TV on the Radio, the celebrated group whose experimental amalgam of rock, post-punk, electronic, and soul made it sui generis in the 2000s New York scene, knew it was time for a break. It was 2019, and after nearly 20 years and five albums together, the nonstop demands of recording and touring had taken its creative and physical toll.

For co-founder Tunde Adebimpe — let’s stick with “co-founder” and not “frontman” for reasons that will be explained later — it was a time to both recalibrate a bit and dig through demos that, for one reason or another, didn’t make it to a TVOTR album.

But in June of that year, someone broke into Adebimpe’s garage and stole his laptop, 15 years of hard drives and all of his backups. “And tons, tons, tons of demos,” he says. “It’s stuff that’s meaningless to anyone else.” (His studio space in downtown Los Angeles was also the victim of a presumably unrelated break-in. “It felt a little cursed for a while,” Adebimpe says.)

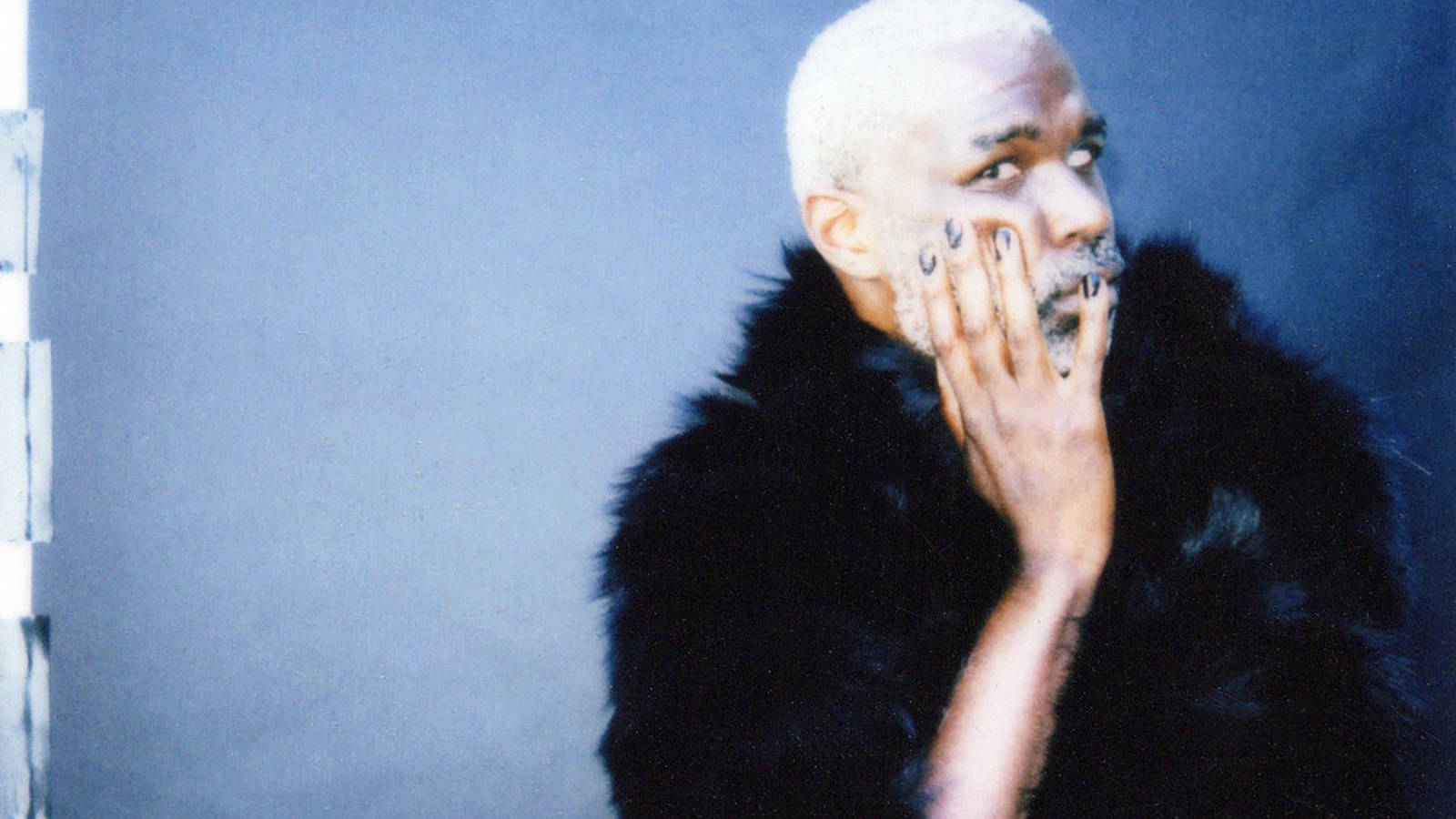

For more than 25 years, Adebimpe has quietly been one of culture’s most creative multihyphenates. He was one of the first animators on MTV’s turn-of-the-century claymation gorefest Celebrity Deathmatch before turning his attention to music — he remains the group’s co-vocalist and principal songwriter, has made numerous guest appearances and recorded multiple side projects — and film. (Adebimpe has mingled indie performances like an acclaimed role in 2008’s Rachel Getting Married with the bigger popcorn fare of Spider-Man: Homecoming, Twisters, and last year’s Star Wars: Skeleton Crew.)

Along the way, he’s been a director, voice actor, art director, cartoonist — you get the idea. But having just turned 50, Adebimpe can now add a new appellation: solo artist.

Thee Black Boltz, co-produced by Wilder Zoby and out Friday via Sub Pop, is a devastatingly gorgeous listen colored by unimaginable loss yet imbued with optimism. In 2021, as Adebimpe was still mapping out the album, his 41-year-old sister Jumoke died suddenly of a heart attack. “The whole album is dedicated to her,” Adebimpe says. “She’s probably the closest person in the world to me.”

Adebimpe’s voice has always had a comforting warmth belying the “basement hardcore shows” that soundtracked his teens. But tracks like “ILY,” a sparse elegy to Jumoke, and the skittering, Kid A-channeling “Drop” feel like sonic gut punches. The former, an album highlight, could somehow soundtrack both a wedding and a breakup; a paean to immortal love or the audio to that which was once cherished and now gone.

