Phish bassist Mike Gordon was always in awe of Bob Weir, from seeing him perform onstage as a kid to decades later staying at his home in Hawaii with Bob’s family. As the youngest member of his own band, Gordon often felt a kinship with Weir, “the Kid” in the Grateful Dead. He spoke to Rolling Stone while in Woodstock preparing for his spring solo tour, and recalls their time together at TRI Studios working on flow-state experiments, the time he almost joined Dead & Company, and Bob sitting in with his band.

Honestly, everything about Bob Weir was dichotomies. Interesting dichotomies for me, from my perspective. Watching him as a kid, he seemed to be the one [in the Grateful Dead] that was the real rock star type. Just a bit self-conscious, and sometimes the hair flicking and all that. His playing, on the other hand, seems really selfless, because it just weaves into the music almost unnoticeably, and yet it’s so eloquent. But his personality had that combination of those kinds of things, like seeming super-cold because he didn’t smile that much. He was actually one of the warmest people ever.

I mean, it’s not often that I meet a hero of mine, some rock star, and then just have him write his phone number down for me, not really knowing me. And then staying in touch over the years and always responding. And yet, playing in different groups with him, he’s also never the one that would give out compliments. Like, “Nice drum solo” or “Nice bass line.” Ever.

He could be stoic, and then he would say something that was really funny. And the fact that he really lived life hard, but then later in life [was very healthy] — one of those last experiences was going to his beach house, where he had me do his meditation with him, guided meditation, and going for a run and doing other workout parts, eating all vegan food. Everything about him was a daily routine of health, after daily routines of raging, probably. So I don’t know if he always had these splits or if I just noticed them as time went on.

I worked out with him. He did it with a lot of people. We did a guided meditation, based on what I do, Transcendental Meditation, but a little different. And then he goes running barefoot. He would run barefoot on pavement or rocky mountains or the beach or anywhere, and his feet were kind of calloused, and I wasn’t going to do that. He kind of combined the meditation with the run. It was like a brisk walk or slow run, and he kind of repeated his mantra. In his backyard at his beach house there was a sandbox with 100 different kinds of fun workout things. He had the TRX straps, had these little videos of us doing push-ups into the air, leaning over the TRX straps. We had this twisting move. It looks like a samurai or something, where the legs and arms are all twisting one way and then all the way around the other way. He tried to show me and I just couldn’t do it, after about 10 minutes of trying to videotape everything, he’s like, “How about I’ll just do it and you videotape me.” So we did that. He had this heavy leather ball, and he wanted to do this thing where we just threw it back and forth, hard to launch and hard to catch, all in that sandbox with really nice tropical plants around it. Then he made me some vegan sausages. I know he’s always done yoga, over the years, and just seemed really healthy.

The reason we went to the beach house together is because we were at a studio doing this brainwave experiment. I read an article where he said dreams informed his whole life. His creativity, and the music that he writes, all informed by dreams. And I thought, “Oh, well, me too.” I had this team of neurologists, and one neurologist from MIT could get people in half-awake, half-dreaming, half-asleep. Bobby started coming on those Zooms [with the neurologists] and told us this one dream that he’d had. In it he said he saw his own band, he’s playing, but from 20 feet behind the stage and there’s someone younger that’s replaced him. Like a ghost. And he’s behind the drum set and he sees the new younger him. That was the middle of just a Zoom about neurological stuff, and then he offers up that dream. We were in his studio and we were wired up with the brain wave and body metrics and we had these two little buttons that we could push to indicate when one of us thought we were in or just had been in a flow state. Three other people in the room were also wired up and also had the button to push, and we wanted to see if we were pushing the button at the same time. And sometimes we were.

All of that was done. I had had a little bit of gummy something or chocolate, something with THC, maybe a little bit of mushrooms. I was really kind of out of my head, floating a little bit, because I don’t do much of that stuff. Then he and [his wife] Natascha invited me up for a vegan meal, and after he invited me to go to the beach house. They warned me that no one gets in the car, his kids don’t get in the car with him. He’s taking these switchbacks at 60 miles an hour in his Tesla going to Stinson Beach. I get motion-sick real easily, and I’m out of my mind a little bit because I’m floaty, and he starts telling stories. He just loved telling these funny stories from back in the day. So many stories. So that made up for the nausea. And I’m just being a good listener and I’m a little scared. We get to the top of the switchbacks, top of the mountain, he’s like, “Oh, I left my laptop back at home.” So then we repeat the whole thing, we get the laptop, we go back. One of the stories was about beating Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. I bet he’s told it before, but just in case…

So he’s underage, maybe he’s like 17 years old. It’s a club where you have to be of drinking age to get in, and he wants to meet Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. He goes around the back and there’s a ladder where you can climb up to the roof. He’s going to sneak in the club, and now he’s on the roof and there’s a skylight and he’s sort of investigating the skylight and he just crashes through all the way, falling down, and landing on a couch, which happens to be the green room, where he’s sitting next to Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. And he says, “Oh hi, I’m Bobby.” And from that point on, they’re best friends for the rest of their lives. Those kinds of stories are priceless. And I don’t care if I’m a little nauseous and a little scared and a little floaty.

