I

n early 2017, Mike Smith, a suburban dad in his forties who owned a chain of urgent-care facilities, was climbing the charts. To push his new solo album, Always You and Me, Smith sought out a Nashville producer and promoter named Tony Mantor, who helped take his songs to radio. Mantor zeroed in on a clean-cut disco-pop tune called “You’re My Kind of Beautiful.” Alternately punchy and sultry, it finds Smith straining for a Bee Gees-esque falsetto as he croons Lothario-lite lyrics: “A Hollywood smile with a New York style/Those seductive eyes, they’ve got me hypnotized.”

Mantor’s instincts were correct. “You’re My Kind of Beautiful” enjoyed 13 weeks on two adult-contemporary radio charts, one run by Billboard and the other by Mediabase, which tracks radio airplay. Nestled among hits by the Chainsmokers, Bruno Mars, Ariana Grande, and John Legend, Smith’s song peaked at Number 35 on Billboard and Number 33 on Mediabase.

To qualify for these two so-called monitored charts, among the most precise in the industry, Mantor sent a specially encoded version of “You’re My Kind of Beautiful” to stations that allowed each chart to track exactly when and how often the song was played. “That’s the beauty of monitored,” Mantor says. “They can’t manipulate it.”

In a March 2017 Instagram post, Mantor celebrated Smith’s 12th week on the charts, calling it a “great way to start a career.” But Smith appears to have been looking for much more attention, much faster, on a system he could manipulate. Around the same time, according to a federal indictment, Smith started to use fake email addresses to create bot accounts on streaming platforms that could play his music on repeat.

In October of that year, federal prosecutors say, Smith emailed himself a “breakdown of how many streams he was generating each day and the corresponding royalty amounts.” He had 1,040 accounts, each one streaming approximately 636 songs a day. With his music accruing about 661,440 streams a day, and the average royalty per stream at half a cent, Smith estimated he was earning $3,307.20 a day, $99,216 a month, and over $1.2 million a year.

Between 2017 and 2024, prosecutors say, Smith had as many as 10,000 active bot accounts streaming his music. While Smith had a catalog of his own work, he also allegedly purchased and uploaded hundreds of thousands of songs generated with artificial intelligence. By the time he was indicted on fraud charges and arrested at his home outside of Charlotte, North Carolina, in September 2024, Smith had allegedly made more than $10 million from the scheme. (Smith has pleaded not guilty and denied the accusations. Through a lawyer, he declined to comment further on the specifics of the case, though he did respond to a detailed list of additional allegations described in this article.)

Smith is the first person in the United States to face criminal charges tied to streaming fraud, bringing him the name recognition he spent more than a decade chasing. Smith used his wealth — generated by business ventures including his medical facilities — to push an array of projects and forge surprisingly deep connections in the music industry. He collaborated with Juicy J, Nappy Roots, Cyhi the Prynce, DJ Whoo Kid, and Royce da 5’9”. The Avila Brothers, songwriters and producers best known for their work with Usher, recorded one of his songs with Billy Ray Cyrus and Snoop Dogg. Smith nearly persuaded RZA to let his record label release a new Wu-Tang Clan album. He even put up the money for a rap reality competition called One Shot, which aired on BET in 2016. By funding the project, Smith earned himself a seat at the judges’ table alongside RZA, T.I., and DJ Khaled.

Those who worked with Smith tend to remember him with a mix of amusement, bemusement, and occasional scorn. He was a competent musician, if not an especially talented one, yet his confidence was colossal. “He thought he was the best guitarist in the world, the best singer in the world,” says Jonathan Hay, a publicist who’d become Smith’s main creative partner during the 2010s.

Sabrina Kelly, who worked with Smith as a creative director and occasional vocalist in 2013 and 2014, says Smith had a childlike yearning for acceptance and approval. She compares him to Michael Scott, Steve Carell’s incessantly needy character on The Office.

“Mike is somewhat likable, but he’s very generic. Even his name is generic,” she says. “His songwriting was generic. His voice. Nothing stood out. He was savvy as a businessman, but that’s not what he wanted. He wanted to do music. He wanted to be in the limelight.”

“Money talks” and “Fake it till you make it” are classic music-biz maxims. But Smith’s alleged crimes show how they’ve been juiced in the streaming era with the internet’s promise of global reach and the almighty algorithm’s ability to make anyone famous, legitimately or not. Smith’s tracks appear to boast bot-assisted play counts in the millions, enough to generate solid royalties and suggest they might be the work of a star in the making. Meanwhile, those same bots were allegedly consuming Smith’s discography of AI slop. Fake streams of fake music generating real dollars, all of it further clogging the web’s backed-up, barely usable plumbing.

