W

e’re going to miss this show.”

I’m in the passenger seat of a new-model Mercedes that’s basically parked in Paris traffic. Steve Lacy sits in the back on aux duty, running through a playlist featuring the French electronic duo Air, M.I.A., and Faye Webster. We’re heading to the Bourse de Commerce, where Yves Saint Laurent’s Spring Summer 2026 presentation is about to start. Except, we’re not making very much progress. The journey from Lacy’s hotel to the venue should only take a few minutes, but we’ve been moving at the speed of dial-up. Our driver cuts down an alley, a ruelle in the local parlance, only to run into more gridlock. Making matters worse, a car emerges in the rearview, boxing us in. If we want to get to the show in time, we’ll have to walk. Fast.

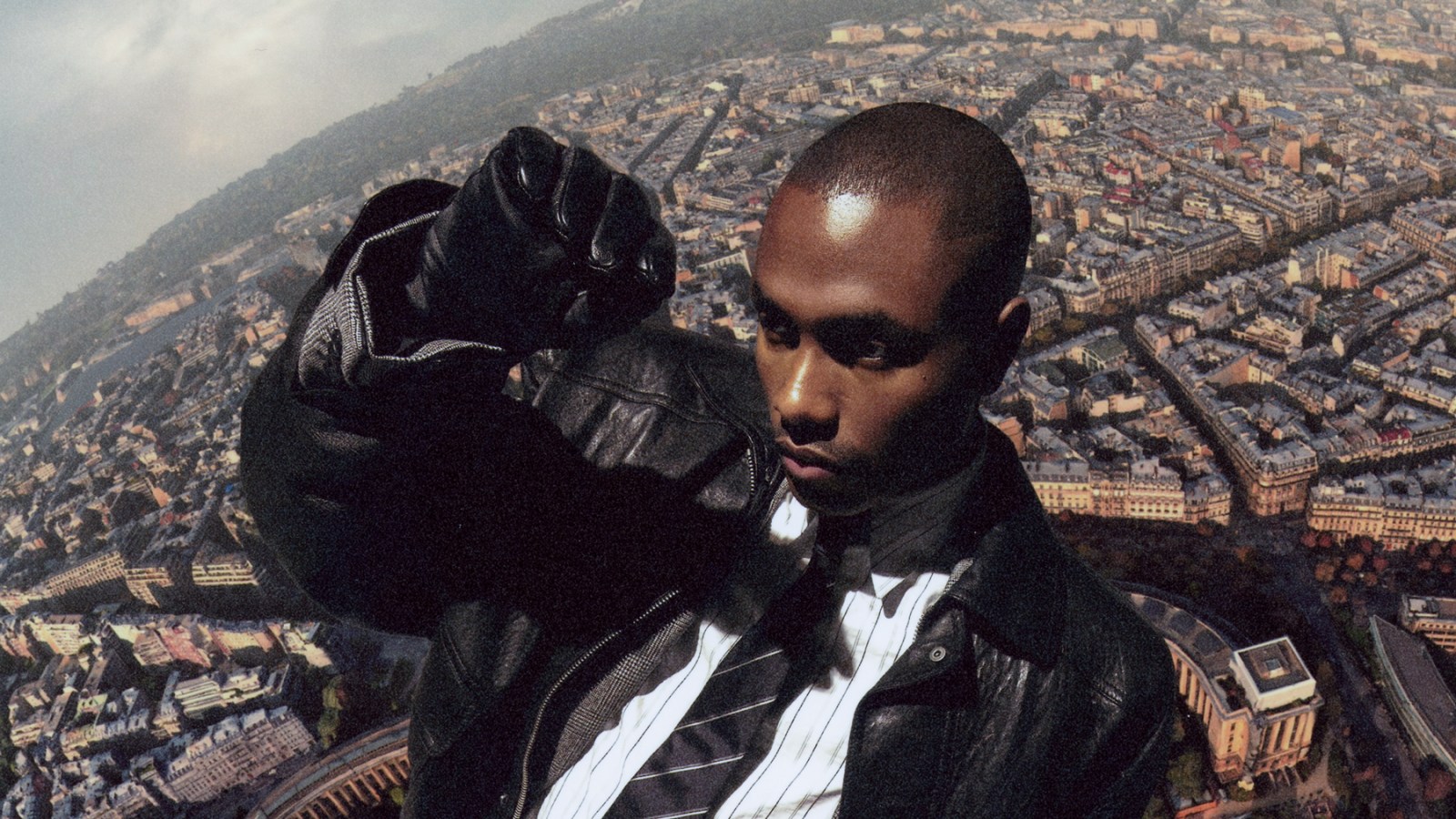

Lacy was named a brand ambassador for YSL back in 2023 and attends its menswear presentation, typically held in Paris, every year during fashion week. On this sweltering Tuesday afternoon in June, he wears a full YSL outfit replete with slim-fitting leather pants, tall black leather boots that almost serve as pants in their own right, and a crisp, white, geometrically tailored button-up, all from previous years’ collections.

