A

T HIS REGULAR SPOT — the stool with “BG” on the back, way at one end of the bar — the owner of Buddy Guy’s Legends scans the hundreds of people packing his club. Tugging off the pandemic-era mask he still wears during public gatherings, he leans forward and looks toward the stage a few hundred feet away. “In an hour,” he says, “I might have a drink and go up there.”

On some level, this midsummer evening is just another night at the Chicago blues club and restaurant Buddy Guy opened more than 35 years ago. The tables atop the yellow-and-blue checkerboard floor are once more filling up with tourists, tattooed dudes, youngish couples, and blues fans of all stripes. The walls remain lined with photos of Guy onstage and offstage with his disciples (Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan) and his heroes (B.B. King, Muddy Waters). The employees at the merch counter near the entrance are prepping to sell T-shirts, baseball caps, and other souvenirs sporting Guy’s likeness or the club’s logo.

When he’s not on the road, Guy stops into his club regularly, partly to keep an eye on operations, but also to goose the business, since customers sometimes show up hoping he’ll take the stage whether he’s on the bill or not. But tonight isn’t just another booking; as a banner over the bar proclaims, it’s his birthday, his 89th at that. Looking at Guy, you’d barely know it: His complexion is smooth, and he appears trim and wiry in his polka-dot jacket over a white T-shirt, topped by one of his trademark white caps. Fans approach to wish him happy birthday and give him a casual fist bump. Guy acknowledges each quickly, then signals to a bartender, who brings over a bottle of his favorite cognac.

Some of tonight’s crowd have likely been fans of Guy’s for decades; others might know him as the older incarnation of Sammie Moore in the closing scenes of Sinners, director Ryan Coogler’s acclaimed and top-grossing blues-and-vampires hit. “It seems like every time I go to the grocery store, I hear, ‘That looks like that guy in Sinners,’” Guy says with a smile. Easing his way off his stool, Guy makes his way to the merch area to begin signing copies of his just-released album, Ain’t Done With the Blues, and pose for selfies with the Guyheads lined up out the door.

But after an hour, his work for the night has just begun. Called over to the stage, he accepts a birthday cake with candles from some of the eight adult children and several grandchildren gathered around him. As the house band slips into a bluesy vamp, the family members leave the stage, but Guy remains, and the reserved, elderly gentleman at the bar transforms into the wily, suggestive Buddy Guy of legend. “If you don’t love me, maybe your sister will!” he growls, to laughter and cheers. After a half hour, he heads back to the merch stand and resumes the autographing and selfies, but the crowd wants more music. When a microphone is passed to his side of the club, Guy picks up where he left off onstage, wandering into the crowd this time, and exhorting more blues. He won’t leave until 2 a.m.

The sight of Guy summoning up the energy of someone decades younger is startling, even to his family. “We’re always like, ‘Oh, my God — he’s old and is going to fall,’” says his daughter Shawnna Guy, a hip-hop artist since the Nineties. “You look at him onstage, and he’s just bopping back and forth and hitting the strings with a face towel, then putting the guitar behind his head and playing it with a drumstick. And you’re like, ‘What the hell am I worried about?’ I can’t even do that!”

Guy’s ongoing livelihood — Ain’t Done With the Blues is his 20th studio album, and he’s leaving for a string of West Coast shows a few weeks after we meet — is not necessarily the outcome he or anyone saw for himself. For the first few decades of his career, he was often overlooked and undervalued by the music business. But now, the blues pioneers who inspired him — King, Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Guitar Slim, and so many more — are long gone, as are many who learned from him, from Jeff Beck to Vaughan. Guy, the blues stalwart who couldn’t catch a break for a long time, has outlasted them all.

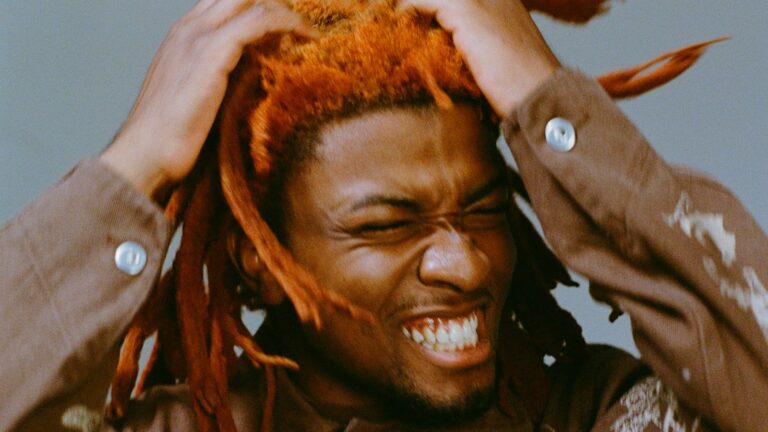

“I’m the last old man still walking and playing the blues,” he says. “That’s what we talked about with Muddy [Waters] and Howlin’ Wolf before they died. They said, ‘Buddy, please keep the blues alive.’ And I’m tryin’.” As youngblood blues guitarist Christone “Kingfish” Ingram puts it, “As far as mainstream blues, he’s the last OG.”

