For a lot of artists, achieving a big commercial breakthrough can have a paralyzing effect. With the stakes suddenly higher, it’s often difficult to plot your next move, and as a result, subsequent releases can feel watered down and tentative.

This was never the case with Prince.

In the years immediately following his watershed success with 1984’s Purple Rain, Prince released a series of records that found him continuing to stubbornly follow his muse. He seemed to willfully subvert expectations while deconstructing his own stardom with that record’s rapid-fire follow-up, Around the World in a Day, setting the tone for the rest of the decade.

Whether he was dabbling in sparse funk and psychedelia (Parade), hopscotching between genres (Sign O’ the Times), getting spiritual (Lovesexy), or going Hollywood (Batman), the only constant in this string of releases was that none of them looked or sounded like the Purple Rain sequel that label execs — and more than a few fans — were undoubtedly hungry for. And then, just when people least expected it, he delivered his version of Purple Rain II.

Of course, in true Prince fashion, it offered little of anything that description might lead a person to expect.

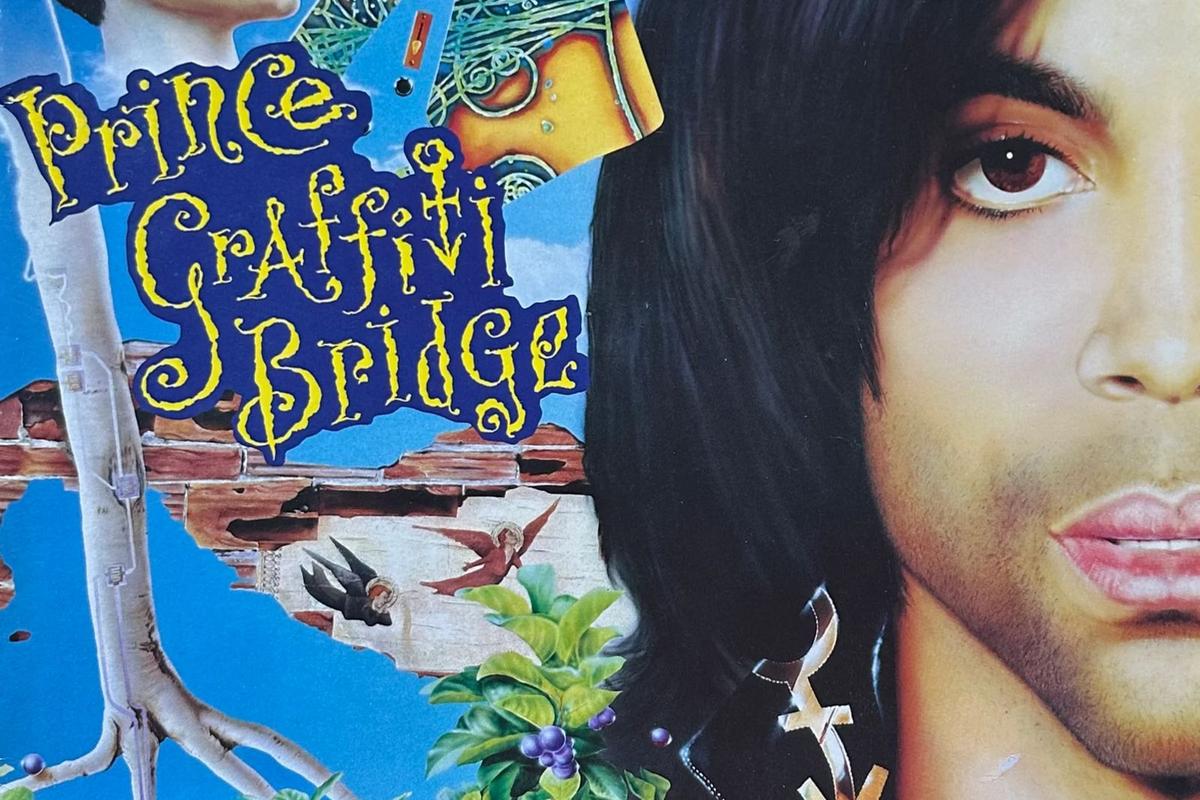

Released on August 20, 1990, Graffiti Bridge took a long road toward completion. Like Purple Rain and 1986’s Parade/Under the Cherry Moon, it was conceived as a film/album project, but it went through a number of changes between concept and execution — among the most intriguing of which was the brief period when Prince considered casting and collaborating with Madonna. It didn’t pan out.

“I went to his studio in Minnesota and worked on some stuff, just to get the feel of what it would be like to collaborate. Prince and I didn’t really finish anything, though,” she told Rolling Stone in 1989. “We worked for a few days; then I had to leave to do some other things. I decided that I didn’t want to do a musical with him at that time.”

Read More: 68 Forgotten Rock Supergroups

Later, Prince considered pivoting toward a story that would focus on the reunited Time, with Prince directing but not starring; when a deal for that proved impossible to work out, he directed his new reps to pitch it to Warner Bros. as a Purple Rain sequel, which finally did the trick. At that point, the only thing he had to do was come up with a workable script.