Once our driver stops to let us out, Lacy bolts from the car in what appears to be a single, fluid motion. I notice a few necks crane in astonishment — your eyes are not deceiving you, that is indeed Grammy-winning musician Steve Lacy speed-walking down the streets of Paris in thigh-high Saint Laurent boots, looking exactly like a rock star.

Lacy is perhaps best known for his chart-topping 2022 single, “Bad Habit,” one of the first bona fide hits of the post-pandemic era. Everywhere you looked, swiped, or scrolled, you heard that chorus — “I bite my tongue, it’s a bad habit” — capturing the specific regret of not taking a chance with a crush. The song’s candidly self-deprecating hook — “I wish I knew you wanted me” — helped make it stick, connecting with something universal, even a bit profound, while maintaining a featherlight sense of levity. “That’s literally how conversations with me go,” Lacy says. “It’s like, a thought here and something profound there, and then a joke right after that.”

As the second single from his sophomore album, Gemini Rights, the track had an immediate, nearly alchemical quality. Its buoyant drums clomping beneath equally rambunctious guitar riffs hit like a scientific fact. It would be nominated for Song of the Year, Record of the Year, and Best Pop Solo Performance at the 2023 Grammys, along with Gemini Rights, for which Lacy won Best Progressive R&B Album.

Before he became a solo artist, Lacy, 27, made music as a member of the group the Internet, alongside singer-songwriter Syd and producer Matt Martians, who were then established names within the L.A.-based Odd Future collective. He served as co-executive producer on the group’s breakout album, Ego Death, which earned him his first Grammy nomination, in 2016, while he was still in high school. “I love the first thing I ever worked on being called Ego Death,” he says. “I came in egoless.”

The story of how Lacy’s career started is like something out of a VH1 biopic: A shy and talented teenager from Compton who’d lost his father to cancer meets a group of gifted young musicians who take him in and nurture his skills before he becomes a superstar. “When Steve was young, his mom was really protective of him. We were the only people that she trusted Steve to be out the house with when he was 15, 16,” Martians recalls. At some point during the Ego Death sessions, Martians needed a bass line for a track and asked to hear some of the music Lacy had been working on. “He started playing me a lot of the stuff that he had been making on his phone at the time. And I was blown away. I was like, ‘This is the type of music you make? This is insane,’ ” Martians says. “He was really shy. He didn’t realize how good he was.”

Cue the montage showing Lacy’s mastery of every instrument under the sun. Not only guitar, but drums, bass, and, as of late, synthesizers. Of course, he can sing, too. In the music video for “Playground,” from his debut album, Apollo XXI, he’s in a band composed entirely of other Steve Lacys, which seems fitting.

Shortly after the release of Ego Death, Lacy met Kendrick Lamar, who he would eventually work with on “Pride,” from Kendrick’s 2017 album, DAMN. Naturally, Lacy remembers his first encounter with the Pulitzer Prize-winning rapper in cinematic fashion. “I come in, I got all this shit on me, and Kendrick’s like, ‘I seen your face in some music videos,’ ” Lacy recalls. “I said, ‘Hey, yours too, man.’ And then he laughed.” Lacy timidly offered to play Lamar some of the music he’d been making at the time, and one of those tracks would go on to become “Pride,” which earlier this year joined “Bad Habit” and “Dark Red” on the list of Steve Lacy productions to top 1 billion streams on Spotify alone.

It was Gemini Rights that solidified Lacy among his generation’s greats. The album’s fluidity of genre — skating between funk, pop, rock, R&B, and hip-hop with the ease of a Spotify playlist — spoke to a cultural sensibility among Gen Z’ers, whose experience with music has so far been defined by infinite everything all of the time. The record also seemed to naturally strike a chord on TikTok, where in addition to “Bad Habit,” the album opener, “Static,” became ubiquitous as the go-to audio for the viral trend “English or Spanish,” where users stood stone frozen, backed by Lacy’s iconic opening lines — “Baby, you got something in your nose. Sniffin’ that K, did you fill the hole?”

“I find a lot of music today online and stuff. I don’t really believe in the whole attention-span conversation,” he says, referring to the belief that platforms like TikTok are depleting his generation’s ability to focus. “I think people gravitate toward the strongest moments of things.”