Guy in the 1960s

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

One key to Guy’s survival is that he was never a blues purist. Dating back to his earliest 45s and his first album, 1967’s Left My Blues in San Francisco, he blended soul, rock power chords, and high-stepping R&B into blues, along with an unrestrained style of guitar playing and vocal blues wail that always threatened to go off the rails but never did. His recent string of albums are packed with cameos from across the musical spectrum (Mick Jagger, Keith Urban, and Kid Rock, among many) and sport a loud, crackling, radio-friendly sound; Ain’t Done With the Blues, which was just nominated for a Best Traditional Blues Album Grammy, pairs him with Ingram, Joe Walsh, and Peter Frampton. As Bruce Iglauer of the blues label Alligator says, “Buddy effectively rocked out the blues, while keeping the soul of the blues in the music. I don’t know that anybody else has done that. Maybe he feels like he’s the last knight in armor, and that part of his job is not repeating the tradition, but bringing the tradition into a more modern context.”

Thanks partly to Sinners and musicians like Ingram, the blues appear to be in healthier shape than in a while; Ingram has started an independent label to foster new talent in the field. “I’ve seen a lot of young artists of color coming out and playing this music, or music based on this genre,” he says. “People are craving more music that’s authentic.”

But once we lose Guy, we won’t just see the passing of a musician who took blues guitar to new, crazily inventive heights, influenced everyone from the Rolling Stones and Clapton to Vaughan and Ingram, and managed to have a rare second act in the music world. We’ll also be losing a vital link to the music’s roots and the cultural backdrop from which the blues emerged. Simply put, we will never see the likes of Guy again. “We have to accept that these younger artists didn’t grow up as sharecroppers, didn’t grow up in the Civil Rights Movement,” says Shawnna. “So their stories are not going to be similar.”

No one knows all that better than Guy. He has played for or met three presidents, though not the current occupant of the White House, whom he views skeptically. (“The man is a rich man, a rich person, and he got golf clubs here and there and all that stuff,” Guy says. “He ain’t with no poor man,” adding sarcastically, “And he’s thinking about me and you.”) Guy remembers the night in 2012 when he was in the White House, part of a salute to the blues during President Obama’s first term. “You know, I made a joke out of it,” Guy says with a grin. “I said I was picking cotton on the farm with an outhouse, all the way to the White House. Some people laughed at that, but it’s true, man. I tell people, ‘Not a lot of you know what an outhouse is.’”

Long Road to Success

For at least the past three decades, the blues have been good to Buddy Guy, evidence of which is amply on display at his compound in Orland Park, just outside of Chicago. Tucked away in a thicket of trees on five acres, the estate includes a house with five bedrooms, an indoor pool, and a private residence for his groundskeeper. In his kitchen, complete with shelves lined with his favorite spices for cooking, a stash of white birthday roses has arrived from Carlos Santana, along with a card from Coogler and his wife, Zinzi. “Like you see,” Guy says, seated at his skylight-drenched dining room table the morning after his birthday bash at Legends, “I got a pool table out down there. I grew up on the farm. There’s no such thing as a pool table on the farm, man. You had a hole where you chopped cotton. That’s the only stick I had.”

As usual, Guy has been up early, since about five in the morning, meaning he’s only had three hours of sleep. That schedule is another reminder of the life he had, nearly a century ago, growing up in a cabin on a plantation with no running water and wooden (not glass) windows. Born George Guy in Lettsworth, Louisiana, in 1936, Guy came of age in a sharecropping family that would give half of its proceeds to the landowners, spending his days picking cotton in brutal heat. “It got to 112 every day in June, July, and August, and all we had was a big fucking straw hat,” he says, sporting another white cap and a plaid jacket this time. “When day break, you get your ass out there and come home and get in the tub and be ready to do it again tomorrow.”