Adebimpe, however, tries to remain upbeat on Boltz, attempting to turn life upheaval both globally and personally into pockets of exuberance. “Pinstack” sounds like a slightly fractured take on a Sixties pop song, while album closers “Somebody New” and “Streetlight Nuevo” veer more dance-pop and otherworldly keyboards, respectively.

Speaking to Rolling Stone in his Los Angeles garage in March, Adebimpe takes out a notebook filled with various artwork and rough musical references he looked toward for Boltz, which included everyone from Suicide, the Stooges, and Nation of Ulysses to Nick Drake, Bjork, and Tom Waits.

The garage is filled with books, art supplies, a Mellotron and a small mixing board all befitting his diverse interests. A board with photos of Toni Morrison, one of Adebimpe’s heroes, and Gerard Smith, the former TV on the Radio member who died in 2011, are never far from him. The band reconvened, sans founding member Dave Sitek, for a series of celebrated live shows last year. (They’ll tour Europe and North America this summer.) But for now, Adebimpe is firmly in “solo mind.”

Numerous labels rejected this album. Why do you think that was?

I’m so incredibly psyched to be on Sub Pop, a label that was responsible for me even thinking I could make music. It was early days in the pandemic and people were confused about touring and didn’t want to take on any new acts. I also think it was that I’m not a young, sexy superstar who’s…

Slow down, Tunde.

Oh, it’s all right. It’s not negative. One of the things about hitting 50, you just know yourself. Maybe I’m an old, sexy pop star.

Did that affect your ego?

One hundred percent for about two days. The first day, I was just like, “Oh, right, it’s not 2008 and this isn’t the band.” But it was good [because] I don’t know what people are thinking and I shouldn’t let that affect what I’m doing. And coming up in [the] punk-rock DIY scene doing basement hardcore shows, it’s like, “If you tell me that I can’t do something, the thousand ships that I’m going to launch with the words ‘fuck you’ are going to be long and strong.” It was good to go back to zero and be like, “The great thing is it feels like nobody cares. So, we have to care and just have fun.”

