Rock ‘n’ roll history includes a long and colorful tradition of contractual obligation albums, one that’s brought us a handful of unintentional classics as well as a number of records that are so bad — or so bizarre — that they simply have to be experienced. Few if any artists, however, have elevated malicious compliance to an art form quite as savagely as Van Morrison.

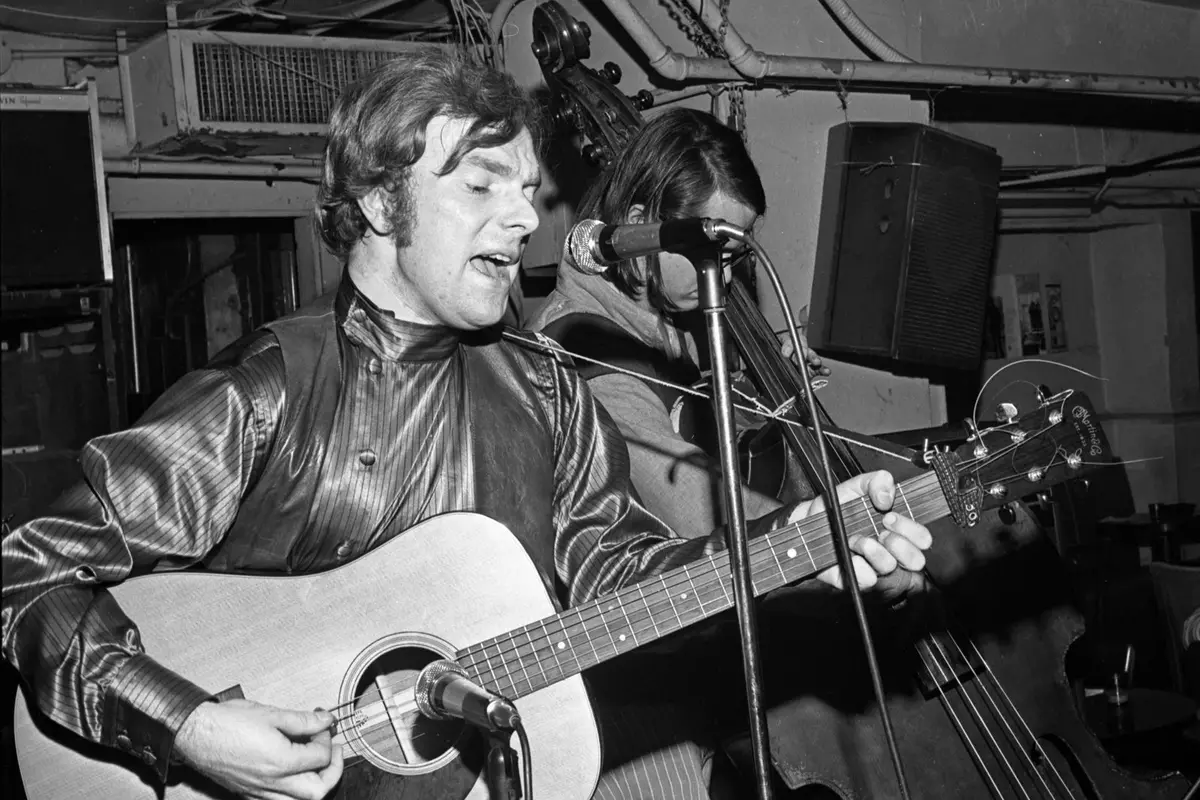

As Morrison fans have long been aware, his frequently contemplative music exists in tandem with a classically pugnacious spirit; whether he’s grumbling his way through interviews or forcing audiences to hold on for dear life through legendarily mercurial concerts, he’s made a point of being forcefully his own man throughout his career. Since aging into elder statesman status, that attitude has made Morrison seem like a classic curmudgeon, but he’s been this way since he was a young man — and it could be easily argued that he came by it honestly, particularly at the dawn of his solo career.

Like a lot of young artists, Morrison didn’t necessarily know what he was getting himself into when he signed his first solo deal. After leaving Them in 1966, he was lured to New York by producer Bert Berns, who’d been familiar with him since Them covered Berns’ “Here Comes the Night” the previous year. Once there, Morrison was offered a contract with Berns’ label Bang Records, and in a show of trust he’d rarely display in the future, he signed it without fully understanding the terms.

Read More: Top Ten Van Morrison Songs

The ramifications of this decision became clear relatively quickly. Morrison entered the studio in early 1967 to record eight songs that were ostensibly to be used for a series of singles, only to discover — much to his chagrin — that Berns opted instead to collect them all and release them as an album. According to Morrison, he only became aware of Blowin’ Your Mind!, which hit store shelves in the fall of 1967, when one of his friends told him they’d purchased it. In Johnny Rogan’s 2006 book Van Morrison: No Surrender, Morrison’s quoted as tersely saying he had a “different concept” for the material, which is an understatement; the album’s release presaged a period of increasingly aggressive arguments between the two, to the extent that when Berns died in December of ’67, his widow Ilene pointed the finger at Bang’s most loudly disgruntled artist.