He believed that digital music was ruining music, that it was unlistenable and made it so people couldn’t discover as many kinds of music. So in his little lair there, he had this tube stereo, turntable, speakers, and a big, huge daybed for listening to music. He put on some records, a country singer I had never heard of. It was a whole different experience listening to all that analog sound. Then he had all these guitars sprinkled about, and he was able to just work on his next album all by himself with this little recording station and some effects pedals and wireless thing on his guitar. He was like a one-man show. He could cook what he needed. I mean, being that level of rock star, you could easily have some chefs around, but he didn’t need any of it. He didn’t have a trainer, at that moment anyway. He didn’t have a chef and he didn’t have someone recording him for his album. He was very excited to show it off, how he could do it all by himself. My daughter and I went back to the beach house to visit him last year, which would’ve been two years later, and he was still working on the same album.

Our relationship was incredibly special, because I was a huge fan. There’s some friends that preferred the Jerry Garcia-written songs. I leaned toward the Bobby ones. I really liked the way he delivered a song, and he talked about that. In groups of people, a bunch of people that are doing a gig together, he would stop them and he would say, “Look, the singing is the face of the song. Everything serves that.” And he really delivered a story with his voice, and it’s so inspiring. I know he told Trey [Anastasio] when they were reviewing every Grateful Dead song ever before the Fare Thee Well concerts, they spent a week in their pajamas in that beach house, and he told Trey, “I know that we’re known for our jamming and everything, but really it’s mostly about the soulfulness of these songs.”