We arrive at the Bourse de Commerce — a concentric palace, once home to France’s open-air wheat exchange and now dedicated to the arts — in the nick of time, albeit at the wrong entrance. Korean pop star Cha Eun-woo draws squeals from the crowd of fans gathered out front, while security ushers Lacy through a small throng of civilians on the side of the building, up to where he’s supposed to have his photo taken. Once we get inside, greeted by artist Céleste Boursier-Mougenot’s installation “Clinamen,” featuring a basin filled with crystalline water and speckled with floating white ceramic bowls, it’s a flurry of double-cheek kisses and about three dozen “Hey, how are you’s?” Lacy flashes a mischievous grin and tells me he “might” have taken an edible earlier. “I don’t know if I did. Or if the edible took me,” he tells me after the show. I ask if having to walk to the event in 90-degree heat bothered him. “I don’t overthink these things.”

Nowadays, Lacy is mostly thinking about music. His new album, slated to drop in the near future, is called Oh Yeah? and features cover art that calls to mind a fictional beverage mascot known for bursting through walls. “I took his face out the glass. Hopefully I don’t get sued,” he jokes. Lacy’s been teasing the project in plain sight, wearing merch for the album in photos on his socials, all while fans clamor for new music. As for what inspired him to call his album Oh Yeah?, all Lacy says is “the question’s important.” For how tongue-in-cheek it all seems, the record is undoubtedly Lacy’s most confident work yet. “This one has taken a lot of time and thought,” he says. “I keep using the word ‘design.’ It feels like fully designing a new language for myself.”

“For a while, words were just kind of secondary. But now I’m like, ‘OK, I want to say shit how I would say shit.’ ”

Despite his penchant for memorable lines (“Dark Red,” opens with “Something bad is about to happen to me”), Lacy says this album marks the first time he’s consciously thought about lyrics. “When I first started making shit or producing stuff with the Internet, I would always make the beat, make a hook, and just give it away,” he says. “That was my process for a while, so words were always just kind of secondary. I’m like, ‘If my beat hard, this bass line hard, the chords hard, what else do we need?’ But now I’m like, ‘OK, I want to say shit how I would say shit.’ ”

The day before the YSL show, I’m in the car with Lacy, who is, of course, in charge of music, this time playing the latest version of songs from the album. We’re en route to a video shoot on the Seine, and along the way, we’re served an up-close view of Parisian landmarks like the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre, and Notre-Dame Cathedral. You get a fuller sense of music when listening in the contained private amphitheater of a good car stereo. The subtleties and texture in the vocals, the tactile rumble of drums, and the almost effervescent guitar melodies. The tracks I hear strike a personal, introspective tone, as if Lacy’s taken the perceptive and cunning lens he’s used to observe life and love from 10,000 feet, and turned it inward. He inhabits these songs emotionally, exploring themes around his racial identity, his relationship to love and trust, and his own sexual fluidity, all with the halfway comedic, occasionally devastating style of observation he’s built a career on. “I feel like I could just say shit, but also have little pokes at real human shit that you need to know and realize,” he says. “It’s a mix of stupid shit and real-ass bars.”

Lacy self-produced Oh Yeah? Sonically, the album is adventurous, diving into sounds like trip-hop and electronic while also building classic rock ballads fit for stadiums and arenas. In the past few years, Lacy’s taken an interest in synthesizers, which you can hear on his new songs. Famously, Lacy’s favorite band is Stereolab, and on his latest record he channels the Anglo-French group’s playfully melodic sensibility. The result is the type of all-encompassing pop album that artists like Prince (to whom Lacy is frequently compared) used to make. “When I heard the album, I said, ‘You really made a pop album. And not pop in the sense of current-day pop, but pop what it used to be as far as greats,’ ” Martians says. “He is getting into areas that I feel like are very reminiscent of a pop of yesteryear, which is very good.”

Lacy plays me “Nice Shoes,” which he describes as a “trailer” for this new moment in his career. He says he plans to release the song alongside this story — it’s out at midnight tonight, in fact. The track, as yet untitled, rides a drum-and-bass-style breakbeat that could best be described as filthy. The lyrics volley between playful and insightful, with Lacy musing on his dick getting hard at the thought of holding hands with his new crush — “romantic boners,” as he describes it to me — as well as the sometimes subtle nature of melancholy. “Crazy how you could be sad and not notice,” he sings. “All I need is my guitar and serotonin.”

Indeed, fans needn’t worry that Lacy has abandoned the guitar for electronics. Toward the song’s end, the bpm cuts in half, and he’s back on the six-string, plucking a quintessential Steve Lacy melody before his vocals glitch out, segueing into the break. Just like how he wants his lyrics to reflect the way he talks, Lacy is ready for his music to showcase parts of his personality and tastes he hasn’t let us in on yet.

