T

he members of Geese are sitting around a hibachi grill at a Brooklyn restaurant, talking about the time they lost an entire day in the studio listening to handclaps. While making their new album, Getting Killed, they wanted to incorporate the sound onto a track. So their producer, Kenneth Blume (better known as Kenny Beats), promptly opened a folder of sample files.

“He pulled up 7,000 claps,” frontman Cameron Winter recalls. “We spent all day choosing a clap.”

Even months later, Winter, drummer Max Bassin, guitarist Emily Green, and bassist Dominic DiGesu are still incredulous as they recall the intensity with which they conducted this search. And its ultimate futility.

“That was one of the days we went home sad,” Green says.

Why? “We spent too long looking at claps!” she answers.

“We forgot to make the song,” says Winter.

“You think you’re gonna make a song, and then the day ends and it’s like, ‘Let’s hear what we got,’” Bassin says. “And it’s a clap.”

The restaurant, in the upscale, home-y neighborhood of Park Slope, isn’t far from where several members of Geese grew up and first started playing music together at an after-school rock program. Now all in their early twenties, they formed the band in 2016, when everyone was still in high school; college was deferred after their early demos sparked a bidding war among several top-tier indie labels. Geese were quickly pegged as NYC wunderkinds, and have since earned a reputation as one of the most original young bands out there.

Their proper debut, 2021’s Projector, was a buzzy collection of post-punk pastiche; 2023’s 3D Country was an assured swerve into inventive yet familiar rock & roll. Support runs for King Gizzard and the Wizard Lizard, Greta Van Fleet, and Vampire Weekend bolstered an already avid fanbase. As did the surprise success of Winter’s phenomenal solo debut, the more subdued Heavy Metal, released late last year.

Getting Killed, out Sept. 26, is Geese’s most formidable album yet. DiGesu and Bassin cut deeper, craggier grooves. Green swings her guitar between halcyon and haywire, and Winter sings — he just flat-out sings, a nimble and mighty vocal contortionist with one of the most distinct voices in music.

“They’ve been put in this jam-band space. They’ve been put in this ‘smart kids in New York who play instruments good’ space,” Blume says. “They’ve been branded in all of these different ways. And they really wanted to say something different with this music.”

But as self-assured as this record often sounds, the empty toiling of hand-clap day shows just how different everything was when Geese flew to Los Angeles in early January to record with Blume, who’s produced several rock records but is still best known for his work with rappers like Vince Staples, Denzel Curry, and Rico Nasty. The band arrived in his studio with about 20 demos, but few resembled full songs. Blume says he could hear in them a “huge shift in texture, ambiance, and purpose,” but it was far from clear how they could actualize it all. For a group driven by a creative restlessness, a desire to distinguish themselves from both predecessor and peer, Geese felt woefully underprepared. Completely directionless. Also, Los Angeles was on fire.

“As stressed as they were about making a great record,” Blume says, “add this on top of it, it wasn’t easy.”

For a full month, Geese trekked back and forth between their shared home in Mid City and Blume’s studio near the University of Southern California. There was little to do but work. They weren’t particularly close to the fires, but smoke choked the skies and the open-air atrium Blume had built into the studio was covered in dust and ash.

True New Yorkers, no one in Geese has a driver’s license. And L.A. isn’t exactly a walkable city, as many stranded East Coasters have learned before.

“The amount of steps I got daily was atrocious,” Green deadpans.

“Oh, buddy, it was great,” Bassin says. “I love Uber.”

When Winter wanted to get to the studio early, he took the bus and even developed a fondness for L.A.’s much-maligned public transit. “It was better than the New York bus,” he argues, “because it has these little screens at the station telling you when it’s gonna come.”

The chef lights the onion volcano and spurs the flame with spurts of oil from a bottle shaped like a pissing baby. Hibachi, go figure, is not particularly conducive to in-depth interviews, but it’s not a bad place to observe a band of friends. Bassin and Winter tend to be the most talkative; the drummer is blunt and boisterous, the singer more measured with both his sincerity and sarcasm. DiGesu is quiet, but keen when he speaks, and Green balances her candor with a wry reserve.