At first, the Guy house had no electricity, meaning no radio nor record player. But Buddy’s life began to change when the 13-year-old heard a fieldhand bang out John Lee Hooker’s “Boogie Chillen” on a guitar, then taught young Buddy how to play it himself. Soon after, Guy was further drawn into the music after seeing Lightnin’ Slim play in a juke joint. Buddy’s first guitar, which his father bought for him, had only two strings.

Lawrence Agyei for Rolling Stone

Moving to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1951, Guy worked on a factory conveyor belt and then as a maintenance man at Louisiana State University while he began playing gigs in roadhouses; another early hero, Guitar Slim, inspired him to pull wrenching notes out of his guitar. Moving to Chicago on Sept. 25, 1957 — a date he remembers so well that he’ll repeat it several times over two days of conversation — he found work in clubs and recorded for a local blues label, Cobra. One fateful day, he brought a tape of songs he’d cut at a Louisiana radio station to Chess Records, Chicago’s leading blues label.

Guy began logging time as a session guitarist, capable of backing up anyone from Waters to Koko Taylor (check out his contributions on her “Wang Dang Doodle”) and Howlin’ Wolf (same with “Killing Floor”). “They would call my house because they couldn’t get this guitar player down to play the rhythm they wanted,” he says. “They say, ‘If y’all want it done right, call Buddy Guy.’” But he also began busting out his own moves. Taking a break during a club set one night, he put his guitar down and forgot to turn it off; a customer walking by accidentally brushed her dress against the instrument, making for a joyful noise and leading Guy to experiment with distortion and reverb. His showmanship began ramping up, too. From the stage, he’d often venture out not just into the audience, but also sometimes outside the club and into bathrooms, still playing, his guitar cord trailing behind him. “When everything was so traditional, he came with a different sound, being wild and crazy,” says Ingram. “I like to credit him as being like the forefather of this bluesy, rock-y sound; Jimi [Hendrix] saw that and took it to a whole other level.”

Chess began releasing Guy singles, like 1960’s smoldering “First Time I Met the Blues,” but Guy’s tenure with the label proved to be one of several missed opportunities in his career. Leonard and Phil Chess, who ran the company, didn’t quite know what to do with the twentysomething Guy. “The dominant sound of blues guitar at the time was the more controlled sound of B.B. King or Albert King, rather than being rocked out,” says Iglauer, who would later release one of Guy’s finest and wildest albums, Stone Crazy. “At the time, Buddy was trying to get a little crazier than Chess would let him.”

Chess pushed Guy to make jazz or novelty records (like “Gully Hully,” which was something like Chicago surf music), but none took, and Guy has said that Leonard Chess thought his guitar sounded like “noise.” Guy also has contended that the Chess brothers wanted to change his last name to “King” to make it sound as if he were related to B.B. or Albert. Marshall Chess, Leonard’s son and a veteran music-industry executive himself, admits that the Chess brothers didn’t appreciate Guy’s approach to guitar and preferred to keep him in the background. “There’s a rumor that my dad didn’t like Buddy’s playing,” he says. “That’s not true. My dad was highly superstitious about the backup bands, and he didn’t like adding new things when he had hits with the one before. I never knew how brilliant Buddy was. I don’t think anyone at Chess did.” Guy was slighted elsewhere, too, like the time he appeared on British television and was introduced as Chuck Berry. He took a job at a tow-truck company to pay the bills.

Blues royalty: John Lee Hooker, B.B. King, and Buddy Guy

Ebet Roberts/Redferns/Getty Images

Those days were trying in other ways for Guy. Tom Hambridge, the drummer and producer who would guide Guy’s later albums, once visited Guy in a dressing room and watched as Guy returned an expensive bottle of Rémy Martin XO cognac that was waiting, open, for him there. After he saw Guy do the same thing on other occasions, Hambridge finally asked him what that was all about. In a reminder of the racism that could dog blues artists, Guy told him that a broken seal on a bottle indicated potential danger. As Hambridge recalls, “He said, ‘Because I’ve been poisoned before. Back in the day, they spit in it or piss in it.’ He said he’s gotten sick before, so the bottle has to be sealed in the box.”

As would later happen with artists from Hendrix to Lana Del Rey, it would take another country to kick-start Guy’s career. Black radio stations in the States ignored him, but Guy became a hero for a crop of young, blues-loving British musicians, enraptured with his combination of thrash, distortion, and stage presence. Guy recalls once seeing “a white face” at one of his shows and assuming it was a cop; but, he says with a laugh, “it was Eric Clapton!” As Clapton would later write, “He created a huge, powerful sound, and it blew me away.… He was like a dancer with his guitar, playing with his feet, his tongue, and throwing it around the room.”