One of the internet’s greatest powers is its ability to warp reality and make the fake look real. Smith spent more than a decade gazing into that fun-house mirror. From data-driven angles, Smith resembled a rock star, even if nobody really knew who he was.

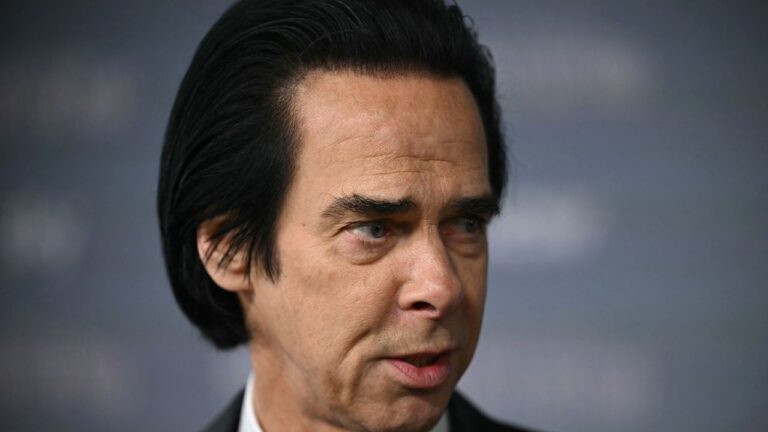

“Mike was a savvy businessman, but that’s not what he wanted,” says a former collaborator of Smith (shown here in 2015). “He wanted the limelight.”

Joshua Black Wilkins

Annual Losses in the Billions

Smith’s prosecution in the U.S. is part of a global rise in streaming-fraud cases. In 2024, a 53-year-old man was convicted of streaming fraud in Denmark and sentenced to 24 months in prison. In Brazil early last year, someone was accused of uploading more than 400 fake tracks to Spotify and generating over 28 million fake plays. But it’s difficult to determine just how widespread this activity is. A 2023 study in France found that between one and three percent of all streams there were fake. Beatdapp, a streaming-fraud-detection program, recently estimated at least 10 percent of all streams are fraudulent.

Fake streams are a scourge because of the way artists, songwriters, and rights holders are paid in the streaming era. In this “streamshare” model, subscription and ad dollars are pooled, and that money is allocated based on each artist’s share of total streams. Bot streams not only generate money for whomever’s behind them, but also leave less in the royalty pool for others. If the numbers in the French study held true globally, that would mean losses in royalties of up to $510 million. Beatdapp suggested annual losses could be between $2 billion and $3 billion.

Michael Lewan, executive director of the Music Fights Fraud Alliance, admits he hasn’t seen a “trusted percentage or number” on streaming fraud. But even a small one could mean significant losses: Music streaming generated $14.9 billion in revenue in the U.S. alone in 2024, according to the Recording Industry Association of America.

“If you view it as one or five or 10 percent — that is a percentage of royalties not going to artists, creators, and songwriters,” Lewan says. “It’s being extracted from the royalty pool in relatively large sums.”

When Smith was indicted, then-U.S. Attorney Damian Williams stressed streaming fraud’s impact, saying “Smith stole millions in royalties that should have been paid to musicians, songwriters, and other rights holders whose songs were legitimately streamed.”

But many working musicians already feel shortchanged by the streaming system Smith is accused of exploiting. Much of the money in the streamshare model goes to the most popular artists and biggest rights holders, leaving fractions of pennies for everyone else.

“He thought he was the best guitarist and best singer in the world. He really believed that.”

Beyond fake plays, streaming services are rife with activities that are technically above board, yet reek of someone gaming the system. In a bombshell book, journalist Liz Pelly recently exposed Spotify’s Perfect Fit Content program, an alleged internal effort to seed popular playlists with cheaply licensed music that would rack up millions of streams, siphon money from the royalty pool, and decrease how much Spotify had to pay out to other artists. While the tracks were often created by real musicians (who received flat fees and little to no royalties), they were frequently credited to nonexistent “ghost artists,” not unlike Smith’s own alleged trove of AI-generated tracks. (A Spotify spokesperson says, “Any claim that Spotify uses functional music to dilute artist royalties is false.” The company adds that playlist editors “program music based on what resonates positively with users,” and “no licensing agreement guarantees playlist placement.”)