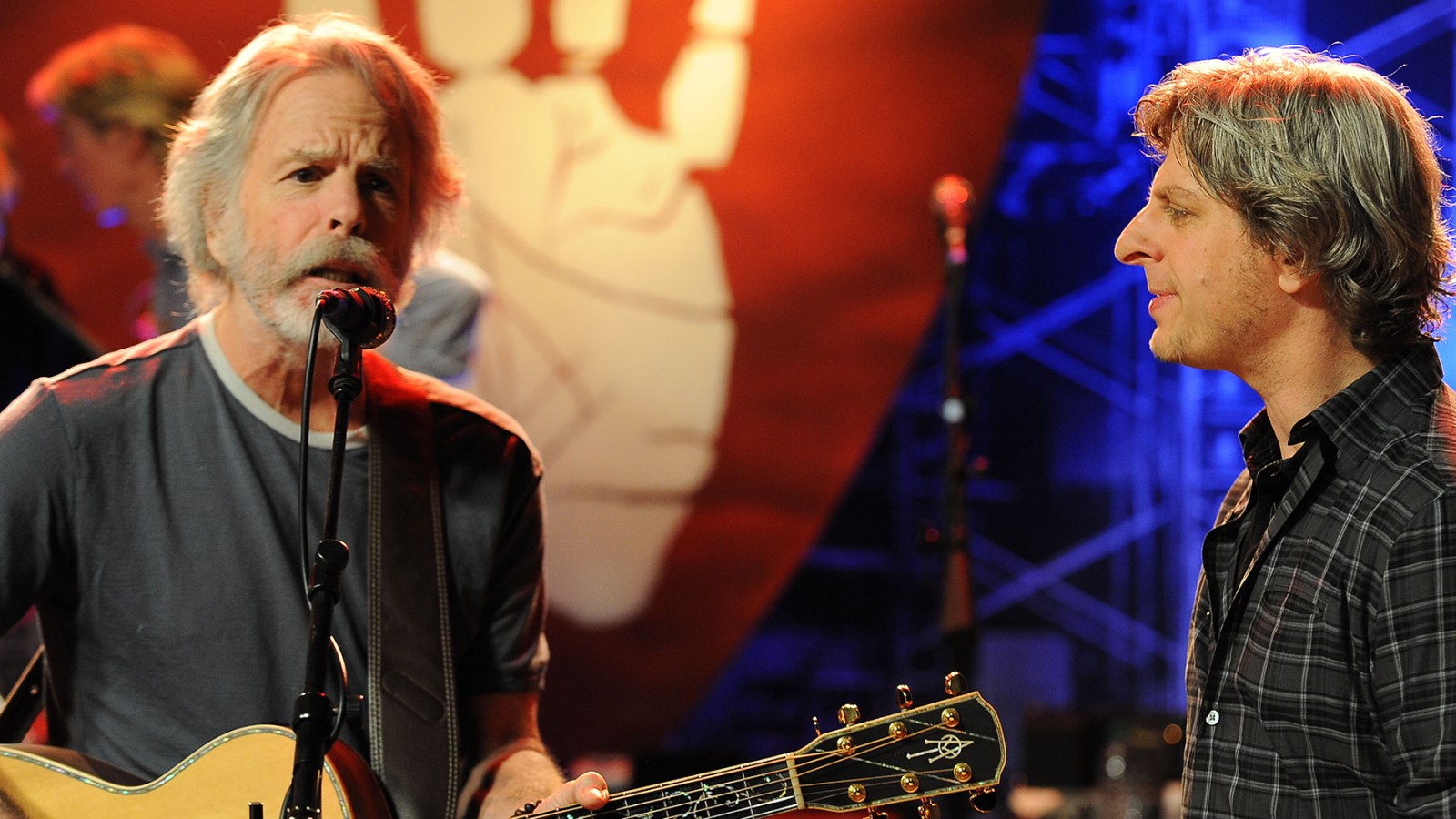

I was with the Rhythm Devils with Grateful Dead drummers, and all the other people playing at this festival, maybe Gathering of the Vibes. Bobby was there with one of his bands, maybe RatDog. The way that it worked is there were two stages so the bands could go back and forth. Bob had this idea, since I had been singing “The Other One” with that group, a few songs like that — maybe he would sit in with us, and I would sing the first [verse] or two, and their band would start and he would just continue where we left off, and he would sing the next verse with his band.

We’re on the tour bus and we’re trying to do a practice of this, and I’ve got my little practice bass and everyone’s looking at me. They’re all looking at me, and Bobby’s right there, my hero, looking at me, and I can’t for the life of me remember, after singing it all tour, the first or second verse to “The Other One.” Like “‘Spanish lady….’ What is it?” And Bobby’s looking at me with his deadpan face, not offering a smile or “It’s funny that you can’t remember this.” This is after being a kid and going to see him, and there I am singing it to him and unable to remember more than the first two words. Then to make it more awkward, one of the other singers is Googling for me, and they’re like, “Here, I’m finding it online.” And Bobby’s just not flinching. He is like, “I’m not going to help him. I’m not going to laugh at him, but I’m not going to help him either. I’m just going to stare at him.” It’s so embarrassing, but funny.

Bob did ask me to be a part of Dead & Co. He gave me a call and he said he has got something going with John Mayer. When he first was calling he had some other ideas, which morphed back to being more normal. He was imagining this show that would start all-acoustic every night, and then would go electric, and then would turn over to rave. Where it was just like beats and Grateful Dead songs, which I’ve heard people do before. That eventually turned into a [more] normal situation. I went out for one week of practice, I learned really interesting things from that experience. We were talking about having grooves that are swung and straight, half swung and half straight. And he said, “That’s what rock & roll is. Rock means the straight, and roll means the swung.”

Bob wanted to do more and different things. That was cool, but then I started to realize it was going to be a longer-term thing. I had my own album and I was making a Phish album, and they were starting to talk about doing some writing and making an album, too. I started to realize that getting to play with my heroes here is not going to match seeing through my own album.

Bob was one of the few guests Phish has had onstage. We had already played with Phil Lesh at Shoreline the year earlier. I remember I got this feeling from the band, or a message from the rest of Phish, that we weren’t going to have him play, because we just don’t have guests. As legendary as they are, it changes the flow that we get into. And so he called and he said, “Well, I’m just going to get a ride in. My driver will bring me in and I’m just going to bring a little amp and guitar, and what time is soundcheck?” It’s like, “Well,” I said, “I’m not really sure if the guys want to have any guests, but this sound check’s at 3:30.” And then more talking backstage of, “I don’t know. He’s great, but we don’t really have guests and there’s a reason for that. It’s really hard and tender to get our flow going that we have.” And Page [McConnell]is sitting backstage with him in one of the dressing rooms explaining that. And he’s like, “That’s OK.” And I ran into Trey outside of the dressing room and he’s like, “Oh, my God, I just talked to him. He’s friggin Bob Weir.” So I went back and so they figured it all out. I got to choose the songs. I remember there was “El Paso” and we did “West L.A. Fadeaway,” and then he played on “Chalkdust Torture.” He was nervous about that, like he didn’t really want to do it because he didn’t know it so well. It’s fast and frenetic and he’s slow sometimes. The guys, Jon Fishman describes it as the best sit-in ever. That even though he was a fish out of water, that he went for it. He just dug his soul into it and raged in the situation, even being out of his comfort zone.

Bob was so mysterious. I just thought it was incredible the way his rhythm guitar playing ebbed and flowed. When people heard Jerry Garcia’s guitar playing, it sounds like a bird fluttering. It’s so humble and so beautiful. With Bob, it’s not so obvious because it just swims inside the music. That’s, for me, what’s so incredible about it. If the playing was more predictable, it wouldn’t have been so enchanting in terms of his playing. With the singing, I feel the same way. I feel like he sings in this sort of almost like a plain voice, and he cuts off the words at the end of the phrase. But his range is incredible — his vocal range, but also his emotional range.

For me, it was kind of like Jerry Garcia was like a grandfather when he was young. He’s like this kind of Santa Claus type, or even almost a feminine kind of energy. Nurturing. Bob was the opposite. This sort of punk kid with an almost plain-sounding voice trying to just go for it. I loved that juxtaposition. I don’t think, for me, it could have worked without Bob’s contribution of just that, almost like a kid or a wannabe cowboy wanting to be on this adventure. He went on so many adventures in life, and I just think he totally succeeded.