They all have that slouchy, effortless aura so fitting for a New York band. During the meal, they get distracted by Jeopardy! questions on the TV and follow tangents on topics such as sashimi vending machines in Japan and ASMR-style videos of dirty rugs getting cleaned. When it comes to music, Geese are open, frank, and considered, at least when they want to be.

Making Getting Killed wasn’t easy, Winter admits. “I was unhappy until the last possible moment,” he says. “Maybe even still. The whole process — maybe this is just how we make albums — but it’s all kind of a waking nightmare until it’s mastered.”

“It does feel like a brute-force effort until the very end,” Green adds.

And then a few minutes later, Winter’s joking about how, if they ever want to make a triumphant comeback album, they have to start “making dogshit quick.” He adds: “We just do it for the ‘critical reception’ part of the Wikipedia article.”

“That and the fucking snacks, dude,” Bassin says.

ROCK & ROLL HAS been around for so long, endured so many deaths, that even its most striking revivals can resemble grave robberies. The risks of tumbling into that pit — a literal nostalgia trap — are high. Geese have garnered comparisons to Television and Zeppelin, the Strokes and the Stones, Deep Purple and Gang of Four, just to name a few. But like rock’s best crooks, they are beginning to excel at leaving a trail of tantalizing clues while always getting away with the heist.

“For a band that reminds people of so many acts they were really trying to combat nostalgia in certain ways, without having to say that,” Blume tells me.

Loren Humphrey, a close studio collaborator of Geese who co-produced Winter’s solo album, echoes the sentiment. “They’re really passionate about trying to do something different,” he says. “A lot of the artists that I’ve worked with, or even just sessions that I’ve been around, all of the production seems so referential. Like, ‘Let’s make the drum sound exactly like this.’ It was cool to see these kids coming and it’s the opposite. They don’t want to reference anything.”

Blume, too, mentions Geese’s aversion to nostalgia while discussing the way they incorporated samples on Getting Killed, like the auxiliary production clattering off Bassin’s drums in “Taxes” and the chopped loop of a Ukrainian choir ululating over crunchy guitar riffs on “Getting Killed” (though not, sadly, handclaps).

“They wanted these samples not to reinforce music that was already there,” Blume says. “It was almost to fight against it.”

This allure towards the vanguard feels linked to the way Geese came up in New York City. Everyone in the band attended progressive schools like Brooklyn Friends and the Little Red School House, and many grew up in households filled with music. Green’s dad is an accomplished sound designer and Bassin’s father, who died when he was eight, worked at the Alternative Distribution Alliance, the indie distribution wing of Warner Music. Winter has spoken about how his father — a professional composer who oversees a production music library — gave him old recording equipment to play with as a kid, as well as “brutal” but constructive criticism on the songs he then made.

As teenagers, they all joined after-school music programs where they were trained on the classic rock canon and encouraged to write their own tunes. The earliest Geese practices and recording sessions took place in Bassin’s basement. Between 2018 and 2019, they self-released an album and two EPs, and while all have since been scrubbed from the web, it’s an output that suggests an impressive determination and drive for high school students.

Not that Geese remember it that way. They say they worked slowly, in a haze of weed smoke and Mario Party marathons. They blew some money on a projector and hooked it up to a Wii; if they hadn’t, Winter cracks, they “probably would’ve made three albums.” Still, he adds, the band “learned a lot,” and by the time they started making Projector, Geese were turning out nearly a song a week.

Tim Putnam, president and co-founder of Partisan Records, the label that signed Geese in 2020, remembers them during these days as “young, but deliberate.”

“It was obvious how fast they were going to evolve artistically once we started working together; however, I didn’t yet understand how prolific a songwriter Cameron was, who consistently writes so far ahead of the curve,” he says via email. “The creative leap from Projector to 3D Country (which has continued on Getting Killed) was pretty staggering.”