And then there are the rumors and accusations that streaming fraud isn’t just the remit of low-level hustlers and scammers, but also takes place at the highest echelons of the music industry. Drake recently accused Universal Music Group, the largest major label, of conspiring to “artificially” boost the popularity of Kendrick Lamar’s “Not Like Us.” (UMG denied the charge, and the suit was dismissed.) Last November, a new class-action suit accused Spotify of “turn[ing] a blind eye” to “mass-scale fraudulent streaming” and suggested that Drake was the beneficiary of “billions” of fake streams. (A Spotify spokesperson says the company could not comment on pending litigation, but denied the platform benefited from artificial streams. Reps for Drake didn’t return a request for comment.)

This has lent Smith’s alleged crimes an air of the folk-heroic. Reddit threads about him are filled with jaded quips like, “So it’s OK for music companies to do it but not this guy?” But the allegations against Smith may be indicative of a long pattern of deceitful, self-absorbed behavior. Several people contacted for this story turned down interview requests, or agreed to speak only on background, because they wanted nothing to do with Smith ever again. Others who did speak relished the opportunity.

“I feel no shame saying this — maybe I should feel a little guilty, but I don’t,” says Othr Bestlasson, a former singer-songwriter who worked with Smith from 2013 to 2015. “I am so happy. Mike Smith was such an asshole.”

‘Someone Willing to Break Rules’

In an era of crypto rug-pullers and AI-slop scammers, one might expect the first person indicted in the U.S. on charges related to music-streaming fraud to fit the mold of a Gen Z operator: broccoli haircut and a leased Lamborghini, trips between Miami and Dubai, looking for the next online arbitrage opportunity. Even though he wanted to be a rock star, Mike Smith, 52 at the time of his arrest, sometimes let his dark hair fade to gray and a peppery stubble sprout on his face. In his mug shot, he looks wide-eyed and weary.

Born in Philadelphia and raised largely in northern New Jersey, Smith started to play music at age four. He began on guitar before teaching himself bass, drums, and piano. Coming of age in the Eighties, he leaned toward hard rock, hair metal, and their predecessors: Guns N’ Roses and the Rolling Stones, Kiss and Led Zeppelin.

In a 2016 book — a self-help tract-cum-memoir called Lovin’ Each Day — Smith wrote that his mother left the family when he was eight or nine; at 10, one person close to Smith says, he wrote his first song, called “Standing in the Darkness.” Smith wrote little else about his mom, but once stated that she hailed from Havana. (In the same sentence, Smith claimed he was related, somehow, to Fidel Castro. Smith says he heard this from his mother and grandmother.)

“He wanted so bad for people to look at him and go, ‘What a wonderful musician you are!’”

Smith says his father sold chemicals for a living, and according to his book, his dad’s life revolved around work. “He never did anything that really made him happy,” he wrote in Lovin’ Each Day. “He just did what he thought he had to do to support a family.… He had a quiet misery to him.”

In high school, Smith played in several hard-rock bands with names like Self Destruct, Silent Scream, and Outrage, and claimed to have opened small local shows for Blues Traveler and Warrant. But music grew peripheral as he got older. He studied finance at the University of North Carolina Greensboro and stayed in the state after graduating. Per his memoir, he made his first chunk of money off the Y2K scare. Though he had no tech background, Smith taught himself to code and “designed a little scan tool” that would address the calendar problems people feared would erupt on Jan. 1, 2000. Smith’s company, New Millennium Technologies, was soon an IBM business partner, handling remediation and Y2K testing for clients.

In explaining how he funded this venture, Smith wrote in his book, “I don’t recommend that you do this,” before revealing that he applied for 20 credit cards, took money off half of them, then paid down his seed money with the one percent he got back each time he did a balance transfer.

Responding to this passage, Katherine Reilly, a former prosecutor who worked on the Smith case, says, “The way he got his business off the ground has all the hallmarks of someone who is willing to bend — and ultimately break — the rules to get what he wants.”

Over the next few years, Smith got married, had two kids, and embarked on various business ventures. His book mentions a software company and a “failed business” that nearly ruined him in the early 2000s (public records show Smith filed for bankruptcy in 2002). By 2008, his “financial situation had improved greatly,” but Smith also wrote that he was “overweight,” “unhappy” with his job and marriage, and “relatively disengaged” from his children. A divorce soon followed.

Reuniting with and marrying Erika, his college sweetheart, reignited Smith’s “musical passion.” He quickly wrote and recorded an album documenting this period called Love Interrupted, which he self-released in 2013.

