The floods that brought destruction and heartbreak to the Texas Hill Country, and Kerr County in particular, since July 4 have rippled through the independent Texas music community. According to authorities, at least 111 people have died, with more than 170 still missing. Hardest hit was Camp Mystic for Girls, a Christian summer camp west of Kerrville along the banks of the Guadalupe River, which rose more than 25 feet in under an hour early Friday morning. Dick Eastland, who ran the camp along with his wife, Tweety, died while trying to rescue campers in the floods.

An hour outside of Austin, Kerrville and the Hill Country are inseparable from Texas music. The annual Kerrville Folk Festival is upstaged only by those in Newport and Telluride in prestige. The region is home to many of the biggest artists in Texas music, and the same Guadalupe River is celebrated in dozens of Texas songs as a place to drink beer, float, and escape into nature.

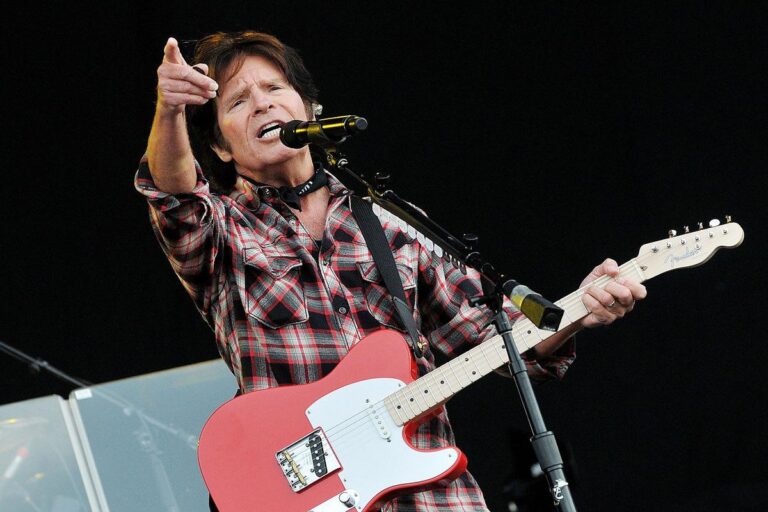

The floods’ impacts on Texas music have been far-reaching. Pat Green, whose rise in the late 1990s ushered in the modern era of Texas music and still impacts the scene today, saw his family devastated. Green’s brother, John Burgess, along with Burgess’s wife and two of their three children, died in the floods. Others in the scene were spared, but at a heavy personal toll. Hill Country artist Julia Hatfield and her husband narrowly escaped while camping after floodwaters inundated their RV; they witnessed others swept away. Venues of all sizes along the Guadalupe and its tributaries were flooded, with some, such as Lone Star Floathouse in New Braunfels, sustaining heavy damage.