It’s not that Geese don’t sound like Geese on that first widely released album, but it’s striking how different it is from everything they’ve made since. “We didn’t think anyone was gonna hear it,” Winter says, “so we got really into talk-y post-punk, which is already a rip off of the Fall and stuff like that. Not that it’s bad. But we just did a fucking facsimile of a copy of a goddamn ripoff.”

When I ask about their aversion to so clearly citing their sources, Bassin throws up his hands. “Fucking everyone’s telling us we’re fucking ‘Greta Van Fleet if they did it right.’ And it’s like, ‘Yo, what are you listening to?’” (To be clear, this seems less like a dig at their old tourmates than a shot at anyone wanting to rag on GVF.)

“A lot of 3D Country was running as far away from what we did before, because we were disgusted with ourselves,” Winter adds, running with the bit. “We decided, ‘This won’t stand. We have to rip off different music!’”

So who were they ripping off most on Getting Killed?

Bassin pauses: “Uhh, Beethoven, mostly.”

“Ravel,” Winter says.

“Been listening to a lot of Goose recently,” quips Bassin. (This one is certainly a jokey dig at the popular jam band with the confusingly similar name.)

Winter cites a few fictional acts for good measure — Cheese Boys, Cornbread Sally — but in the middle of the riffing, Green offers a genuine answer: Heavy Metal.

Geese onstage at Music Hall of Williamsburg in December 2024.

Griffin Lotz

WINTER BEGAN WORKING on his solo debut in July 2023, just one month after 3D Country was released, but also in the thick of what was a long, fallow period for the band. “Our lost weekend,” he jokes.

They’d recorded most of 3D Country in the first half of 2022. After it was finished, Geese toured a bunch, but also spent a lot of time hanging around at home. Bassin played video games. DiGesu worked at a restaurant. Green took a few classes at Columbia. Winter started to write his solo songs.

“I was depressed,” he says. “There was just not much going on. 3D Country hadn’t come out, so very few people gave a shit about the band. We had nothing to show for a lot of the tours we’d been doing. Or just not enough in my mind. I tried to make a point of going in and making songs.”

He worked on the album through the summer of 2023, reuniting with Humphrey over the ensuing months to complete it in between tour dates. Winter has crafted little legends around Heavy Metal, claiming it was partially recorded at Guitar Centers around NYC with a five-year-old bassist and a steelworker from Boston on cello. Much of it was actually done at Humphrey’s studio, located in the guest house of a former estate in Tuxedo, New York, where new radar technologies were developed in secret during World War II.

With its welcoming yet offbeat eddies of piano, acoustic guitar, woodwinds, and horns, Heavy Metal was a far cry from Geese’s livewire rock. It was also not, Humphrey thinks, the “traditional singer-songwriter” material Winter’s label was expecting. Winter has been open about just how negative the reactions to Heavy Metal were after he turned it in. He’s previously confirmed that a quote in an early press statement — “I’m young and not afraid of living with my parents” — was a shot back at the label higher-up who told him Heavy Metal was not “the album to get you out of your parents’ house.”

Humphrey backs up Winter’s account: “What he says is true, and probably tenfold. It was really gnarly.”

Putnam, for his part, now calls Heavy Metal “another evolutionary step” for Winter, adding: “He had stepped out on a limb creatively, which can be a vulnerable place to be, and when he began sharing the music with people in his close orbit, he was feeling it from all sides.”

The Partisan president acknowledges that, as ever at a record label, the album was discussed in those knotty terms of art and commerce. And he sounds contrite about a loose comment that may have gotten caught in that tangle.

“When Cameron and I spoke about Heavy Metal after he turned in the final masters, I made the joke that strictly on a commercial level, I wasn’t sure if it would be the album to get him out of living at his parents house,” Putnam writes. “In response, Cameron said, ‘I didn’t make this record thinking about its commerciality. People want the real shit.’ He’s now living in his new apartment. Cameron was right, people want the real shit. As he does with all his music, he poured himself into the record, put himself out there, and eight months later sold out Carnegie Hall. It has been nothing short of incredible to see the response.”