Not long after, Smith connected with Hay, the music publicist. Hay wasn’t a big shot, but he had a reputation. In 2004, Hay claimed one of the producers of Rihanna’s “Pon de Replay” hired him to gin up attention for the song, which he did by planting a fake rumor in the tabloids that Rihanna was having an affair with Jay-Z. (The producer denied hiring Hay, as did Rihanna’s lawyers; Hay later apologized for his role in the scandal.)

Smith and Hay were made for each other: hustlers with dollar signs in their eyes and huge musical ambitions. Hay had connections, the know-how to generate more, and ideas for making it big. Smith had the money to — maybe — make it happen.

“In the beginning, it was wonderful,” Hay tells Rolling Stone. “But Mike had such deep pockets that even though we were partners, his decision always reigned over mine.”

‘This Guy’s Fake as Fuck’

Smith and Hay started a record label, SMH Records, in October 2013 and claimed to have raised $30 million. SMH was described as a partnership between Hay’s publicity firm and Smith’s Rogue Entertainment, a company that purportedly owned “numerous businesses … including a chain of medical practices across North Carolina and Tennessee.” These medical practices — which would later garner scrutiny from prosecutors — appear to have been the primary source of Smith’s income.

The label’s prospects were promising: It inked a distribution deal with Caroline, a Capitol Records subsidiary, and Smith and Hay persuaded a veteran Universal Music exec to leave a senior vice president post to serve as chief operating officer. SMH had the budget and staff to find and develop new artists, but Hay says he also had to keep Smith happy. One of the first songs Smith sent Hay was “Whiskey Woman,” a Southern rock/country track Hay describes as “so bad” and “very dated.” He instead nudged Smith toward hip-hop in the mold of Everlast, the House of Pain rapper who scored a few hits with rootsy rap-rock in the late Nineties and early 2000s.

The other part of their strategy was simple: “Pay all these different major artists to feature on our music and build our name,” Hay says. Smith and Hay spearheaded two albums together: Fear of a Pink Planet, credited to a group called Pink Grenade, and When Music Worlds Collide, credited to Smith, Hay, and the Bay Area hip-hop stalwart DJ King Tech. Both albums were stuffed with features: Kxng Crooked, Inspectah Deck, Royce da 5’9”, and Parliament-Funkadelic drummer Jerome Brailey, among others. Even Johnny Depp had an uncredited monologue on one song.

Pink Grenade was Smith and Hay’s first big gambit. The group comprised nine people, most referred to anonymously and wearing hot-pink balaclavas, including Smith, who used the moniker Mekai. In a press release, where Smith is credited as co-founder and executive producer, he insisted that Pink Grenade’s focus on anonymity was about putting “the team first, not the individual.”

Pink Grenade, one of the first groups formed by Smith, in which members were largely anonymous and wore hot-pink balaclavas

Courtesy of Sabrina Kelly

One of those individuals was Bestlasson, a struggling guitarist and singer-songwriter who had battled addiction before getting clean. When he connected with Smith and Hay, he was cautious but intrigued by their contacts. His hopes evaporated quickly.

“From the first moment I met him,” Bestlasson says of Smith, “I was like, ‘Oh, my God, this guy’s fake as fuck.’”

Bestlasson remembers Smith as quick to anger, easily frustrated, and averse to receiving constructive criticism. “He wanted so bad for people to look at him and go, ‘What a wonderful musician you are!’” Bestlasson says. The guitarist and vocalist appeared on several SMH releases, but claims Smith tried to undercut him on his rightful share of publishing royalties. (Noell Tin, Smith’s lawyer, says Bestlasson was “paid according to the terms of a revenue-sharing agreement.”) Frustrated with the haggling, Bestlasson threw up his hands and left the band.

Hay says Smith put barriers between himself and those he worked with. He recalls one of Smith’s closest associates, who was involved in both the music and medical clinics, and did whatever Smith asked. “Mike treated him like shit,” Hay says. “He would cut Mike’s steak for him.” Kelly remembers this same person picking the cucumbers out of Smith’s salad. (“Mike has never had anyone cut his steak or pick cucumbers out of salads,” Tin says.)

Crooked’s memories are more charitable. He says Smith “kept his word” in money matters and was open to criticism, especially when it came to hip-hop. “He respected the opinion of people who had experience,” Crooked says. Smith was always eager to get in the studio and create, too, and whenever he talked about music, Crooked adds, “it was like that inner child coming out.”

‘He Wanted to Be the Star’

Reilly, who is now a partner at the law firm Pryor Cashman, was a prosecutor in the U.S. attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York when the Smith investigation began (she declined to say when that was). As the head of the Complex Frauds and Cybercrime Unit, she saw familiar patterns in Smith’s case, even if charges tied to streaming fraud were novel.