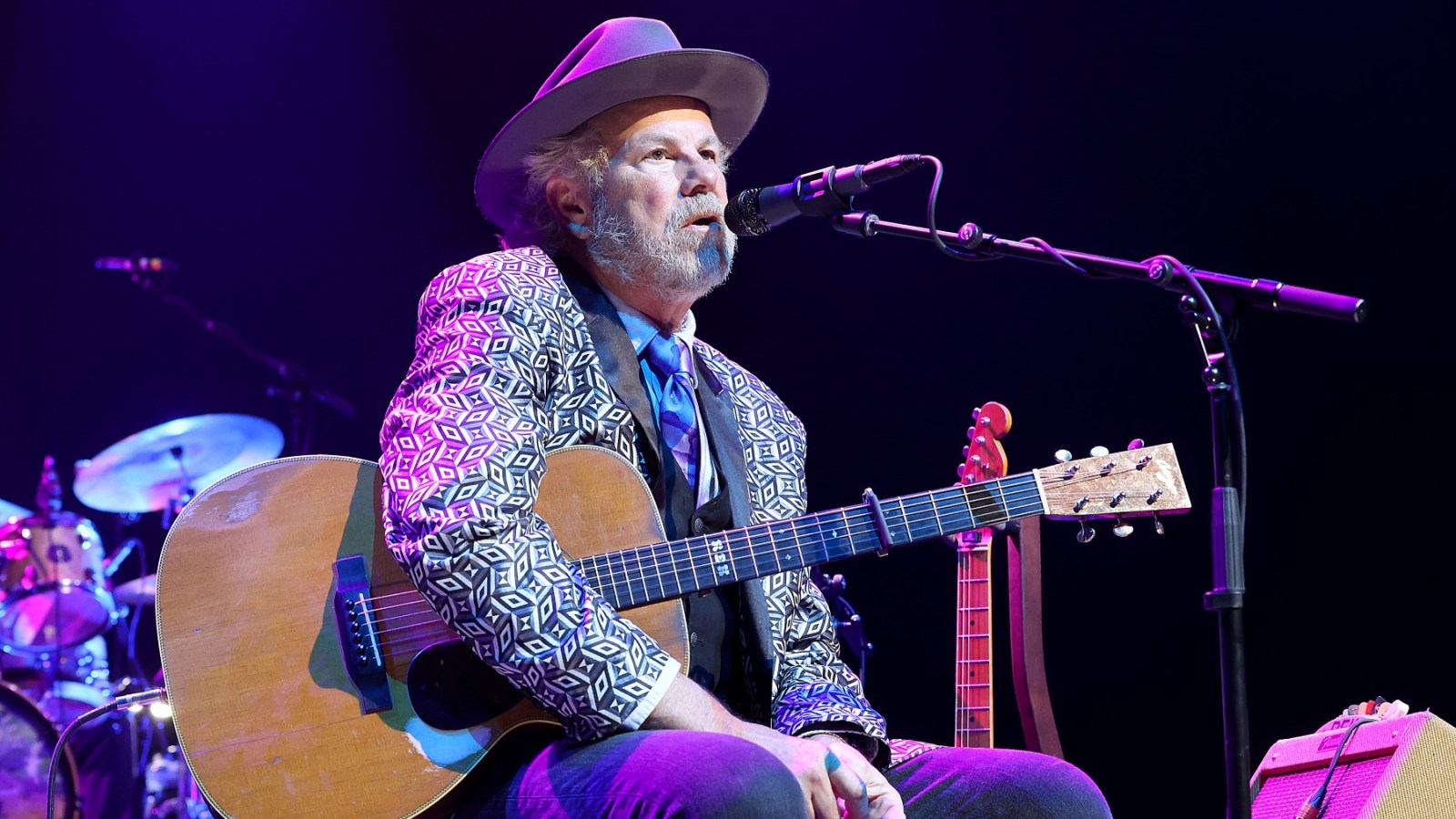

Robert Earl Keen has been affected from multiple angles. Keen, one of the most influential artists in Texas history, has a ranch outside Kerrville. It’s where he thought he’d spend his retirement in 2022, and it’s where he first returned to the stage late that year for an acoustic show when retirement didn’t stick. Starting in the late 2000s, Keen’s daughters, Clara and Chloe, attended Camp Mystic in the summers. This July 4, Keen was scheduled to play Kerrville’s Fourth on the River, along with William Beckmann and Jamie Lin Wilson. It’s a festival Keen has been a part of for most of the past 15 years. The floodwaters covered the festival grounds and destroyed the stage and production equipment. The Arcadia Live Theater, which acts as a festival host, became a makeshift family reunification center and shelter after the floods.

Keen has been touring since the floods, and donating all of his merchandise sales to flood relief efforts. He spoke with Rolling Stone on Tuesday before a show in Fort Collins, Colorado. His oldest daughter, Clara, who works at the Americana Music Association, exchanged emails with Rolling Stone on Monday. They shared memories of Camp Mystic, the ties that bind music and Kerrville, and offered advice for fans and artists seeking ways to help.

What did Camp Mystic mean to your family, as a community and as a place?

Robert Earl Keen: It was very Christian-based, but they embraced everybody. Dick and Tweety Eastland were always, for lack of a better word, cheerleaders for the whole bunch. On the days when they were all checking in, there would be these huge masses of maybe 30 or 40 girls there to welcome the new ones, and clap and embrace them. It was heartfelt and real. They were very committed to what they do. I never thought about it being any kind of moneymaking operation to them. It was just them doing what they did, which was giving as much as they could to the kids.

I just found out that my youngest daughter, Chloe … a cabin that washed away was the cabin that she stayed in when she was first there, and she has a definite visceral connection to this tragedy. My older daughter went there for eight years, and she just loved it. And, for me, the connection was that you didn’t get to have phone calls with your kids, so you just wrote letters. That was a different kind of a connection. Anybody that had kids going to Mystic did the same. There was letter writing and sharing pictures. Those ties are as strong as tungsten, you know?

Clara Keen: Mystic had a very strict no-tech policy. If we wanted to communicate with the outside world, you had to write letters, and we all did that. I still get a lot of joy out of writing and receiving letters, because the act of opening an envelope still transports me back to hot afternoons in June, sitting on my bunk bed during rest hours just poring over letters from my parents and friends in the world beyond Mystic. My dad would write letters called “The Farm Report” where he would write about the ranch and how all the animals were doing. My friends at camp loved those and would always ask to read them.