How conscious were you of differentiating Boltz from TV on the Radio?

With TV on the Radio songs, especially by [2014’s] Seeds, [the band’s last album], I’d gotten used to writing demos and thinking like, “Okay, I’ve got this part and I don’t really have to worry about these other parts because I know [member] Kyp [Malone] will have an idea that goes there and I’m writing this with that negative space in it that I know that he or [members] Jaleel [Bunton] or Dave [Sitek] can fill in a great way.”

I have a face-recognition blindness [with TVOTR] where I know that we made that, but I couldn’t tell you how we did it. We get into this trance where we feel more about it than think. I guess I know what a TV on the Radio song sounds like, but whatever I’m writing is a combination of all the influences I’ve had musically since 16 or 17 when that stuff starts to drill itself into your head and all the detritus of that floating into whatever you’re doing. The only way for me to make something that’s definitely not a TV on the Radio record was if I made a country-rap record.

Did last year’s shows almost feel like a victory lap of sorts? The clichéd “elder statesmen of rock” return.

Victory lap sounds a little braggy, but it’s just like you get to reconnect with people who’ve been with you from the start, and you get to see so many new fans. And that’s one of the coolest things about going back out is realizing there are people who — it sounds so weird to say — but just were not born when we started.

How were the crowds different than in the 2000s?

One of the coolest things is there were way more Black and queer kids and people of color than when we were starting and [seeing] it be a regular thing instead of this weird fucking anomaly. You’re talking to these young punks, and it was just like, “We would’ve been best friends in high school, but you weren’t around. And I’m so happy that anything I’ve done has led you in this direction.”

I want to detour into nostalgia a little because TV on the Radio almost feel like a totem of a particular era, time and place for fans of a certain age. What does the word “nostalgia” mean to you?

I think it’s a gratitude for all the things that happened to bring me and us and anyone who’s listening to this point. There’s so many other musicians … Bartees Strange told me, “When I saw the ‘Wolf Like Me’ performance on Letterman, it was a big part of me thinking, ‘I want to do that.’”

You once said “I don’t know who that person is” when looking at photos of yourself from years ago.

You have a vague idea, but you can be a little jealous of this person who had no idea how wrong things could go. So you went full on as far as you could and didn’t have any fear about that because they didn’t know what to be scared of. It’s funny to hear about things like electroclash being this huge movement, and I’m kind of like, “electroclash was two bars over the course of a month and a half.” But nostalgia is not something I’m interested in right now. The pandemic was one of the first times in my life that I was like, “Wow, I’m looking backwards more than forward” and that’s a really unsettling feeling.

There’s a poignant line on the new album from “Magnetic” about being in “the age of tenderness and rage.”

Yeah, there’s this British photographer named Misan Harriman, who takes beautiful, moving pictures at protests. He took a photo of someone at a Black Lives Matter protest in 2020 with a sign that said “This is the age of rage and tenderness.” It encapsulated to me the feeling of the times. Sometimes, it feels like there’s waves of evil coming towards you, and you have to combat those by being a decent person and standing up for people who cannot stand up for themselves. But to do that, you have to be open to those feelings. You can’t shut yourself off if you don’t want to get steamrolled by racists and sexists and fascists. There’s a lot to rage against, and it’s because you have some kind of love in your heart that you want to fight.

The day after Trump was elected last November, you posted a quote from Toni Morrison about, “This is precisely the time when artists go to work.” What does “work” look like for you?

That’s also the question: What role does art have in all of this? I don’t know. It might be really naive, but for me, it’s making music or art that connects people and lets them know that there’s a place for them in this and encourages people. It could even just be dance tracks, if you need to flail around in your room in the morning so you can go out and recognize everyone as human.

I’m not someone who is striving for a bunch of attention. But if someone’s going to be pointed in my direction because of something I’m doing that they like, I feel obligated to share information with them. If I feel like something’s fucked up, I’m going to let someone know this is fucked up and it doesn’t have to be this way. The problem is getting it to the people who really need to have a point of view expressed to them in a way that can resonate with them. I have not figured out how exactly that can happen.

“ILY” finds you talking to your sister. How difficult was it to write?