“The allegations suggest this is an individual who identified a pot of money … and developed a way to give himself access to [it],” she says. “Along the way, he was alleged to have made a variety of misrepresentations to people who asked questions to allow his scheme to continue. That is the fact pattern of every financial-fraud case.”

But streaming fraud is unique in that money isn’t always the only, or even the original, motivating factor. For someone like Smith, delusions of grandeur can be found in the most fleeting of places — like the view count on a YouTube video. Kelly remembers witnessing a moment between Smith and his wife at their lakeside home around 2014: “He was obsessing over comments on one of his videos,” she recalls. “But when you looked, it was clearly fake [comments] that he paid for. He’s reading them out loud, like, ‘Oh, my gosh, I have fans!’ His wife seemed convinced that he was becoming this big star.” (Smith declined to address the allegation, but said he “disagrees with the vast majority of accusations made by Jonathan and Sabrina.”)

That same year, Pink Grenade dropped their sole album, Fear of a Pink Planet. To attract attention, the group released a music video for a song called “Let’s Take It Naked” stuffed with over-the-top debauchery, including people doing cocaine off a fake-pregnant woman’s belly. A video for “Lipstick” — a song that takes lyrical jabs at Kim Kardashian — features Ashlee Holmes, then a fixture on The Real Housewives of New Jersey.

At a glance, it might’ve seemed like these headline-thirsty schemes were working. Both “Lipstick” and “Let’s Take It Naked” were pushed on the popular viral-video aggregator and incubator WorldStarHipHop, garnering more than 5 million views each. Yet both videos received only a few hundred comments, most of which were overwhelmingly negative. (For example: “Lmaoo SMH records? That’s exactly what I was doing listening to this corny shit SMH,” wrote one commenter, playing on the acronym for “shaking my head.”)

Jacorey Barkley, who worked at SMH Records as a college intern, says Pink Grenade’s numbers “never made sense” to him. In a summer dominated by viral hits like Rae Sremmurd’s “No Flex Zone” and Bobby Shmurda’s “Hot N*gga,” Pink Grenade “didn’t feel like the other million-view things” he saw online. Nor did it pass the all-important test: “If you see something on the internet and then you hear it in real life, that’s when you know shit’s moving.… If they’d gotten a million views organically on WorldStar, we would’ve been meeting with every fucking label.”

Hay insists “everybody was contacting us” about the music, though Kelly disputes this. Still, both agree the attention wasn’t to Smith’s liking. The group was garnering all the buzz, and Smith, Hay claims, “wanted to be the star.” Soon, Smith would get his chance when Crooked floated the idea of a hip-hop reality competition.

An ‘Odd Duck’ Gets His Break

One Shot was announced at the end of 2014 and was made with no network attached and Smith bankrolling the whole thing. Still, Smith and his main collaborators — Crooked, King Tech, and radio personality Sway Calloway — were able to hold nationwide auditions and tap T.I., RZA, the Game, Tech N9ne, Twista, and DJ Khaled as guest judges. Crooked says they filmed nearly 80 percent of the show themselves, used that footage to create a sizzle reel, and sold it to BET before completing production. For the winner, One Shot promised $100,000 and a deal with SMH.

T.I., DJ King Tech, Kxng Crooked, and Smith (from left) at auditions for the reality competition One Shot

Courtesy of Sabrina Kelly

Holding an acoustic guitar in a 2016 interview, Smith described himself as the “odd duck” on One Shot, the self-proclaimed “guy who writes country songs.” What he brought to the show, he insisted, was an eye for talent: “I’m looking at it purely as an artist: What’s their songwriting capability? What’s their ability to actually be a star?” (He also claimed to have 5,000 songs he’d written stored on his phone.)

Kim Osorio, a former editor-in-chief of the hip-hop magazine The Source, was a consulting producer on One Shot and remembers that, behind the scenes, folks found Smith’s prominent role perplexing. But, she says, “we were getting paid. So if this guy wants to be the don dada of rap stars, no one really cared.”

Crooked says there was some concern about Smith serving as a judge, but he credits Smith for learning on the job. “He talked to the artists and handled a lot of things,” Crooked says. “His business acumen was on point.”

After so many haphazard projects with Smith, Kelly was shocked at how professional the One Shot production looked. At a club in Charlotte, the lights were on, the cameras were rolling, and a line of hopeful contestants stretched down the block. The spotlight lent Smith new legitimacy, Kelly says, and also changed him. “The closer people get to fame, the weirder they get,” she says.

