debuted in the Billboard 200, and suddenly Treaty Oak became much more than a bar band. They began climbing festival bills and opening for the likes of Koe Wetzel. They caught the attention of Pat Fielder, a senior buyer for Mammoth Live, an independent promotion company heavily focused on the Midwest that had a history of booking Texas acts in places like Kansas City and Des Moines. In 2024, Fielder experienced Treaty Oak’s growth firsthand. He’d book the band for a certain-size venue and then find they had outgrown it exponentially by the time the concert happened.

“Treaty started out doing what most bands do as they head north on I-35,” Fielder recalls. “Play the clubs and sell them out. Play the theaters and then sell them out. They did that quickly. We did some shows with them where they supported acts like Koe Wetzel, Ian Munsick, and Whiskey Myers throughout the year. As each one played out, you could see more and more fans there specifically to see Treaty Oak.”

Fielder recalls a sold-out show in Des Moines as a high-water mark. “The band broke just about every record you could break in the room that night, and they did it with a punk rock work ethic, which I think really contributes to their success,” he says. “These guys are as much a punk rock band as they are a country band.”

When it came time to record West Texas Degenerate, Treaty Oak Revival collectively realized they were here for the long haul. But they also had families and children, and Canty swore off alcohol in late 2023.

By the time Have a Nice Day was released, Canty had already moved on to what eventually became West Texas Degenerate. In a bout of homesickness, he scribbled down lines like “Okay, I fucking love and you know sometimes I miss you too,” which became “Happy Face.”

“I wrote that the day we uploaded Have a Nice Day,” Canty says. “We were in Gulf Shores, and I had called my wife. We had been on the road for a long time through the Southeast and I hadn’t seen her in a while. I hung up the phone, and the guys were all in a restaurant. I remember thinking, ‘It’s crazy that here I am having the time of my life with my friends, but I am wishing I was with my wife, wishing my family was here.”

Canty wrote all 14 songs on West Texas Degenerate, with three co-writes. William Clark Green helped Canty write the title track when the two men holed up one afternoon in the green room at Billy Bob’s Texas. Gannon Fremin, whose group, Gannon Fremin & CCREV will open Treaty Oak’s Oklahoma City and Houston shows, co-wrote “Withdrawals.” Gary Stanton of Muscadine Bloodline co-wrote “Misery” along with “Arsonist,” which made the cut on Muscadine’s Longleaf Lo-Fi record released earlier in November. All three co-writers also sing with Treaty Oak on this record.

“We just wanted to make some cool music with our cool friends and put it out for the world to hear,” Canty says.

One of those friends is Austin Meade, another Texas country-rock hybrid who opened the first Whitewater Show for Treaty Oak in August. Meade and Canty have been friends for nearly a decade, and they host a series of holiday shows every year they have termed the “Meade-E-Oak’r Christmas Vacation Tour.” This year, they’ll play those shows in Ardmore, Oklahoma, and Lubbock, Texas, the weekend before Treaty Oak’s Oklahoma City concert.

Along with the friendship, Meade sees a model in Treaty Oak Revival for his own career.

“I get a lot of hope for what we’re doing when I see so many people in the world grasping on to what they’re doing,” Meade says. “Those people are looking for something real. That can be said about many genres, but what these guys are doing and what Koe’s doing — it’s just real shit. They’re super nice folks, but they still got that dog in them. Like, don’t get on their wrong side.”

Until this year, Treaty Oak barely had a reason to have a wrong side at all. But with success has come criticism — mostly of the band’s beer-throwing live shows. The group isn’t girded for a fight the way Gavin Adcock seems to be on the same topic, but they are aware they’ve put some people off as they’ve grown. The members have largely avoided confrontation, but that’s because their day-to-day manager, Eli Kidd, watches over them, particularly on social media. Canty calls Kidd the Gavin Adcock of Treaty Oak for his habit.

“If I see false information, I will talk shit,” Kidd says. “I don’t care if you talk some shit, but make sure that your information is accurate.”

Canty says bogging down in negative comments online would take away the sheer joy of the ride that Treaty Oak have been on.

“Now we’re getting haters — quite a bit of haters, actually,” he says. “I don’t mind it, man, but I feel it adds fuel to the fire, gives you something to work towards. You just take it with a grain of salt. Most of the time, a few people say it’s shit, but millions of people say it’s badass. Who cares? It’s your music. If people like it, cool. If not, there’s a bajillion other artists you could go listen to.”

Regardless of how people feel about beer throwing, a Treaty Oak Revial show is one of the most high-energy concerts around at the moment. Fans show up to sing along, crowd surf, and drink to the backdrop of a dizzying light show. During the group’s recent headlining set at the Red Bull Jukebox concert in Nashville, the crowd went wild for their signature, “Boomtown,” and a cover of Blink-182’s “All the Small Things.”

The band can sense a crowd’s energy even before the show starts. And they feed off it. Before they took the stage at another Nashville show in 2024, at the sold-out Brooklyn Bowl, band members worked themselves into a frenzy just out of the crowd’s view, crushing beers and yelling, “Fuck shit up!’ to each other before walking on.

“We all lean in every night,” Hernandez says, “but there are some nights that you can tell, there’s something in the air. You’ll hear that guy in the background go ‘Awoooooo!’ and you’re like, ‘They’re ready!’”

For Treaty Oak to have reached this point in five years’ time serves as much as a reality check as it does a measure of success. The sheer joy the band gets from playing to whichever sold-out crowd it happens upon is always going to be juxtaposed against the fact Treaty Oak Revival almost happened by accident. The band is only around at all because a group of friends in Odessa wanted to jam once a week. That they somehow parlayed it into a way of life is not lost on the group. It’s why they promise to keep playing songs as long as Canty keeps writing them.

“I’ll take it to my grave as long as it’s helping people,” Holloway says. “If it’s still out there and it’s helping somebody, getting somebody through the day, I’ll keep playing ‘til the day I die.”

Josh Crutchmer is a journalist and author whose book (Almost) Almost Famous will be released April 1 via Back Lounge Publishing.