The circumstances around it were hard, but writing it wasn’t difficult. I have such an admiration for simple and effective songs because you can hear something that sounded like it’s there forever. It’s pretty much just a letter to her saying, all of these messy feelings boil down to the fact that our love remains. You think about them even more than you did while they were here.

[After her death], I was like, “I don’t think I’m going to finish this record. I actually don’t want to do anything right now.” But that’s the great thing about the safety net of art: I’ve got a built-in thing where it’s just like, “Well, you’re thinking about this. You’re just going to drive yourself fucking crazy until you write it … and put it in a place where you can look at it like a scale model of these feelings.”

How do you feel she manifested herself on the album?

We were four years apart, but we were twins, essentially.… I feel so lucky to have been this particular person’s brother and so lucky that she was my sister because we got to kick through this weird-ass world together and had such a shared affection for things and were each other’s biggest cheerleaders. Whenever one of us felt like, “I’m not really sure about this,” the other one was just like, “What the fuck are you talking about? You’re the shit. I’ve been around for 20 years and there’s nothing about you that doesn’t let me know that you can do whatever the fuck you want. And I’ll always be here to tell you that.”

When I flamed out after she passed away, one of the things that kicked in was she would’ve been like, “No, you got to go harder now. You have to make good on the promise that you made to yourself forever ago that this is your path and that you’re not going to shy away from feeling these things. And that maybe if you put all of this shit in a place, it will help someone out the way that it’s helped you out.” I’m going to give you a few words of advice or solace or let you know how I worked my way through this so you know that you can do it.

You’ve talked a lot in the past about having stage fright. Does being a solo artist amplify that fear?

I don’t know if it’s easier, but it’s just normal now. If you’re in cold weather, you’re just really sharp about shit. I’m very aware of everything. I think it’s mostly having a slight anxiety about wanting to do the best that you can do and leave enough space where you can still play with what you’re doing. It’s more of a giddiness where you’re just like, “Oh shit, I don’t know what’s going to happen.” And that’s really exciting. I would love these shows to be really raucous.

I was reading an article a few years ago where Kim Gordon was talking about how music and shows don’t feel dangerous anymore and I knew exactly what she was talking about. Where there’s some moments where you’re just like, “Oh shit, should I be this close to the stage?”

You occupy an interesting perch when it comes to fame and celebrity. You get stopped in certain places but from the outside, you always felt like a reluctant rock star. TV on the Radio always felt like a repudiation of the genre’s worst impulses.

I just don’t … I don’t know. For me, in whatever scenes I was coming up in, a rock star was a bad thing to me. It was a negative. Where it was sort of like, I don’t have a Jimmy Page or Bono or any of the “masters,” I guess. That’s not my floor of the building. I don’t even like the term frontman.

Why not?

It just sounds so gross.

You were an usher at New York’s Film Forum in your early twenties. What’s the best story from those days?

I don’t know if I should say. It was a sleepy enough theater at points where when we went to take the garbage out, a co-worker and I would just get stoned and come back in and call out the movies in a really childish way. There’s this movie called La Maman et la Putain, which [translates to] The Mother and the Whore. It’s a great movie, but these two fucking 20-year-olds yelling, like, “6:30 showing for The Mother and the Whore!” Very un-Film Forum. The manager was just being like, “Guys, could you just chill out?” And we’re just like, “What do you mean chill out? We’re just ushing. We’re ushers.”

What’s the status of a new TV on the Radio album?

We’re not doing anything right now, but the nice thing about these shows is that it’s like, “I don’t know what’s going to happen and I’m fine with that because as a band, I know that we’ve built this motorcycle and we know how to ride it. We can do wheelies and donuts, all of that.” Just coming back together and being like, “This is something that we know how to do and can have fun with that.” We’ll probably figure it out over the course of this tour. It’s just fun again.

Can you start to envision what it looks like or are you firmly in solo mind?

I’m in solo mind, but everyone’s always writing and I’ve got a bunch of stuff that just didn’t make it onto this record that I could see if the band wanted to do it. Whenever we do things separately and come back together, it’s like everyone went to either their little university or vision quest and brings back what they learned from there.