Hay and Kelly broke with Smith in early 2015, around the time production on One Shot began. That January, the pair agreed to sell their shares of SMH back to Smith for $100,000, with an initial payment of $40,000, which was sent in increments via PayPal from an account linked to one of Smith’s medical clinics. Within a month, though, the situation had deteriorated. In late February, Hay sent various associates a document accusing Smith of financial malfeasance and suggesting he was not as rich as he claimed. Hay says he cc’d Smith, who replied-all: “You got a tiny penis.”

Hay and Kelly, independent of each other, claimed that Smith reversed the $40,000 payments. They filed a dispute with PayPal, but had little luck recovering the funds. Smith, through his lawyer, said the payments were reversed after Hay broke a non-disparagement clause by sending the document in the first place. Tin, Smith’s lawyer, also shared an email Hay sent to Smith and two of his family members in April 2015, in which Hay admitted, “I really believed Michael was doing horrible things behind my back. He wasn’t. That’s embarrassing to admit, but I was fighting a monster that was really a fantasy — believing things a few others had told me, but mostly it was my own fault.”

(Hay, in an email, claims Smith manipulated him into sending the mea culpa: “I was gaslit by an expert. He held my career and our unreleased music … over my head, making empty promises of promotion and payments to secure my silence and that apology.”)

But behind all of this drama and chaos, the federal government was also digging into Smith’s finances. In late 2015 and early 2016, Smith and his company Carolina Comprehensive Health Network were accused of Medicare and Medicaid fraud in two separate lawsuits. Suing on behalf of the government, whistleblowers at some of his clinics alleged that they were instructed to carry out tests and procedures that were “not medically necessary” and then submit false reimbursement claims. One of the two complaints alleged that SMH directly benefited from this fraud. By September 2015 — well into production on One Shot — Carolina Comprehensive Health Network had allegedly paid SMH $150,000.

Smith and his co-defendants denied the allegations, and their legal battle dragged on for several years. In September 2020, Smith settled one of the fraud cases for $900,000, while the other was dismissed.

None of this had any impact on One Shot, which eventually premiered on BET in August 2016. The winner was a Charlotte rapper named Three.

During auditions, Smith promised that the $100,000 prize would be its own reward, separate from the SMH deal also on the table. “That’s just straight cash to [the winner],” Smith told the hip-hop outlet ThisIs50 at auditions in Miami. “No strings attached.… It’s not part of the record deal or anything.” But after the show sold, the contestants who made the final rounds were asked to sign a new artist agreement, approved by the One Shot partners and mandated by BET, per Smith’s lawyer. Unlike the original “no strings attached” promise, the contract stipulated that the $100,000 would be “an approved recording fund” for an “initial album.”

RZA on the set of One Shot.

Smith with Kxng Crooked (left) and Hay at a 2014 meeting in Detroit

Three never recorded an album for SMH. He released one single, “Payoff,” through the label. Asked if Three received the $100,000 prize, Smith’s lawyer referred to the artist agreement and said, “Three was paid what the parties agreed to.”

According to Crooked, Three and Smith fell out after One Shot, but Smith’s lawyer denies this: “The relationship ended amicably, and Mike has nothing but good feelings toward Three.” Three, who would go on to release several albums through other labels, declined multiple interview requests for this article. In a 2024 interview, he said he’d endured “too many fucked-up deals” in his career “not to be on my business.”

‘No Fraud Going On!’

Two years after their fallout, in 2017, Smith and Hay reconciled. Smith was adamant they get back in the studio and had a new plan: If they made their tunes jazzier, they could qualify for the Billboard jazz charts, which were far easier to crack than the hip-hop charts.

In the fall of 2017, they released an album, Jazz, and after it floundered, tried again in 2018 with an updated version, Jazz (Deluxe). This time, they hit Number One on Billboard’s Jazz and Contemporary Jazz Albums charts. Smith was elated: “I can’t believe this!!!” he wrote on Instagram. “I officially have a Number 1 Billboard Album!!!! Incredibly grateful to everyone out there for your support.”

Smith finally seemed poised for a breakout moment. After the success of Jazz (Deluxe), his solo music saw traction too. In June 2018, he shared a photo of his Spotify stats on Instagram, showing 214,875 monthly listeners and more than 72,000 listeners that day. “That’s crazy and thanks to everyone who listens,” he wrote. “Truly grateful!”

More hits followed. A sequel, Jazz Part Two, credited to Smith, Hay, and King Tech, topped the Contemporary Jazz chart in July 2019, and hit Number Two on the Jazz chart. And Follow the Leader — an instrumental reimagining of Eric B. and Rakim’s classic album of the same name — topped both charts the following month.