Throughout the whole experience, Winter says his bandmates were “always supportive. That was very important.” As Bassin says of Heavy Metal, “I think it scratched an itch that’s always been there.”

Still, the first few weeks after that album’s release in early December 2024, as Geese prepared to head to L.A., “were not good,” Winter says. “It was the Christmas season, no one gave a fuck. There were no reviews coming out. It was all a pretty big disappointment, honestly. I was going into the Geese sessions like, ‘OK, at least now I have a chance to correct things and run as far as I can in the other direction.’”

Soon, though, reviews started to come in for Heavy Metal — and they were largely glowing. Blume remembers seeing the band celebrate together: “They’d all be in a huddle like, ‘Let’s fucking go!’ There’s so much love between them.”

Since its release, most of the songs on Heavy Metal have garnered well over a million streams each on Spotify, and Winter has sold out numerous solo shows, including the aforementioned gig at Carnegie Hall, which will take place in December. It became such a word-of-mouth hit that, by the end of the Getting Killed sessions, Blume says, certain people in the industry started reaching out to him. “I could tell it wasn’t just because they missed me,” he says with a laugh. “I don’t mean like friends or peers that I respect — I mean big executives, and them being like, ‘We want to come hear Geese.’ And I’m like, dope! Everything seemed to change while the record was being made.”

WHEN THEY WERE MAKING Heavy Metal, Humphrey says, he and Winter were keen to make it “sound really haphazard, like a bunch of people playing live in a room,” even if it was often just the two of them. “We felt like something special would happen just off the idea of trying to do something that it could never possibly be,” he adds.

For Getting Killed, there actually were a bunch of people in the room, and they made the most of it. “A lot of the parts were made through 30-minute jams,” DiGesu says.

Winter, who has taken up more guitar work since the departure of former member Foster Hudson at the end of 2023, liked the off-kilter instrumental balance they ended up with on this album. Because Green is so “on the mark” as a guitar player, he half-jokes, that gives him “a lot of license to be really unprofessional.”

Winter isn’t interested in talking about what he brought from Heavy Metal to Getting Killed, saying only, “It gave me ideas.”

Luckily, Bassin and Green are willing to elaborate. The solo record helped Winter figure out what did and didn’t work in the studio, says the drummer. It made him a better singer, adds the guitarist.

“Yeah it did,” Winter acknowledges. “Well, you know, a great many people may disagree.”

Winter has one of those voices on which opinions hinge. It’s fantastically mutable, resonant and weathered, wizened and playful, capable of drifting through soft falsetto clouds or running ragged through the gravel. It has a raw power all its own, but Humphrey also notes Winter’s ability to do something “really contrived” with his voice that still sounds “more emotive in the long run.” Like on Getting Killed‘s closing track, “Long Island City Here I Come,” when he turns a howl into a sneer into a lament over just two lines: “He said, ‘Hang me from a yo-yo/Or a rope, and I’ll be hanging by my neck all the same.’”

Nailing performances like this was an all-consuming process of trial-and-error. Winter says he’ll either get a vocal right on “take one, take two, or take 47.” Humphrey distills the process of making Heavy Metal down to Winter “singing it 1,000 times to get to the guy that ended up singing the final cuts. He had to wear himself down to the point where the person singing was that burnt-out.”

Right now, Winter still records most of his vocals in his childhood bedroom at his parents’ house in Brooklyn. For work so demanding, is there a particular comfort that space encourages, I ask?

“There’s a particular convenience,” Winter says, laughing. “My parents don’t mind me screaming.”

