S

ome connections are cosmically fated. Justine Dorsey and Graham Epstein first met on the dating app Hinge, bonded by an affinity for the type of breezy, infectious pop music from the early aughts. Both happened to be born on the same day in 1995, adding to the mystical alignment of it all. Though things never took off romantically between them, the relationship would blossom into a musical partnership. “We became friends because we’d see each other out at parties and stuff,” Dorsey recalls. “And then, one day he messaged me, I don’t know why, but he was like, ‘We should start a Y2K pop rock band.’ And I was like, ‘Yes, we should. That sounds perfect.’”

Their band After — which gets its name from an obscure Japanese PlayStation game — feels like a memory you can’t quite place. Dorsey’s soaring vocals blend seamlessly with Epstein’s shimmering production, striking a balance between familiar Y2K nostalgia and something wholly original. “I was thinking how no one’s doing mainstream radio hits that are inspired by that era,” Epstein says. “Kind of like, a very specific sound they had back then. And she has an amazing voice, so I was like, ‘It’s perfect.’”

We’re seated on a bench at New York’s Tompkins Square Park in May, ahead of the band’s first concert in the city, which summoned a sold-out crowd off the strength of their debut self-titled EP released in April. Standout songs like “300 Dreams” and “Obvious” have the sparkly 2000s-style electronics of PinkPahteress or Oklou, but with a sense of songcraft that feels, well, classic. “We wrote a bunch of songs pretty fast on acoustic guitar. And then kind of fleshed them out later,” Epstein explains of their early recordings. “We have a very specific language and palette that we stick to. It was a good marriage between my sensibilities and her sensibilities, creating pop music.”

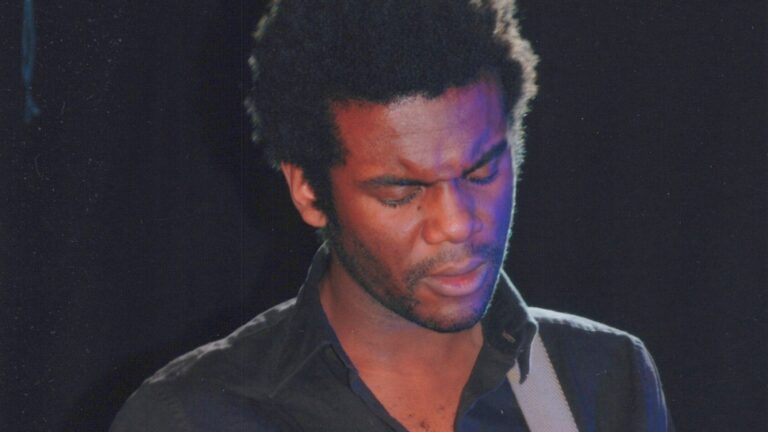

After in Los Angeles, May 2025

Adali Schell for Rolling Stone

The pair started the band around 2023 after ending their respective musical projects. Epstein’s background was originally in bands making shoegaze and post rock while Dorsey’s earlier work was more inspired by Blondie and the Talking Heads than anything from the 2000s.

More than jumping on a trending sound, After has found a way to tap into a sensibility that cuts to the core of why listeners feel nostalgic for the early 2000s in the first place. “We’re not trying to be ironic at all,” Dorsey adds. “Even with lyrics, like for ‘300 Dreams.’ I was low-key trying to write a positive song, like a happy song, which is very Coldplay coded.”

“We’re obsessed with melody, like things being really satisfying to your brain,” Dorsey adds. “So much of indie music or alternative is really vibe based and not satisfying and structured or melodic. We always say we wanted to make you miss a memory you never had. That’s baked into the songs.”

Fittingly, After’s listeners so far have keyed into the way the music makes them feel. “All of the Tik Tok comments are like, ‘this reminds me of driving to Kohl’s with my mom,’” Epstein says. “It’s just kind of cozy like pop hits that were already on the radio.”

All of this could make one feel cynical, if not for the sheer strength of the music. While Y2k nostalgia is seemingly everywhere, nothing feels or sounds quite like After, possibly a result of the band being right at the age where their feelings about the era are coming from both appreciation and experience. “Someone who’s maybe a little older than us could be really jaded about it. We’re still excited by it instead of being like, ‘Oh I just heard all those songs before,’” Dorsey says. “And then, it’s cool to see when really young people like the songs. And they’re nostalgic for something they didn’t experience.”

The same goes for the pitch-perfect aesthetic sensibility they’ve been able to cultivate. “It’s in the visuals, too. It’s trying to introduce people to this aesthetic, probably seen when we were kids, from tech commercials and JCPenney, just random stuff.”

Perhaps there’s something to the fact that those on the cusp of Millennials and Gen Z have a kind of comforting relationship with retail experiences from their youth. Dorsey points to an Instagram page she’s been following that digs up all of the old playlists that used to play at Gap stores. “It’ll literally be like Gap Body Holiday 2005 and then all those songs that would play at the stores. And a lot of the music is actually stuff that we reference all the time,” she says.

After in Los Angeles, May 2025

Adali Schell for Rolling Stone

“All the stuff that we play has been done, I feel like. It’s like into 2000s, like the break beat pop stuff. Even bands that were kind of small. I think it’s all been done already, it’s kind of crazy,” Epstein adds. “We try to bring a new touch to it, but it’s just crazy how everything was invented in the Nineties and 2000s.”

Except, After have very much invented something, albeit something built from past materials. Both say they have a sense of Zen about the band’s future. Part of the reason they were in New York was to take meetings with labels, none of which seemed to be stressing them out. “Since we started the band, I’ve been so calm and confident about everything. And I’ve never felt that way about anything,” Dorsey says.

“We’re not usually delusional like that either. I don’t have confidence,” Epstein says

Dorsey concurs. “Same. I feel like I’m expecting the worst.”

Epstein puts it best: “There’s something about this band that just clicks with us.”