But success was short-lived: After one week, most of Smith’s albums often fell precipitously down, or off the charts entirely.

In 2018, the indictment notes, an unnamed distribution company twice flagged Smith’s music for potential fraud, to which Smith replied in an email: “There is absolutely no fraud going on whatsoever!” The following year, another flag arrived. Smith again insisted he’d done “NOTHING to artificially inflate the streams on my two albums.”

But the same month that he fired off that first vociferous denial to the distributor, Smith allegedly reached out to two unidentified people with an idea: “In order not to raise any issues with the powers that be we need a TON of content with small amounts of Streams.” Two months later, he wrote, “We need to get a TON of songs fast to make this work around the anti fraud policies these guys are all using now.”

As prosecutors suggest in their indictment, Smith had figured out a key flaw in his alleged scheme. A billion fake streams for one song would “raise suspicions,” but “a billion fake streams spread across tens of thousands of songs … would be more difficult to detect.” AI-generated music, still a relatively new phenomenon in 2018, offered a potential solution. The indictment says Smith began working with the CEO of an AI-music startup, believed to be Alex Mitchell of Boomy, to create “hundreds of thousands of songs using artificial intelligence.” Mitchell isn’t named in the indictment and hasn’t been charged with a crime in the case (nor has Boomy), but he’s believed to be unnamed “Coconspirator 3” based on publicly available publishing information that lists him as a co-writer on some of the tracks named in the indictment.

Smith with musical collaborators at his home studio in 2015

Courtesy of Sabrina Kelly

Boomy did not return a request for comment. In a statement shared with Billboard in 2024, Mitchell denied any wrongdoing, but not an association with Smith: “We were shocked by the details in the recently filed indictment of Michael Smith, which we are reviewing. Michael Smith consistently represented himself as legitimate.”

Smith’s indictment primarily focuses on the AI tracks, and it’s likely that much of the $10 million in royalties he’s accused of making came from this prong of the scheme. Those songs have largely been scrubbed, but much of the music Smith released under his own name is still widely available.

A version of “You’re My Kind of Beautiful” uploaded in 2024 (seven years after it cracked those Top 40 airplay charts) has more than 7 million streams on Spotify. The song “Hardworking Man,” a bro-country stomper in which Smith rhymes “blue collar” with “dollar” and “holler” in a put-on Southern drawl, has a million views on YouTube. (A version by Snoop Dogg, Billy Ray Cyrus, and the Avila Brothers has just 405,000 views in comparison.) Another collab with Snoop Dogg, 2024’s “Take Me to the Edge,” currently has more than 16 million views on YouTube, with fewer than 700 comments.

Smith also allegedly tried to “sell” this scheme as “a service” to other musicians, according to the indictment. One musician tells Rolling Stone that Smith and an associate approached him with an offer and a “guarantee” that they could net him $2,000 a month from his catalog. The musician, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution, looked at a contract, but never signed it.

“I thought it was shady from the get-go,” he says, before noting that Smith’s associate reneged on the deal a few days later. “Without saying it, he basically was like, ‘Yeah, we kind of got busted, and this is not really legit.’” (The associate did not reply to multiple requests for comment.)

All the while, Hay claims, he was trying to raise alarm bells. He learned about the fraud warnings Smith was receiving in late 2018 and, by the end of the following year, was sending impassioned emails to distributors and journalists, insisting Smith was engaged in a massive fraud scheme. He says he contacted the FBI, too, and even tried to persuade Billboard to fix its charts and remove Smith’s five Number One albums (Hay was credited on four of those). But like his attempts to expose Smith during One Shot, these efforts fell flat.

(“In circumstances where Billboard receives credible information that published data is not accurate within a reasonable time frame after a chart is announced, Billboard will make appropriate adjustments based on restated data,” a representative for Billboard said in a statement. Billboard and Rolling Stone are owned by the same parent company, Penske Media Corp. A spokesperson for the FBI declined to comment.)

Hay isn’t named in the indictment and has not been charged with any crime, but appears to be “Coconspirator 2,” identified as a “publicist” whose music catalog Smith allegedly used early on in his scheme. “Technically, I couldn’t say 100 percent, right?” Hay says. “But it does seem that way.”

In 2023, according to the indictment, the Mechanical Licensing Collective — a nonprofit that helps track and distribute digital publishing royalties — “confronted Smith about his fraud.” The indictment notes that Smith, through his representatives, denied the allegations, but the MLC still “halted royalty payments.”