BACK AT HIS hotel, in one of those tiny elevators that apparently plague the city of Paris, Lacy tells me how he’s become jaded about fashion week events. He finds the small talk and obligatory niceties draining. Also, he doesn’t quite see himself as a celebrity. Incidentally, that’s why he feels so comfortable in Paris, a city with a far less pervasive obsession with fame than most places in the U.S. Lacy’s been traveling to Paris on and off from his home in Los Angeles to record the album. The weekend before we meet, Lacy went to Beyoncé’s tour stop in the city (where Jay-Z would join her onstage for a Kanye-less rendition of “Ni**as in Paris”). He wasn’t backstage or in a VIP section, but in the crowd alongside his pal, musician Moses Sumney, whom he met at a pre-Grammy brunch around 2016. “We went as fans, took the train, we’re in the crowd, and I’m like, ‘In L.A. that would be crazy,’ ” he says. “But here, it was so cool and chill.”

“I don’t drink the Kool-Aid. I’m a student before anything.”

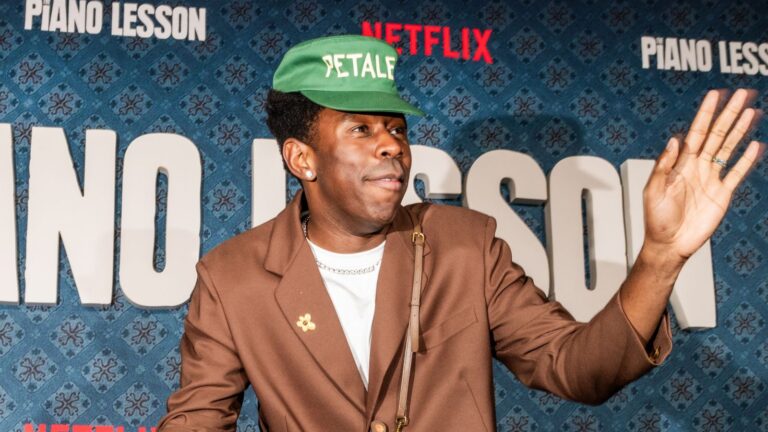

Lacy has mastered a kind of low-key fame, in which his fans are legitimately obsessed with him, and the music’s always good enough to make a splash in the mainstream — enough for him to get invited to fashion shows in Paris. He cites artists like Frank Ocean, Tyler, the Creator, and Solange as having the type of career he can see for himself. “They never conformed to the shape of pop music. But they can probably do whatever they want and headline whatever festival,” he says. “They all designed their own worlds, and people come to them.”

It’s par for the course among the current generation of superstars. Everywhere you look these days, the biggest names in music are looking to shed the artifice of celebrity in search of more authentic audience connections. It’s Charli XCX hosting raves, or Drake linking up with young streamers and content creators like Kai Cenat, or Justin Bieber’s new album, Swag, where he ditches his polished heartthrob image for a more unfiltered and down-to-earth persona influenced by his actual personal taste.

Lacy embodies this naturally, which often means treating fame more like an annoying sibling following him around than a fact of life. “I don’t drink the Kool-Aid because I’m a student first before anything,” he says. “I remember when I was first popping and people were talking crazy at me online. I remember bitching to my mom like, ‘Why the fuck is anybody bothering me? I just want to make music.’ She was like, ‘Steve, you’re blessed with this platform. You need to be grateful.’ ” Lacy says he’s been able to pass on that knowledge to up-and-coming stars like PinkPantheress, who said in an interview in i-D that he helped her navigate the sudden onset of viral fame. “Matt Martians was like that to me,” Lacy says. “So it’s cool that I can pay it forward and be that person for the other youngsters.”

In 2022, as “Bad Habit” reached peak virality, live venues began easing Covid restrictions, making for a long-awaited return of concerts. As he toured in support of Gemini Rights, Lacy went from being a relatively obscure act with a devoted fan base to a mainstream star with thousands of screaming teenage fans. He caught some heat after smashing a camera a fan threw onstage during one of his shows; a clip of the incident went viral. He brings up how many outlets got the facts of the story wrong. “That’s when I kind of understood what fame was,” he says. “The story was that I broke this [guy’s] phone and I ended the show. I was like, ‘Oh, wow. Niggas just lie.’ I finished the show. I was like, ‘Just make sure that person gets kicked out.’ Because why the fuck are you throwing shit at me?”

