On Thursday evening, backstage in a dressing room at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, Peter Rowan is plucking his guitar and quietly humming to himself. With less than an hour before showtime, the singer-songwriter will soon celebrate a band he created more than a half-century ago, one whose influence continues to loom large over bluegrass music — Old & In the Way.

“A lot of people who’ve picked up on Old & In the Way have gone deeper into the Stanley Brothers, Lonesome Pine Fiddlers, Bill Monroe,” the 82-year-old tells Rolling Stone. “They follow the trail.”

For a rag-tag group of highly-talented musicians who were only around for the better part of two years in the early 1970s, Old & In the Way remain one of the most important and innovative acts when it comes to the “high, lonesome sound.”

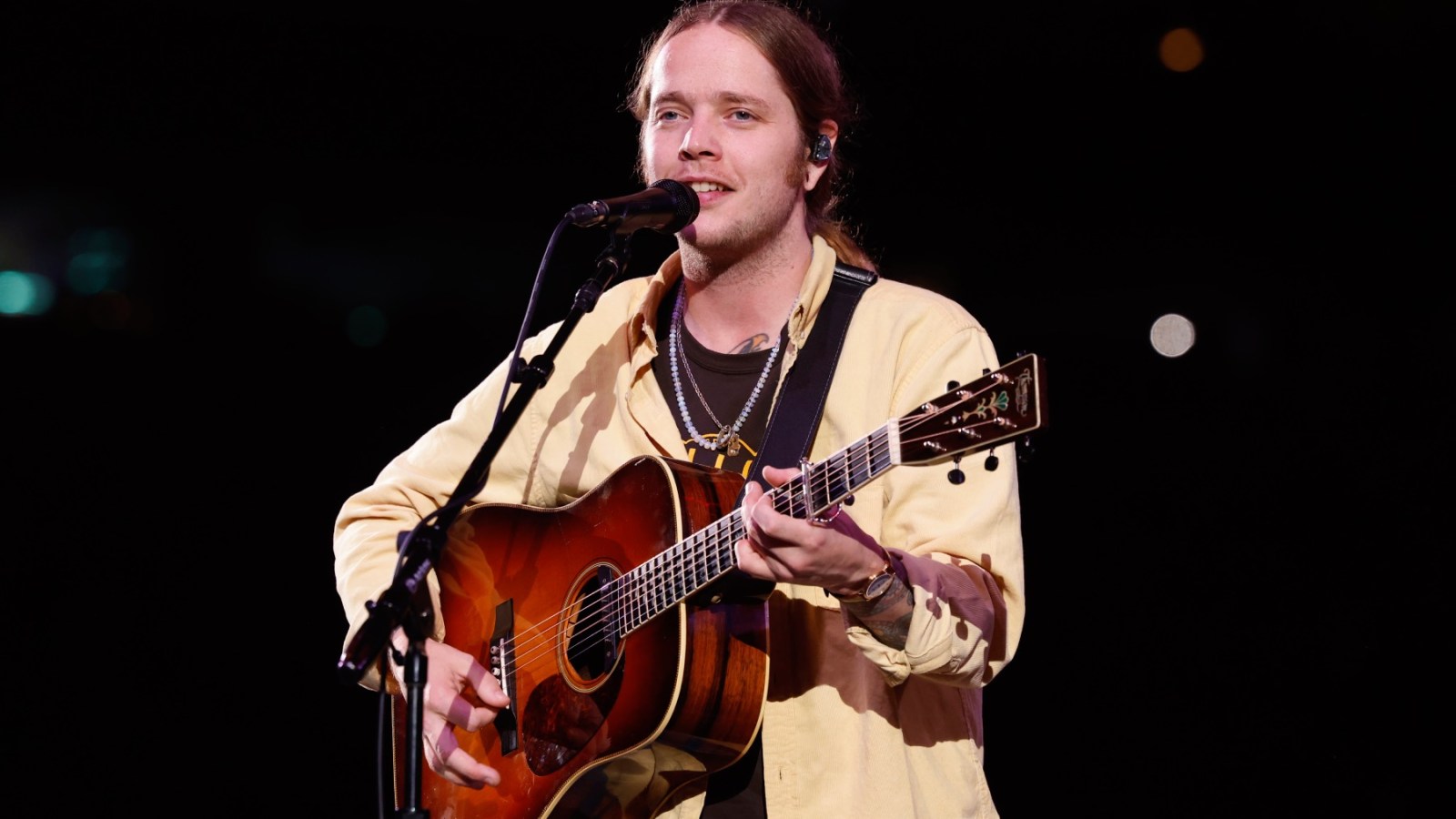

“As bluegrass musicians, we can really hone in on timing and try to think it needs to be perfect,” says guitar wizard Billy Strings. “Old & In the Way? They’re slinky and groovy. They’re not so rigid and firm — it’s loose and fun.”

