From the start, director Bernard MacMahon and writer and producer Allison McGourty knew there would be obstacles involved in making a documentary about Led Zeppelin, especially one done with the band’s cooperation. This is a group that has famously and diligently guarded its legacy, always maintaining a sense of mystique and rebuffing many earlier pitches for a movie like that. “Our sense was that there was absolutely no intention of ever doing a Zeppelin film,” MacMahon says.

Atop that challenge was the matter of what would actually be in the film, since Zeppelin footage is as hard to find as someone in the Seventies who didn’t own a copy of Led Zeppelin IV. As lead singer Robert Plant told the team at a meeting, bringing up their notoriously belligerent manager Peter Grant, “I don’t think this can be told. Peter wouldn’t let anybody film us.” According to McGourty, “Grant would rip the film out of cameras and eject people from their concerts.”

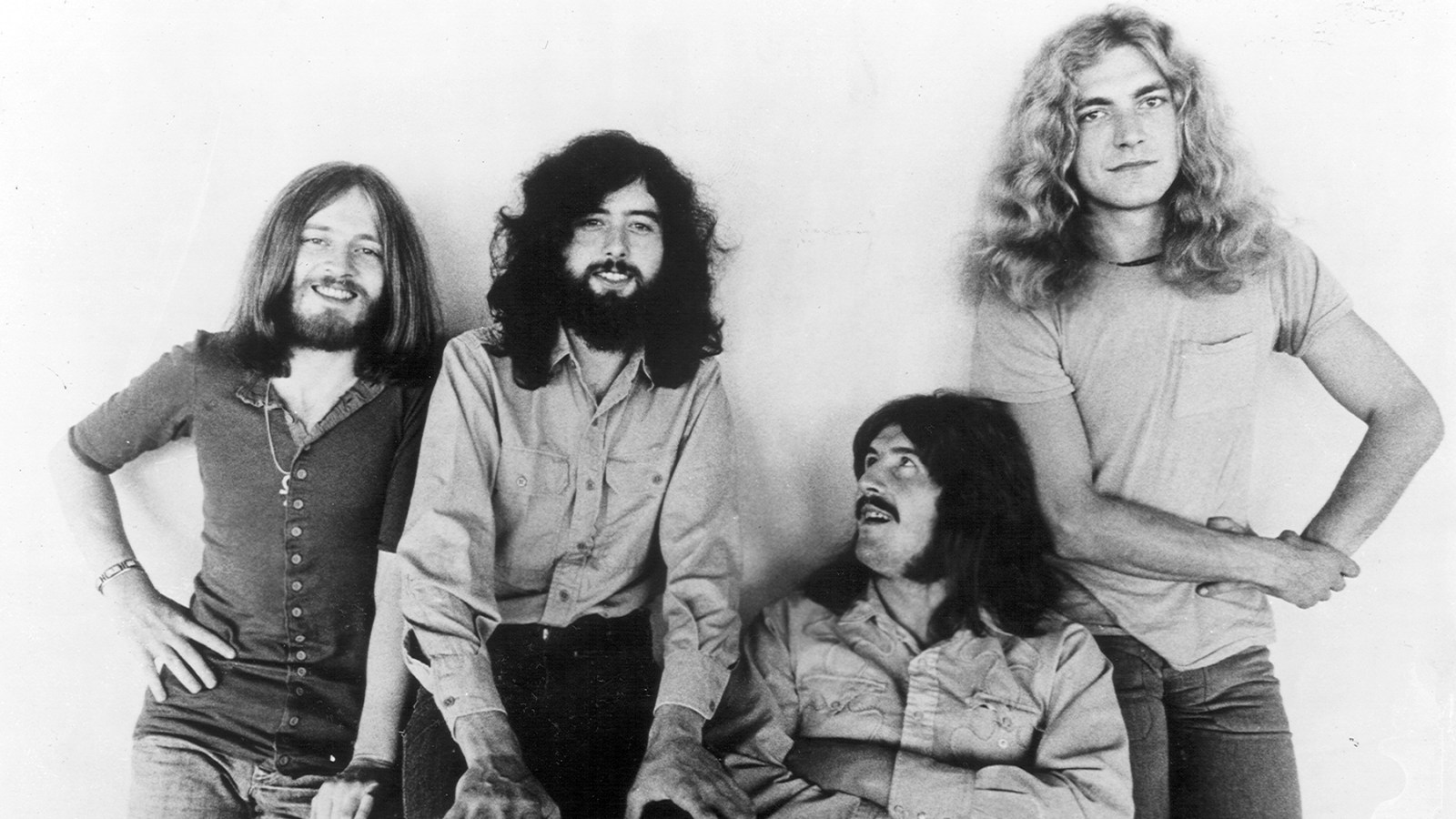

Nevertheless, MacMahon and McGourty carried on, resulting in Becoming Led Zeppelin, a two-hour doc that opened in select IMAX screens last weekend and will have a more widespread release starting Friday. Over its duration, we see Plant, guitarist Jimmy Page, and bassist John Paul Jones, in newly conducted interviews, reminisce about their childhoods and early musical endeavors, from playing in churches to wailing in hippie-rock bands. And thanks to clips that MacMahon and McGourty eventually hunted down, we’re able to hear and see epics like “How Many More Times” and “Dazed and Confused” in all their monolithic, blues-drenched, full-length glory.