Going viral right at the start of his tour was a learning experience for Lacy. “It was a culture shock for me because I was so used to being niche, a cool music-nerd person,” he says. “I think going on the road post-Covid and going viral at the same time invited a lot of rambunctious kids who are going to concerts for the first time. So at first, my body rejected it. And then I think by the end, I was so happy with their rambunctiousness because I’m like, ‘Oh, this is their first show. I’m showing them how to be at a concert, so I want to embrace that energy myself.’ ”

After that tour, Lacy went relatively quiet, a move that’s somewhat atypical for an artist who just had a Number One hit and the biggest song of his career. “Anyone else in my position would be like, ‘Ride this wave,’ but I know I’m going to be here for a little bit. I ain’t worried about that shit,” he says. He sees vindication for his approach in the devotion of the Internet’s fans, who still obsess over clues around possible new music, seven years after their last album. (Lacy says the group has been “hanging out” and that we can expect new music soon.)

“Time is crazy, man, it really tells you. And I think this is why I feel so confident in my choices and my timing, because everything has been so slow and drawn out,” he says. “ ‘Dark Red’ went platinum five or six years later. So I don’t feel super stressed or entitled to quick virality. I remember even when I first signed to RCA, they were like, ‘So what do you want?’ I was like, ‘Man, I want to be as big as I should be. I don’t want to be bigger than I need to be.’ ”

Now, after scoring a chart-topping single and a Grammy-winning album, just how big should Steve Lacy be? Outside the YSL show, the 20-year-old singer-songwriter Sombr, real name Shane Michael Boose, comes up to Lacy and tells him he’s one of his heroes. You could say that Sombr is among the first artists to emerge from the generation most directly influenced by Lacy’s music. The budding pop sensation is having a Lacy-esque rise himself. In the past year, he’s nabbed two Top 40 singles, in part thanks to the hyperactive powers of TikTok’s algorithm. For his part, Lacy can sometimes feel unmoored by the age difference between him and some of his fans. “This one girl was like, ‘Man, we need the music. I had just graduated high school since the last thing came out,’ ” Lacy says. “I was like, ‘Why the fuck do you got to say it like that?’ ”

“My little ass was

gassed the fuck up.

I needed to be humbled.

It was good for me.”

One of the reasons Lacy wanted to attend the YSL show, beyond his love of the clothes, was to formally introduce his new hairstyle, a sharp, clean-cut fade, which he says is the first part of his new era. For years, he sported medium-length braids. “I always change my hair right after I’m done with some shit,” he says. “I couldn’t imagine what else I could do from those braids.” Lacy has the same barber as Tyler, the Creator, and ran into him at one of Tyler’s listening parties in Los Angeles last year, after spending several days contemplating the change. Taking the encounter as a sign, Lacy went ahead with the cut, though the transition was intense. “It was so emotional. I cried on the way,” he says.

Lacy has an easy, sun-soaked California cool. Even when dressed to the nines, he carries an air of comfortable grace, like a dancer. The haircut uncovers his face, chiseled and boyish, like a young Michael Jackson. Before he heads to the show’s afterparty, we stop for a drink at a nearby restaurant, where Lacy explains how he stopped smoking a few years back in service of his voice. A stoner at heart, he’s taken to edibles as his high of choice. It’s all part of a more intentional ethos that’s been guiding Lacy since the release of Gemini Rights. He says on this new album he “understand[s] energy more than I did on the last one.”

One theme that stands out on the album is romance — or a lack thereof. Lacy’s new music maintains his sly sense of humor, but with a barefaced melancholy that pushes it to new emotional depths. “I remember I was playing the songs for the label a couple of months ago,” Lacy says. “They were like, ‘All right, now play some happier ones.’ And I was like, ‘Fuck.’ ” He attributes much of the doom and gloom of those early tracks to a breakup last fall that, for a while, had him reevaluating his relationship to love.

Thankfully for Lacy — and the label — he has been making happier songs, too. Lately, in fact, he’s feeling very romantic. A few weeks before he left for Paris, he met someone. They met “how the kids meet,” he says coyly, by which he means “digitally.”

“On our third date, it was his birthday, and he wanted to see me, and he was with all of his friends rolling deep as fuck with maybe eight or nine people,” Lacy recalls. “I’ve stopped talking to people I was dating because they wanted me to hang out with their friends, but with him, I met all his friends, and I even hosted the afters for him. That’s how I know I’m crushing hard, because I don’t do that shit for anyone.” Lacy’s ex was even seated near him at the YSL show, though he was emotionally prepared this time as opposed to last year, where their presence at the same event arrived like a “jump scare.” He partially credits his new romance with his current sense of peace with the situation.