Jeff Beck, Keith Richards, Jagger, and more also worshipped at the altar of Buddy. (Many years later, Jimmy Page, another Guy disciple, told Guy’s son Greg that Buddy was “the guitar god.”) At first, Guy didn’t know what to make of the emerging counterculture that embraced him in the Sixties. “I saw the Stones coming with the high heels on, almost looked like a woman,” he recalls. “I’m saying, ‘What is this?’ I got to San Francisco, and I said, ‘Man, look at this.’ I didn’t know what a hippie was. I saw men with long hair. But they were going crazy [for my music], man: ‘What do you got in that amp?’”

But the bad breaks continued. As the Sixties drew to a close, Guy and his then-partner, harp player Junior Wells, became a must-see duo and were offered a chance to make an album produced by Clapton. But in the midst of his heroin addiction, Clapton bailed on the project, and the album sat in the vaults for two years before it tumbled out to an indifferent response. By the early Seventies, Guy no longer had a record deal and opted to open a club of his own, the Checkerboard Lounge, on Chicago’s South Side. “Without a record, it is getting hard to find places to stay,” he said at the time. He would often perform at the Checkerboard, but friends and customers, even family, were equally accustomed to seeing him sweeping up, doing inventory, or setting up for other artists’ shows.

Guy wasn’t averse to hard work, even in his own club. Here he is mopping the floor at the Checkerboard Lounge.

Marc PoKempner

Sometimes, even his kids didn’t quite know what their father did for a living, only that he would go on business trips and bring back enough money for piles of Christmas presents. Greg Guy’s classmates in high school would ask him if the “Buddy Guy” hanging out with the Stones — who hired him and Wells as an opening act on their 1970 European tour — was his father, and he wasn’t sure; to him, his dad was just George. At a block party in the Eighties, Greg remembers hearing loud music blasting out of a speaker and, without knowing what it was, decided to put an end to it. “I took the record off the turntable and threw it,” he says. “I didn’t want to hear it.” It turned out to be one of his father’s albums. Greg wanted to listen to Prince instead.

A Beautiful Second Act

In a rec room at Guy’s house, the mementos of his success are on display. Besides his many awards — including eight Grammys and a National Medal of Arts — there’s a sign proclaiming part of Highway 418 in Louisiana “Buddy Guy Way”; a thank-you letter Jagger wrote after Guy joined the Stones in New York in 2006 for the filming of the Shine a Light film (“It was so much fun & I can’t wait to see the film”); photos of Guy jamming onstage with Clapton, John Mayer, Susan Tedeschi, and others. A sculpture of a nude woman is mounted on the wall in a nearby bathroom.

A painting of Stevie Ray Vaughan takes up ample space on one wall. In August 1990, Guy, Vaughan, Clapton, and others jammed together at Alpine Valley in Wisconsin, then started to make their way out of the venue. Guy says he took a seat on a chopper meant for Vaughan, who would grab a later flight. “When my chopper come out,” Guy says, recalling the dense fog of the night, “I said, ‘Thank God we got out of there,’ because Stevie, Eric, and all of them wanted me to come cook for them the next day.” The following morning, Guy was heading out the door to buy gumbo ingredients when his wife told him there was a call from Vaughan’s people: The guitarist had been killed when his helicopter crashed into a ski slope. “Man, I couldn’t even …” Guy says, somberly. “I just sit back down. I couldn’t even move.”

Ironically, that period would also mark the beginning of Guy’s resurrection. With American roots music back in vogue in the late Eighties — thanks in part to Vaughan, as well as artists like Robert Cray and Los Lobos — Guy finally landed a major record deal, this time with the British label Silvertone. His first album for it, 1991’s Damn Right, I’ve Got the Blues, featuring cameos by Beck, Clapton, and Mark Knopfler, became the then-55-year-old’s belated breakthrough, selling half a million copies and garnering him his first Grammy (in the Contemporary Blues category). His daughter Shawnna, who didn’t realize her father was a “superhero” until she saw him in concert and watched the reactions to his manic stage act, noticed a change in status. “We moved from a one-car garage to a three-car garage that was the size of the house,” she recalls. “We used to have a Toyota and a van. Then in a flash, we had a Ferrari, a Rolls-Royce, and a Land Cruiser. I was just like, ‘Oh, my God, Daddy, you did it.’”