Strings’ sentiments lie at the heart of what it means to be an acoustic musician — like the members of Old & In the Way — with one foot in musical traditions, the other in the progressive nature of sonic exploration and discovery.

“It brought the hippies and the old-timey bluegrass people together,” multi-instrumentalist Tim O’Brien says of OITW. “They kind of were able to see eye-to-eye and it definitely brought a new audience into the music. It made us youngsters with longer hair more welcome in the community.”

Backed by the Sam Grisman Project, Rowan held court during the Ryman tribute. Alongside Strings and O’Brien, a stunning cast of acoustic stars emerged to partake in the historic evening: Sam Bush, Jerry Douglas, Gillian Welch, David Rawlings, Lindsay Lou, Ronnie & Rob McCoury, and more.

“It’s a whole repertoire of songs to lean on, and with room for your own take on it, where you can have your own voice within it, too,” Lou says. “It gives you the tools and the wheels to ‘get there’ [in your own music]. It perpetuates. It keeps growing and evolving.”

Armed with a handful of Rowan’s songs (“Midnight Moonlight,” “Panama Red,” “Lonesome L.A. Cowboy”), a slew of traditional bluegrass numbers and a Rolling Stones selection (“Wild Horses”), the performance offered many key moments. Rowan soared through “Snow Country Girl” with Welch and Rawlings, a cover of “Hey Joe” spotlighted O’Brien and Bush, and “Going Down the Road Feeling Bad” assembled everyone for the curtain call.

After the concert, bassist Sam Grisman, band leader for the tribute and son of OITW mandolinist David Grisman, took a moment to reflect on the whirlwind night. “It’s an intense wave of history that washes over you when you’re standing on the same floorboards that all those [iconic musicians] stood on,” he says. “You can feel the energy from all these people who played here before.”

Those in attendance on Thursday night, on both sides of the microphone, know that the Ryman is the same stage where Bill Monroe first debuted bluegrass music to the world on the Grand Ole Opry 80 years ago in December 1945. “Bill said, ‘If you can play my music, you can play anything,’” mandolinist Ronnie McCoury says. “And it’s true, if you can play [bluegrass], you can basically get into anything.”

Formed in 1973, OITW serendipitously came about when Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia started having impromptu jam sessions at his Stinson Beach, California, home with Rowan and Grisman. There were no expectations or boundaries, just friends wanting to pick.

“It was something that was organic and fun,” Rowan told Rolling Stone last year. “And that evolved into playing [shows]. ‘Let’s take this outside.’”

With Garcia on banjo, Rowan playing guitar, and Grisman taking up mandolin duties, OITW also featured bassist John Kahn. Richard Greene, John Hartford, and Vassar Clements rotated on fiddle. Rowan, Grisman, and Greene are the only surviving members, with Rowan the lone musician still performing the band’s material.

“It’s fun to have something that is still recognizable after 50 years,” Rowan says. “That’s a gift in the music world.”

And for Garcia, it was an opportunity to return to the bluegrass roots of his youth and offer a respite from the fame brought to him by the Dead. With OITW, the outfit mainly performed sporadic gigs around the San Francisco Bay Area, many being small and intimate affairs.

“I think what makes it so special is that it was like this shooting star,” Rowan says of OITW. “If you were lucky enough to see it, you saw it. If not, you heard about it.”

By 1974, OITW simply disappeared into the ether of time and place, but not before a handful of live recordings were captured and quickly found their way out into the universe. In 1975, the group’s self-titled debut album (a live record) was released and became one of the biggest selling bluegrass records of all-time.

“This is a band that happened in a flash. And the fact those [live recordings] exist, so that it could have the reach and send itself into the cultural bloodstream as strongly as it did,” Rawlings says. “Because if those tapes didn’t exist, there would’ve been three people out there in the audience who heard it and it changed them a little bit. But, instead, it’s changed the world.”

Leave a Comment