He’s found a renewed love for music as well. On one of his trips to Paris this year, he found a particular guitar that managed to rekindle his passion for the instrument. Up to then, Lacy had been feeling like the sound was becoming cliché. “I went to Paris, and I bought this Gibson from 1990, and it’s got me playing guitar again, so that’s pretty exciting,” he says. “For a while, I was just on this synth and on my bass, but I feel like a rock star again, a guitar rock star.”

LACY WAS BORN in Compton, the California city he describes as equal parts magical and misunderstood. “I don’t have to worry about putting Compton on the map,” he says, citing the city’s history of producing legendary artists. “There’s a lot of negative stuff, but there’s also so much positive stuff to come out of the city.”

Lacy’s mother is Black, and his dad was Filipino. They met at work — Lacy’s mom was a nurse and his father was a handyman at the hospital where she worked — before getting married and having two kids, Steve and his younger sister. (His mother had two daughters from a previous marriage.) Lacy’s parents split when he was young, and when he was 10, his father died of lung cancer. He says he never got to engage much culturally with his dad’s side of his identity. “It’s slipped away from me,” he says. “I have to rely on stories of loved ones to give me more information.”

“I grew up around lots of death. It affects the way I treat life.”

Growing up in Compton with identifiably Black features, Lacy remembers friends asking him who his dad was. “When I was younger, I just looked Black,” he says. “My Filipino features came in as I got older. So I was like, ‘Somebody’s lying to me. Who the fuck is this man picking up my sister and I?’ ”

Lacy only saw his father sporadically growing up, so when he died, Lacy was unsure how to feel. He remembers crying once. “It was so abstract to me. I remember questioning how sad I could be with someone who was so occasional,” he says. “And then as I grew up, I understood that there are just things that you learn from your father that I just don’t have. I think the saddest part is kind of just finding out for yourself what those things are. But he still be around, though. I got a relationship with the dead. I feel him sometimes.”

Having family overseas taught Lacy about different levels of poverty around the globe. Even after his father died, his mom would send money to his family in the Philippines. “We grew up in a three-bedroom with one bathroom, and we would pass up on McDonald’s,” he explains. “She was still communicating with [his family] via Facebook and sending MoneyGram for like 50 bucks. She’s like, ‘In the Philippines, you’re rich, so you got to remember that.’ ” Lacy mentions never seeing his parents show intimacy. He sees his current relationships as “trying to, like, correct their wrongs somehow. I guess I just want to prove to myself that I’m not them.”

Lacy comes from a musical family. His mother was once an aspiring singer and has sung background vocals on Lacy’s songs, along with his sisters. When he was around 10 years old, Lacy started playing guitar after watching the band in his church. “At the end of the service, they would just shred, and I would sit there and watch with my jaw to the floor, not moving,” he says. By then, he’d already become enamored with the guitar thanks to hours playing Guitar Hero. “When I was 10, I was obsessed with the instrument. I wanted to touch it. I wanted to be around it. I wanted to hear it,” he says. Before long, he’d start lessons.

When Lacy was in high school, his mother encouraged him to join the jazz band, which he did. Around 2012, his friend and classmate Jameel Bruner (Thundercat’s younger brother) would fatefully introduce him to Matt Martians and the rest of the Internet, just as Odd Future started taking off. He started hanging around the bandmates, who were all much older than him, as they rehearsed. “It’s kind of like the first freedom I got as a teenager because I grew up super sheltered. But my mom started to let me chill a little bit. I would go there, just watching. And I was really quiet. They called me Lil Steve.” (“I literally just changed his contact in my phone a couple months ago from ‘Lil Steve,’ ” Syd tells me.)

Martians wanted to ensure that Lacy was well positioned to launch his own career. “I would start telling him, ‘Look, we need to put together an album. Doesn’t have to be long, doesn’t have to be crazy, convoluted, but the world needs to be presented you by yourself,’ which is why on Ego Death, he’s in the band, but I chose to put him as a feature on ‘Palace/Curse.’ I wanted to set up that transition to him being known as his own entity.”

In 2017, right before he turned 19, he released Steve Lacy’s Demo, recorded largely using GarageBand on a beat-up iPhone. Even early on, his songwriting skills stood out. Demo includes the sleeper hit “Dark Red,” a bouncy earworm that to date has racked up nearly 2 billion streams on Spotify alone and feels almost like a precursor to the equally infectious “Bad Habit.”

John Troutman, chair of the Smithsonian’s division of culture and the arts, heard about how Lacy recorded the EP after reading about it in Wired. “It sounded like one of those stories that is just so incredible on so many different levels because it reflects his extraordinary talent at such a young age musically and as a producer,” Troutman says.