By then, another generation of blues players were discovering Guy — and his sly charms — for themselves. When she met Guy in the Nineties, Tedeschi was impressed with his musicianship: “His guitar tone was outrageous,” she says. “He could play anything. He was so wonderful to watch.” But she also encountered the seductive side of the tall, strapping musician with the head of curly hair. “He was real cute, and actually was real flirty with me one time,” she says. “Years later, he’s like, ‘I knew I should have asked you out.’ Then I was like, ‘Yeah, you should have, you would have had a chance back then!’” Guy’s reputation as a ladies’ man extended even further back: In the Sixties, Marshall Chess asked Guy for one of those mystical mojo concoctions that could supposedly attract women, and Chess recalls Guy giving him a “little pink cloth pouch, hand-stitched, stuffed with weird stuff like pig bristles.”

After the Checkerboard Lounge, Guy opened Buddy Guy’s Legends, which moved from its first location to its current one in 2010. Since January can be a slow month for business at his club, Guy began playing residencies at the beginning of every year. His newfound status was apparent in the fans tailgating outside the club — sometimes in subzero temperatures — to nab a seat to see their hero. The sidewalk outside Legends would be jammed with barbecue and fish cookouts. “There were two guys from Tennessee who were actual moonshiners and made 180-proof liquor,” recalls Mike Illingworth, the so-called Guy superfan and unofficial assistant. But the cold nights outside were, for Illingworth, tolerable. “There are lots of good players coming up, but not on the level of Muddy, Wolf, and Buddy,” he says. “Gary Clark Jr. is a great player, and there are four or five like that. But there’s a huge void after Buddy.”

Backstage with Stevie Ray Vaughan in New York, 1983

Redferns

Guy may not have been creatively or artistically satisfied during his years at Chess Records, but by the time he started receiving recognition, he had gleaned vital lessons from the experience, especially about the way blues musicians of the time were often ripped off or given raw deals. “I knew what was going on,” he says grimly. “I shut my mouth and watched them get fucked over, ’scuse my language.… I always hung around with men 20 or 30 years older than me, because I figured I could learn something from them. I couldn’t learn nothing from nobody my age because I knew what they knew.”

When Coogler was talking with Guy about casting him as the older version of Sammie in Sinners — a nod to an uncle of Coogler’s who is a big Guy fan — the director remembers Guy telling stories about visiting an older blues player, with eye-opening results. “He talked about going to one musician’s house who, in his eyes, was super successful, and sitting down on a couch, and his butt went through to the spring,” Coogler says. “He realized in that moment of pain the unfairness of it, because that musician was still living in poverty.” Guy has worked hard to avoid that fate. He owns his own music publishing, and in 2005 trademarked his own name.

Guy’s life experiences also infuse the records. In order to write songs for Guy, Hambridge would speak with him about his life. One of the results, “Show Me the Money,” from 2008’s Skin Deep, was rooted in Guy’s history of being exploited. “Buddy told me that back in the day, sometimes [club owners] wouldn’t pay,” says Hambridge, who recalls Guy telling him that he went onstage many nights thinking he should play so well that after the show, club owners would say to him, “I wasn’t going to pay, but damn it, here’s your money.”

Indeed, a conversation with Guy is a guided tour through blues history. A question about Willie Dixon, the bassist, songwriter, and producer who lorded over the Chicago scene, brings a frown. “Willie Dixon got credit for a lot of things he did not do, man,” he says. “Chess was taking from him, and he was taking from the musicians.”

But most of Guy’s stories are told with the rueful smile of a man who knows his days of being underappreciated and underpaid are behind him. He does an uncanny impersonation of Hooker, stutter included, and loves to recall the time Hooker got into a fight with, of all things, a little person over some women. Or the time Guy was recruited by the State Department to play concerts in East Africa, including one in Uganda under thuggish soon-to-be dictator Idi Amin. Guy says he wasn’t aware at the time of how murderous Amin could be. “I didn’t know he was cutting their fingers and sucking their blood,” Guy recalls with a laugh. “I [should have been] afraid I played the wrong note!”

Who does he miss the most? Guy pauses. “Well, I hate to pick one,” he says. “When I came to Chicago, B.B. King was hitting the strings on the gih-tar like nobody has ever done. But I can’t separate who I would say. Muddy, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, T-Bone Walker, Lightnin’ Hopkins. All them people like that. If I was to make a decision, I would say all of them.”

The End of the Road?