What you won’t see, however, is anything of the band’s history past its first two albums: No tales of on-the-road debauchery, no discussions of the making of “Kashmir” or “Stairway to Heaven,” no misty-eyed memories of drummer John Bonham’s death in 1980. Aside from Plant referring obliquely to “drugs and a lot of girls” during their 1969 American tour, the only women in the film are clips of wives and girlfriends. Becoming Led Zeppelin focuses on the band members’ formative years as kids and musicians, culminating with their triumphant show at London’s Royal Albert Hall in 1970. “If you were doing a movie about the space race, it would be the journey through the Fifties and it would culminate with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landing on the moon and then returning home,” MacMahon says. “That’s the end of the story.”

As dazed or confused as Zep fans may be by that framework, MacMahon says he and McGourty had always planned on Becoming Led Zeppelin to focus on the “becoming” part. They envisioned a 120-minute work that could be shown in theaters for the maximum immersive sonic experience. MacMahon also thought back to a Zep paperback he owned as a kid that only told the group’s tale up through the early Seventies. For him, the saga after the completion of 1969’s Led Zeppelin II isn’t nearly as compelling as what came before.

“That story didn’t interest me,” he says. ”Up to 1970 is the point where everything that happens is unique to them: the combination of these four individuals and the specific things they do and the choices they make and how they become hugely successful. Once that is achieved, the events that follow are often incredibly similar to countless other things that have been successful.”

“Album, tour, album, tour, album tour,” adds McGourty.

MacMahon, on a dual Zoom with his collaborator, nods in agreement. “This person falls out with this person. Someone becomes a drug addict. Blah, blah, blah. You’ve just heard it over and over again. But who these people are has never come out. No one knows who they are, personally.”

Such a limited time frame must have also appealed to the band, sparing them from revisiting tragedies like the death of Plant’s five-year-old son Karac or having to address any groupie tales. But to press their case, MacMahon and McCourty spent half a year researching the amount of archival footage they could potentially use. Then they compiled those images to create a storyboard — a visual script — in a black leather-bound portfolio that they brought to each band member in meetings.

“They weren’t open to it when we met with them,” MacMahon admits. “But as we were walking through the storyboard, it’s as if we were walking through their childhoods.” During a seven-hour sit-down with Page, MacMahon felt a moment of revelation when they arrived at photos of the studio where the newly formed band first jammed on “Train Kept a-Rollin’” for nearly an hour. “I remember Jimmy had this sense of joy appearing on his face like he was back there again, and remembering what he thought of them back then,” MacMahon says. “Those feelings were coming back. I could see him going, ‘Oh, you know, this could work.’”

MacMahon believes that the band also responded to American Epic, his 2017 series (co-produced by McGourty) about early 20th-century American roots music. “I think it touched them to be considered as following on from Charley Patton and that film’s approach to getting inside the music, its influence and what made it,” MacMahon says. “We came presenting this story that was similar to the American Epic story, except it was about them.”

Which isn’t to say the filmmakers weren’t tested. During one early conversation, MacMahon says Page asked them to name the band Plant was in when Page first heard him sing. MacMahon correctly answered “Obs-Tweedle.” “And Jimmy said, ‘Very good. Carry on.’”

With the band’s blessing, the director and writer interviewed more than 100 Zep associates, from pals from their youth to engineer Glyn Johns. In the end, they would up using those conversations primarily as fact-checking tools and not incorporating them into the film. “People waited this long to hear the group tell their story,” McGourty says. “They’ve never done it before. So let them tell it.” To jog the band members’ memories during those interviews, the two would show them vintage photographs of buildings from their youth or blast a piece of music especially loud.

But as they were warned, film or TV footage of Zep during that period was hardly plentiful. The filmmakers eventually came upon three unheard interviews with the press-shy Bonham from the early Seventies and were given access to his father’s home movies of young John by way of Bonham’s sister. When they heard about the existence of illicitly shot footage of Led Zeppelin’s 1969 show in Bath, McGourty flew from L.A. to the U.K., to what she calls “this mysterious little medieval village where they filmed the windmill in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.” There, the owner of the footage agreed to let them use it, but with preconditions. “I had to send a car for him so he could accompany it all the way to our London facilitator to transfer it,” she says. “He didn’t want to let it out of his possession.”

MacMahon and McGourty say they had editorial control over the contents of the film, and Page attended a screening of a rough cut at the Venice Film Festival in 2021. Later, Plant attended another screening in London and turned to McGourty and said, “That was my life.” Since Plant’s family apparently didn’t know that his parents had kicked him out of the house when he chose to pursue music, their reaction, McGourty says, “was very moving.”

So, will there be a sequel that ventures into Led Zeppelin’s later years? The filmmakers are cagey. “I haven’t even given it a second thought,” says MacMahon. “This is the film we wanted to make. It was like climbing Everest. All I know is a sequel would be an enormous amount of work. I don’t contemplate that lightly.”

Although it’s not a biopic, Becoming Led Zeppelin could also serve to introduce a generation born this century to more rock gods of old, the way Bohemian Rhapsody, Elvis, and now A Complete Unknown already have. MacMahon says that wasn’t the plan, yet he can envision such a scenario.

“The moment the kids go into that cinema and hear that music coming out the speakers, some of them are definitely going to be thinking, ‘I wonder if I could do that,’” he says. “It’s kind of a clarion call. You can do this. You just need three other buddies and one other bloke keeping everyone away. You don’t need 100 samples and fucking 10,000 lawyers having to give your songwriting credits to 15 engineers.

“And,” he adds, “who wouldn’t want to wear those clothes? That shit looks cool.”

Leave a Comment