“The unholy hell that was unleashed upon him when Bert died was really horrible,” recalled Morrison’s future wife Janet Planet in Clinton Heylin’s Can You Feel the Silence? Van Morrison, A New Biography. “Ilene was convinced that it was Van’s fault, that Van’s rancor had finally pushed him over the edge and he had the heart attack. And she vowed to… make sure that he’d never work again.”

Ilene Berns’ animosity manifested in several ways. According to Janet, Berns dug up a number of mistakes in the way Bang had handled Morrison’s work visa, and after determining he was in the United States illegally, she reported him to immigration. Faced with imminent deportation, Morrison married Janet. But that was far from the end of his battle with Bang.

For at least a little while, it seemed like his association with the label was behind him. In early 1968, he and Planet moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, reportedly to avoid the gaze of Carmine “Wassel” Denoia, a Bang associate whose efforts to keep Morrison in line included smashing a guitar over his head. By the summer of ’68, Morrison had attracted the attention of Warner Bros., who wanted him on their roster badly enough that label chief Joe Smith engaged in a mafia-style money drop that was supposed to free his new artist from his former label’s clutches. Bang wasn’t quite done with Morrison yet, however; the terms of his contract stated that he was not only obligated to re-record a pair of Bang-released cuts on his first Warners LP, but that he also owed Bang three dozen songs that would remain the property of the label.

Morrison fulfilled the first of those terms with Astral Weeks, which included the Bang-era cuts “Beside You” and “Madame George.” With that out of the way, he turned his focus to clearing the decks of the 36 songs he still owed Bang. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he had no intention of spending a lot of time or energy on the end results. Not only was Bang not going to get any of his best material, they wouldn’t even get anything that would be deemed worthy of release by any major label for decades to come.

Morrison’s contractual obligation sessions are frequently assumed to have been recorded in 1967, but as Ryan H. Walsh wrote for his My First Rodeo blog, there’s really no way that could be accurate. For one thing, Morrison references Boston in one song, and he didn’t live there until ’68; for another, Astral Weeks producer Lewis Merenstein is on record as having been in Morrison’s sphere during the period that produced those recordings.

“That was a very interesting experience,” producer Lewis Merenstein is quoted as saying in Can You Feel the Silence. “He got all of his grievances out at Bert Berns and Bang during that session.”

As anyone who’s heard the tapes can attest, Merenstein is both overselling and underselling them by calling the sessions “a very interesting experience.” Determined not to give Ilene Berns anything she could sell, Morrison essentially switched into stream-of-consciousness mode, dashing off a series of quasi-lyrical complaints set to music in extremely bite-sized chunks. Even by the abbreviated standards of the day, these songs are brief — the longest of the bunch, the starving artists’ lament “The Big Royalty Check,” clocks in at a minute and 36 seconds. Six of the songs are less than a minute in length. Throughout, Morrison vents his spleen — and perhaps other organs — at Bert and Ilene Berns.

Hear Van Morrison Perform ‘The Big Royalty Check’

Prior to signing Morrison, Bert Berns was a prolific and successful songwriter, whose credits include not only the Them hit “Here Comes the Night,” but enduring rock staples such as “Twist and Shout,” “Piece of My Heart,” “Cry to Me,” and “Hang on Sloopy.” None of that meant much to Morrison, at least not by the time he was at the mic for these tracks; as proof, one need look no further than the first five cuts recorded during this session, which are nose-thumbingly titled “Twist and Shake,” “Shake and Roll,” “Stomp and Scream,” “Scream and Holler,” and “Jump and Thump.” He also witheringly dismisses Berns’ choice for Morrison’s debut LP title with the songs “Blow in Your Nose” and “Nose in Your Blow.” On the song “Thirty Two,” Morrison mocks Berns’ production style, pretending to be the producer while he rants about triple-tracking guitars and finding background singers to “do the sha-la-la bit” on the Bang-era track “Brown Eyed Girl.”

Needless to say, Morrison’s jabs had the intended effect on more than one level. Most importantly for Morrison, they closed the door on his association with Bang; perhaps just as satisfyingly, they presented Ilene Berns with a pile of material that she not only couldn’t use, but couldn’t help but be heard as mean-spirited attacks against her deceased husband, the label, and herself. Calling the results “Bursts of nonsense music that weren’t really songs,” Berns said, “I just wanted to get on with my life, and so I didn’t bother to take him to court and sue him over the songs I didn’t get.”

Thus unencumbered from the contract that angered him so, Morrison quickly went on to write and record Moondance, the first commercial and critical hit of his young solo career. Bang, meanwhile, enjoyed its own success for a number of years; although the label lost future superstar Neil Diamond around the same time Morrison departed, notable future signings included Paul Davis (of “I Go Crazy” fame), R&B group Brick (the huge hit “Dazz”), and Peabo Bryson, who cut early material for the Bang subsidiary Bullet Records.

As for the contractual obligation sessions? Morrison’s dashed-off recordings remained officially unreleased for many years, although they were bootlegged so frequently that it was far from difficult to hear them. Few who did would have described the experience as essential, but as Morrison’s status grew, it reached the point where virtually any in-studio ephemera had commercial potential, and the tracks finally saw official release in 2017 as part of Legacy’s triple-disc Authorized Bang Collection.

Top 40 Unfinished or Unreleased Rock Albums

These projects didn’t quite make it to the finish line.

Gallery Credit: UCR Staff