Troutman and his team were putting together an exhibit called “Entertainment Nation,” and they reached out to Lacy in 2017 to acquire the legendary iPhone. The show opened in 2022. “We opened right when ‘Bad Habit’ was top of the charts, so the young folks who came through knew exactly who he was and were so surprised and delighted to see the iPhone,” says Krystal Klingenberg, a curator at the Smithsonian.

“We’ve seen teenagers bowing down in front of his phone,” Troutman adds.

In 2019, Lacy sang about his queer identity for the first time, on his debut studio album, Apollo XXI. On “Like Me” he opens with a sort of preamble: “This is about me and what I am/I didn’t wanna make it a big deal/But I did wanna make a song.”

Lacy says he “kind of waited” to come out. “I hid everything until I started doing things,” he says. “For example, I really love dance, all styles, contemporary, tap, hip-hop. I love modern dance. But growing up, I couldn’t explore that ’cause I never wanted anyone to call me gay before I told them I was anything, gay or whatever, you know? It’d probably be easier if it were just like, ‘I’m g-word,’ but I’m not g-word. It’s fluid, and queer is a lot harder to explain than just being a gay dude.”

“For a while, I was just on this synth and on my bass, but I feel like a rock star again, a guitar rock star.”

Lacy maintains a mischievous relationship with social media. He’s liberal with how much he posts to his main feed on Instagram, and he’ll occasionally pop out on TikTok, posting clips using current trends or showing up in videos with popular creators. And though he hasn’t been doing it so much lately, Lacy’s also known to clap back in the comments. Before officially coming out, fans on Tumblr and Twitter had already put together that he was queer. After a since-deleted tweet about racial dating preferences, a full-blown hate train emerged. Lacy says he learned from the experience. “I appreciate it now, I understand where it’s coming from, and I have empathy for it,” he says. “I remember at the time it was really hard to hear,” he says.

“I was just 18, that’s how I came out, bro,” he says. “People found out about me kissing boys and girls from me getting canceled. But I needed that because my shit was too perfect. My little ass was gassed the fuck up. So I needed to be humbled. It was good for me.” As a queer Black artist, Lacy is cautious not to position himself as any kind of spokesperson. For Lacy, it’s more important that all shades of experience see the light of day. “I feel like my whole mission is the humanization of Black people,” he says. “We have so many spectrums of emotions. I think it’s so limited when it comes to what we can watch and ingest.”

That idea is part of what made Kendrick Lamar’s Pop-Out concert so special for Lacy, who appeared onstage alongside a host of West Coast rappers. “That was so beautiful and profound because I think when you’re in Compton, you only see one type of music being blasted. So I never expected what I was doing to be respected or a part of the conversation of what Compton is,” he says. “So to be there and to feel that love and to be amongst other artists from Compton, who are doing the thing that Compton is too, was very special.”

Though his appearance at the event seemingly miffed Drake, who called him a “fragile opp” (something akin to being an enemy) on a stream with xQc last year, Lacy says he found the comment endearing: “I love Drake; I grew up listening to Drake and shit.”

A word that comes up a lot in our conversation is “fluid.” I get the impression that very little remains fixed with Lacy. “I love how my fluidity has just felt through the music,” he says. “I feel like a lot of people use the gay bug to market their shit. And I never did.” Music allows Lacy to express all of the different parts of himself. “It helps me form an identity somehow. Like the story writes itself, you know?” He says his favorite song of his is “Static,” from Gemini Rights, “because it was so honest.” The song finds Lacy unfiltered about his romantic frustrations. “Lookin’ for a bitch, ’cause I’m over boys,” he sings.

“I was so pissed off when I wrote that song, and I remember listening to it back, and I was like, it feels like when you’re so mad you want to cry.” His new music, he says, is fueled by the same level of transparency, “but more.” “I’m like, I want more emotion, raw emotion. And I want to just say it to you directly.”

“I think he’s always been very open,” Syd says. “I think that’s one of his superpowers. His ability to be himself no matter what anybody else thinks.”

Some of Lacy’s directness comes from his relationship with death. “I grew up around lots of death,” he says, citing not just his father but also the violence in his neighborhood. “I think it affects the way that I treat life and people. I don’t feel so entitled to people’s time. I just kind of want to make the most of it.”

After Lacy heads to the YSL afterparty (I’m not invited), I meet up with a friend in town and head to a party hosted by a local gallery. As it happens, I run into Lacy there. He tells me the official afterparty was boring and seems to be enjoying this function, a far more low-key affair, much more. He mentions he’s now run into two exes on this Paris trip — the one from last fall and his first ex, from when he was 19. Not only that, but these two exes have apparently become friends. (He jokes later about “putting that dick on the map.”) It’s a scenario that would send me running for the Seine, but one that seems not to bother Lacy, as he exchanges friendly conversations with both.