As the morning crawls along, Guy is stoned. Actually, he’s doing an imitation of getting high, recalling the days when he shared bills with the Grateful Dead and similar bands, along with the female fans who flocked to those acts’ shows. “Everybody was like this,” he says, closing his eyes and dropping his head back as if he were royally baked. “I’m looking at all these good-looking women. I said [to the musicians], ‘Man, is y’all having a good time? It’s a good time looking at that.’ I didn’t get ’em all. I didn’t want ’em all. But I said, ‘I’d love to be looking at this with a straight mind instead of getting high and got my eyes closed.’”

Guy’s survival can be attributed to his business savvy, but also to his lifestyle. He says he would turn to a “little whiskey” because he was shy and the alcohol helped calm his nerves before he’d go onstage. He still sips cognac from time to time, as he did at Legends. But he believes in moderation. Whether he’s in the studio or in other work situations, Guy often avoids food altogether. “My longevity is I don’t overdo nothin’,” he says. “I know how to quit eating when I’m full. If you eat too much, it’s going to do something to you. I was brought up like that: When you got enough, you got enough. Wait until tomorrow. You notice I took a couple of drinks last night. But I never been pulled over for drunk driving, and I never run over nobody, because I know when to stop.”

As Coogler saw for himself, Guy rarely stops. After a long day of production — and no meals — on the set of Sinners, it came time to film the live-performance footage seen at the movie’s end, with Guy ripping it up with Ingram and Hambridge. Despite the late hour, Guy seemed recharged. “By the time we wrapped, he just got warmed up,” Coogler says. “He didn’t want to stop performing.”

When Guy himself will quit the road remains a matter of debate. A supposed farewell tour in 2024 was extended into last year, and may continue into this year.

His family accepts the fact that he refuses to slow down. “We’re like, ‘Oh, Dad, don’t you want to sit down and enjoy the fruits of your labor?’” Shawnna says. “He says, ‘Is the bills gonna stop?’ We say, ‘OK, point taken.’ My dad is a country man. He comes from the South. He’s a hardworking man, and those core values are instilled in him so deeply. On top of that, when you get to that age, you got to keep moving. Once you stop moving, then everything shuts down on you, and we don’t want that to happen. We much rather see him up and smiling and laughing and loving what he’s doing.”

Still, Guy and his cohorts know his clock is ticking. “You better see him now,” says Illingworth, who has caught more than 1,000 Guy shows. “It’s like watching Pelé’s last game. It’s now or never.” As he demonstrated at Legends, Guy can get around on his own, slowly but determinedly.

But warning signs abound. Two years ago, he had to reschedule a string of shows for a medical condition, and at airports, his family has taken to making sure he can be transported around in a wheelchair. “He didn’t like it at first,” says Greg Guy, a blues guitarist in his own right. “He told me, ‘What are you trying to say? I’m old?’” Guy begrudgingly admits he has a few more aches and pains these days. “I’m sore today, put on some more [muscle-soreness] patches, and tomorrow it might go away,” he says at his home after the Legends night.

Then there’s the more urgent issue of who will keep the blues going after he’s out of the picture. Reflecting on the impact of Sinners, which is steeped in the Mississippi Delta blues of the Thirties, Guy says, “I feel it helps the blues a little bit, because there’s a lot of blues in there and [people have tended to] treat the blues like it’s a stepchild, especially if you’re Black. My grandkids know about it, but what about your grandkids? What worries me most, the young person don’t hear it anymore because they don’t play it no more.”

Ingram says he hasn’t had any direct talks with Guy like the ones Buddy had from his predecessors, but he knows Guy thinks of him among his successors. “He’s definitely mentioned me as one of the ones taking this genre on, and I’ve thanked him,” he says. Tedeschi says Guy has sat down with her and her husband, guitarist Derek Trucks, to talk about them keeping the music going after he’s gone. “It’s pretty heavy,” she says. “Those are very big shoes to fill.”

As the early afternoon approaches, Guy announces he’s going to retire — but in this case, just for his regular afternoon nap. His only concern is being awoken by robocalls and scam calls. Of the many hard-earned lessons he’s communicated to his kin, Guy is particularly proud to pass on another: about those scam phone solicitations and the way they prey on people for their money. “I told my son, ‘Would they be trying to get your charge-card number?’” he says. “I told him what to tell them: ‘You want my charge card? [It’s] F-U-C-K-Y-O-U.’” He laughs loudly and lustily. “When they call like that, they want something. Ain’t nobody gonna give you nothin’, man.”