But money could have still flowed to Smith from other sources, including two different types of royalties generated by the sound recordings, and another publishing royalty that would have been paid out through a performing-rights organization like ASCAP, BMI, or SESAC. “No one has figured out [what channels] that $10 million went [through],” says one music-industry source.

So who paid Smith? The indictment says he fraudulently inflated his streams on platforms like Amazon Music, Apple Music, Spotify, and YouTube Music, though there have been reports that Smith’s music also popped up on SoundCloud, Pandora, Tidal, and even Boomplay, a popular streaming service in Africa. Spotify, in a statement, said its preventive measures caught Smith early, minimizing the royalties it paid out — just $60,000 — for Smith’s own music and the AI-generated tracks. Pandora similarly said it only paid out $1,500 in royalties to Smith. SoundCloud would not say if, or how much, it paid Smith, but touted the efficacy of its “fan-powered” royalty model, which boasts a set per-stream rate to ensure royalties go directly to artists that people listen to.

“No pooled royalties mean bots have little influence, which leads to more money being paid out on legitimate fan activity,” a SoundCloud rep told Rolling Stone.

Hay alleges that most of the money came from Tidal: “Mike’s thing was Tidal.… And Tidal paid the most, but they would only pay you like once or twice a year.” (“We don’t address speculative claims,” a rep for Tidal says.)

Smith’s case illustrates just how vulnerable music streaming is to fraud. Access to the kinds of bots capable of artificially inflating streams to serious moneymaking levels is easy to come by, whether on Discord channels, subreddits, specialized hacker forums, or the dark web. Yes, there are guardrails, and companies like Beatdapp offer tools to combat streaming fraud, but there are also weak points in the system. Every time a fraudster sends a bunch of tracks to a distributor to upload to streaming services, that company gets a cut; performance-rights management companies also take a percentage, no matter how those royalties are generated.

“Almost every player in the market has their own incentives, and those incentives don’t always align with preventing this type of activity,” the music-industry source says.

Lewan, of the Music Fights Fraud Alliance, argues that plugging these gaps means looking at streaming fraud not just in terms of lost dollars but also lost trust. He says Smith’s indictment “sent a clear signal to the industry that they need to take fraud seriously” and start “building a more mature anti-fraud ecosystem” to prevent similar cases. “All that stuff ultimately undermines the trust and integrity that users and listeners and creators have in the digital marketplace.”

Reilly, the former prosecutor, adds that a successful prosecution of Smith could help address these issues. “I think it will make those who play a role in the system, and maybe stand to benefit if there’s fraud, pay attention in a different way,” she says. “They might before have said, ‘Is this against the terms of service? Maybe. But that’s not really our problem.’ But if you’re assisting in criminal conduct, that is your problem.”

In the era of streaming and social media, it’s long been suspected that labels are “juicing the numbers” and “using bots” to boost streams, affirms Crooked. Whether or not that’s true, Crooked says, if people believe it, they’re going to say, “Yeah, Mike! Screw the system.”

“Whatever he did, he made that bed and he’s got to lie in it,” he adds. “But to crucify him means, in my mind, go crucify Warner, go crucify Universal, go crucify Sony. Let’s not take the man who’s the independent guy [and] string him up.”

SINCE HIS ARREST IN 2024, Smith has been out on bail as his case moves through the courts. His trial is expected to start on Oct. 6. (If convicted, Smith faces a maximum of 60 years in prison.)

Barkley, the former SMH intern who went on to work at Def Jam and started his own marketing agency, Contraband, says he sees so many young artists “that are in danger of becoming what Mike became … of building this fake career and believing it.”

Smith’s capacity for believing it could be staggering. But a sincere streak courses through his irrepressible confidence. When reached for comment about claims that he exaggerated his musical abilities, Smith sent a Dropbox folder with 18 videos as evidence to the contrary. Thirteen were filmed in early 2026 at his home, one a full tour of his studio, an attic-like room festooned with guitars and keyboards. In the other 12, Smith excitedly flaunts his prowess on individual instruments: piano, drums, bass, and a variety of guitars and other stringed instruments, including banjo, dobro, and mandolin.

“OK!” he says in one clip with a big grin and a slight chuckle. “I don’t play dulcimer much these days” — pronouncing it DUL-chimer — “but here we go.” For about 30 seconds, he sweeps the strings with his right hand and carefully moves his left index finger around the fretboard. It’s passable, charming even, as he draws out the instrument’s bright, serene drone. Smith wanted to be heard, so badly he allegedly made it look like millions were listening. But you can see him spending hours playing for no one but himself.