As one might imagine given all the twists and turns it’d taken to get to this point, that proved easier said than done. After hammering out a treatment with actor Kim Basinger during their brief post-Batman affair, Prince settled on a story that found his Purple Rain character, the Kid, locking horns once more with his Rain rival Morris (Morris Day). This time out, instead of a love interest who had to purify herself in the waters of Lake Minnetonka, the Kid had his eyes on Aura (Ingrid Chavez), a literal angel who often appeared as a floating feather.

As with the first film, the narrative went hand in glove with the music, with the latter emphasized more heavily than the former. The difference this time was that the story and the soundtrack were both far less consistent or coherent.

Where the soundtrack was concerned, this was partly by design. Of the 17 tracks on the album, five were led by a featured artist other than Prince, and for the most part, the songs were pulled from his vaults and updated in various ways. Of course, the material in Prince’s archives was often head and shoulders above anything any given artist might write specifically for a particular record, but this process still reflected the nature of the project.

The film was another story. With Prince directing himself and working from a script he’d written, the odds of creative blind spots were high; no matter how talented an individual might be, when you’re talking about something with as many moving parts as a movie, checks and balances are almost always beneficial.

Seeking to put some sort of guardrail around their mercurial director/star, the studio dispatched executive producer Peter MacDonald to the set — a move that made some sense, considering that he’d already looked over the shoulders of Barbra Streisand and Sylvester Stallone on projects they’d directed and starred in. While admitting they clashed at times, MacDonald had only good things to say about Prince’s work ethic.

“I’ve learned things from Prince,” MacDonald told the Minnesota Star Tribune. “It’s been a challenge to stay just behind him. His energy — it never seems to run out, unfortunately. I’d like for him to get tired a bit more often so we can go home.”

On the other hand, that indefatigable energy paid off in the long run; as the same article notes, Graffiti Bridge — which contains over a dozen musical numbers — was shot in a little over a month. “I know why Hollywood never makes musicals anymore: they’re too hard,” admitted another of the film’s producers, Craig Laurence Rice. “Films are like wars. I think we’ve won this one.”

The public disagreed. When the Graffiti Bridge album arrived in stores, the movie was still months away, which didn’t help anybody trying to spot a through line between the songs; the record still peaked inside the Top Ten and spun off a pair of hits with “Thieves in the Temple” and “Round and Round” (the latter of which was credited to its lead singer, the teenaged Tevin Campbell), it ended up being Prince’s first LP since 1980’s Dirty Mind to fall short of platinum status.

Critics, meanwhile, heard a messy summation of everything Prince had done during the previous decade — a set of songs worth checking out, but not necessarily falling in love with.

“Since the mid-1980s, Prince has been toying with harmony and texture, seeing how many eccentric add-ons he can get away with,” wrote Jon Pareles for the New York Times. “Songs sometimes grew too wispy and cute in the process, but now he has found a balance.”

The Boston Globe, on the other hand, called it “less a masterful concept album than an oft-scintillating, sometimes puzzling, collection of thematically linked bits and pieces. It’s a jumble of genres, compacted with a pulse and some wit. A pastiche of more and less.”

The Graffiti Bridge soundtrack was still in the midst of its six-month chart run when the movie reached theaters — and the film reviews did not help sales, to put it mildly. The Graffiti Bridge movie was roundly savaged by critics, who acknowledged his incredible talent while vociferously arguing that he needed to stick to the recording studio.

Saying Prince’s “quest to reconcile his carnal and spiritual sides has become obsessive,” the Chicago Tribune‘s Mark Caro wrote, “Although Prince is a crackpot, he’s a fascinating and immensely talented one — even if his talent does not extend into coherent filmmaking.”

“The songs in Graffiti Bridge are by and large inferior to those in Purple Rain and the gruel-weak story is an excuse to stitch together some splashy music video sequences,” wrote film critic Cary Darling. “Chavez’s acting is just two steps removed from catatonia, while Day’s once-charming showboat of a character is now just obnoxious.”

Ultimately, the whole project was regarded as a misstep for Prince. And like most of his missteps, it was quickly paved over by his next album — in this case, Diamonds and Pearls, widely regarded as a return to form when it arrived the following October. Further following his usual form, Prince refused to regard Graffiti Bridge as a failure, arguing that anyone who didn’t like it just didn’t get it.

“I can’t please everybody,” he told Rolling Stone. “I didn’t want to make Die Hard 4. But I’m also not looking to be Francis Ford Coppola. I see this more like those 1950s rock & roll movies. Some might not get it. But people also said Purple Rain was unreleasable. And now I drive to work each morning to my own big studio.”

Still, even Prince had to acknowledge that his own remarkable creative output was sometimes his biggest obstacle to delivering focused work. It didn’t mean he was going to change his ways — at least not anytime soon — but it was a point he was willing to concede.

“One of these days,” he chuckled, “I’m going to work on just one project, and take my time.”

Prince Year by Year: 1977-2016 Photographs

The prolific, genre-blending musician’s fashion sense evolved just as often as his music during his four decades in the public eye.

Gallery Credit: Matthew Wilkening