“I love how my fluidity is just felt through the music. I feel like a lot of people use the gay bug to market their shit. And I never did.”

It’s a little after midnight, and the party has migrated from the sweaty dance floor to the sidewalk, where cigarettes and nondescript party favors exchange hands with clandestine rhythm. Lacy greets me with a hug, though I can tell he’s being careful not to get too loose in front of a journalist. “You’re gonna be a part of this moment, you know,” he tells me. I joke with him about the lyrics to his new song: “If there were ever a time to let it out, it’d be now.” He sings the unreleased lyrics in a stirringly perfect pitch before someone taps him on the shoulder to chat.

The next day, we’re back in Paris traffic, this time headed to L’art de L’automobile, a private garage that’s more like a winding concrete shrine to classic sports cars. It’s owned by Lacy’s friend Arthur Karakoumouchian, known among artists as a purveyor of the finest and rarest European sports cars. The two had a mutual friend in the late designer Virgil Abloh, whom Lacy met at an Apple event before walking in Abloh’s first Louis Vuitton show. (“I had a sad realization the other day,” he remembers. “The only gift that I ever got from Virgil was a clock that went backwards.”)

While not totally a car guy, Lacy has an affinity for Porsches and remembers driving a Tesla when he got into an accident back in 2020. Living in Topanga at the time, Lacy was navigating a curve when a drunk driver hit him head-on. “They were coming in my fucking lane, bro,” he recalls. “I had a thought, ‘Man, we put so much trust in these lines in between us.’ ” Lacy, thankfully, wasn’t hurt, but “saw the black flash,” he says. “It was intense, and my brain was going so many different places. I remember afterwards being like, ‘If you were to die in that moment, would you have been satisfied with everything?’ And I remember being like, ‘I think the only thing I would’ve changed was I want to be more transparent.’ That was my only note for myself.”

This reminds me of something he told me earlier that day, about the time he met Jay-Z, not long ago. They were backstage at an event and Jay was watching one of his kids, halfway paying attention to the people around him. “I have nephews and stuff, so I know when I’m bored with adults, I’m going to focus on the kid, you know? He was kind of doing that — watching the kid, but sitting around. And no one’s talking to him. So I’m like, ‘I’m about to go sit and talk to Jay-Z.’ ”

Does Jay-Z know who Steve Lacy is?

“I don’t know. I don’t think he did. So, I’m talking to him: ‘How you doing, man?’ He was like, ‘I’m good, chilling.’ I was like, ‘I like your fit. What’s that jacket?’ He’s like, ‘The Row.’ I was like, ‘Oh, shit,’ and I showed him I’m also wearing the Row. I’m stoned also, but off the ones that make me talky.”

Like any stoned person would in the presence of hip-hop royalty, Lacy decided to break the ice with a joke. “I was like, ‘Man, it’s fucked up you didn’t book Lil Wayne in New Orleans at the Super Bowl.’ He’s like, ‘Nah, it was all there. It would be crazy not to have Kendrick, you know?’ And I was like, ‘Nah, I know. I’m just fucking with you.’ ”

So far, so good.

Feeling emboldened, Lacy mentioned one of his favorite Jay albums: “I told him I love 4:44. He’s like, ‘Man, I’m happy you brought it up.’ Then I was like, ‘Man, you a cool dude, bro.’ Then after I walked away, I was like, ‘Why the fuck did I just tell Jay-Z he’s a cool dude?’ ”

It’s the type of transparency you get with Steve Lacy these days. You can be sure that whatever he’s saying, he really means it.

Production Credits

Produced by CHIARA LAFOUR and ZOE ARICH for LAFOUR STUDIOS. Styling By KK OBIE At CLM-AGENCY. Grooming by ALEXA HERNANDEZ At THE WALL GROUP. Set Design By FELIX GESNOUIN at TOTAL WORLD. CGI MAKY. Video Director of Photography CHARLES DEVOYER for BFA. Camera operator: LAURENT GANIAGE for BFA. Videographer ETIENNE H. BAUSSAN. Video Editor: RYAN JEFFREY. Photographic assistance KAI CEM NARIN, MATHIEU BOUTANG, SCOTT GALLAGHER and PAUL MERELLE. Digital Technician ROMAIN BOE. Production Assistance GERMAIN CESENA, AUDREY GUYON and MARTIN DWERNICKI. Production Intern DUNE ALLANTE. Styling Assistance ALISA DATSENKO and LIBAN ALI. Set Design Assistance ELIJAH DEROCHE. Boat PARIS YACHT MARINA