It was a fun camp and it was a place to bond with other girls of all ages, which I think my parents always kind of worried about. I was definitely a weird kid and too much of a know-it-all to make friends easily in “real life,” but at camp, that didn’t matter. Making and keeping friends was not only easy but a sincere joy.

Mystic allowed me to grow into myself, on my terms but with the help of good-natured guidance that was structurally integrated into the camp. That was an extension of how my parents were already raising my sister and me. Looking back, I realize Mystic shaped innumerable aspects of my character, to the point where Berton Brayley’s “Prayer of a Sportsman” is the only poem I know by heart, as it was recited after every team game at camp.

What was the relationship between the camp and the river?

Clara: The river was an intertwined part of camp life. As a camper, you quickly learned it was in your best interest to have some sort of water activity on your schedule to beat the heat. But you didn’t want it to be too early because the water would be too cold. The river was this constant, not only during the term but over the years. As I grew older, the river remained the same. It shaped everything from swim lessons to camp-wide activities like canoe races. It’s reshaped everything now.

What are the ties that bind music and Kerrville?

Keen: I believe you can trace it back to before then, but in 1972, they held the first Kerrville Folk Festival. It was in a community building, and there’s still pictures of it, and you can actually see on the very front row was LBJ listening to somebody singing. One of the things that they do better than anybody else, as far as a festival, is that they really don’t spend a lot of money. They go and get a lot of new artists. You can hear artists you’ve maybe never heard of from all over the world. They’ve embraced people from other countries. They bring them in, and you can see and hear this great music. Around that, the arts scene — visual arts, painting, community theater — is a lot stronger than a lot of places, especially in a town that size. I would say it’s part and parcel of the whole culture of Kerrville. Were it not for the festival, maybe some of those things wouldn’t have come together.

My connection started in 1981 when I won the “new folk songwriter” award at the Kerrville Folk Festival. I lived in Austin at the time, but I knew how to get to Kerrville. So, I would drive people like John Gorka and Peter Rowan out there. I got into the funniest conversation ever between Junior Brown and Peter Rowan, which are the opposite ends of the spectrum — just talking about smoking too much weed and going on stage. It was hilarious.

Clara: Kerrville has a long history as a supportive music town. It may not be Newport, but the Kerrville Folk Festival has been a longstanding musical pit stop for anyone in the folk and Americana scenes, and is something which is braided into the community. Its growth and embrace of those genres, year after year, is nothing but a testament to not only the resilience of the music but the strength of the people that love and work to support it. We also see this in organizations like the Hill Country Youth Orchestra — which teaches kids K-12 to play classical music. As someone who grew up in Kerrville, one of the things that has been so exciting in recent years is the development of spaces like the Arcadia Live Theatre, which specializes in contemporary performance, and just community restaurants like Pint & Plow, which provide local musicians with house-concert level support and spaces to play.

It’s not a place like Austin or Houston, which host a number of venues, but it’s still a substantial ecosystem that thrives on a loving and supportive community. And I’d trade a stadium show for that every time.

How have you approached flood relief efforts from the road this week?

Keen: That’s my strongest connection to all this. We had something like 12 years in Kerrville doing Robert Earl Keen’s Fourth on the River. Then, I quote-unquote retired, and stepped away from it. They had a really rocky year last year, and they asked me to come back, so I did. And now, with it being washed out, I kind of feel like I was somewhat of a spearhead or a flashpoint, as far as the other artists who are now part of the whole tragedy.

So, immediately, we decided to give a hundred percent of our merch to relief. We haven’t confirmed it yet, but we’re going to be putting on a show. We’re making sure it’s going to be a real solid musical event, and we’re going to be announcing it all in the next day or two. And, my wife is at home, and she has been running around, ferrying people and first responders to places. We had a little place that we were trying to rent, and she just handed that over to some first responders. She’s been picking up trash for them and doing her thing. It’s an entire family effort. You can’t take away what happened. You can only go forward, and do as much as you can, for as long as you can.

Aside from a benefit show, what can people do to help right now?

Keen: If people want to send money, or if they’re putting together their own concert or event, send it to the Community Foundation of the Texas Hill Country. We vetted all these ideas, and thought about the Red Cross, but this is the closest one and strongest one that really is all about the Hill Country and Kerrville.

Clara: I would really ask those who are willing to listen to show kindness and grace. Texas is not a monolith, and there are people here who have loved and lost on a level which is dark and incomprehensible. People, these people, deserve supportive love more than anything at this time. As the Eastlands at Camp Mystic taught me as well as so many other women: “A bell is not a bell until you ring it. A song is not a song until you sing it. The love in your heart wasn’t put there to stay, love isn’t love until you give it away”