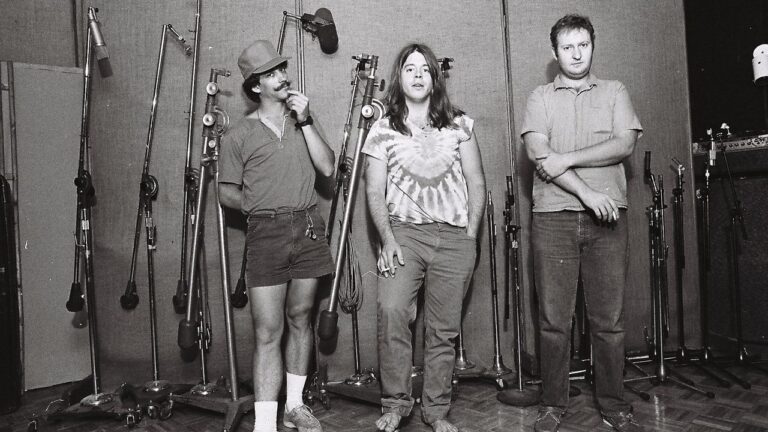

From left: DiGesu, Bassin (on ground), Winter, Green.

Griffin Lotz for Rolling Stone

WHEN I NEXT SEE Geese, they’re ordering sandwiches, PBRs, and their drink of choice, Shirley Temples, at a Brooklyn dive bar, agog at the number of streaming playlists that have added their latest single, “Trinidad.” “This has not happened in the past,” DiGesu says.

It’s a nice boon after a rough weekend of shows. Their Newport Folk Festival set was cut short after three songs because of bad weather. (Or, if you prefer a rock & roll conspiracy that is almost definitely fictional: “Jeff Tweedy took an axe and tried to cut our sound,” Winter cracks.) They then flew to Virginia to play another festival. It was scorching hot, and their set did not go over well.

“I think we got mistaken for a band with a similar name,” Winter says, diplomatically. “It was this sort of jam festival.”

In a few weeks, Geese will return to Los Angeles for more sessions with Blume. Whether this is for a deluxe edition of Getting Killed or a whole new album, they won’t say. Nor are these new sessions necessarily indicative of a fertile creative period for Geese amid the success of Heavy Metal and the swelling anticipation for Getting Killed.

“More like we’re taking corrective measures after the first pass,” Winter says.

“We’ll kill it dead for sure this time,” Green adds.

“Every time we’ve finished an album in the past, we get a call that’s like, ‘Re-do the album,’” Winter continues. “We have to fight really hard not to re-do it. But this time, everyone was like, ‘It’s fantastic! Put it out!’ So we were kind of suspicious. Like, man, we really fell off. We used to be cool, now we’re just making product.”

When Blume recalls his first meeting with Geese last fall — backstage at ACL Fest in a green room filled with bong smoke — the producer posits one comment that may have helped him convince the band to work with him: “I’ve been really horny for mistakes.”

Winter deadpans that Blume could’ve just said, “Leave the imperfections in,” but acknowledges, “The sentiment was appreciated.”

Mistakes do abound on Getting Killed, from cacophonous guitar skronks to stumble-drunk hi-hat taps that completely throw off a song’s rhythm. Geese wanted their songs to “feel unpredictable,” as Bassin says. But getting there involved painstaking perfectionism and frequent 16-hour days. It wasn’t until two weeks into recording that Blume even felt like Geese were enjoying themselves.

“I’m just worried if the songs are good enough,” Blume remembers Winter telling him one night, the frontman’s six-foot-three-inch frame splayed out on a couch in the control room, too exhausted to move.

Even after the band left L.A., the work didn’t stop. One day, Blume says he called Winter to check in and the frontman told him he’d just gotten out of the hospital after a panic attack.

“I was like, ‘Brother, you gotta get a break,’” Blume says. “But that man did not take one break until it was mastered. And then he was sending master notes for four days.”

When I ask Winter if he wants to speak more on this, he declines, choosing to say only, “Eat your vegetables. Take your multivitamins.”

Bassin, there to back up his friend, adds: “Those Flintstones gummies are good for you. But don’t take too many.”

ONE OF THE MOST passionate discussions Geese have in my presence begins as I’m preparing to leave after our second interview. Winter is checking his phone when he suddenly exclaims, “They’re building a new train!” Consummate city kids, the rest of the band listen, rapt and hype, as he describes the Interborough Express, a planned light rail that will connect the outer edges of Brooklyn and Queens by the early 2030s.

The other most passionate discussion Geese have in my presence is one I cannot repeat. Sitting in the bar’s backyard, afternoon sun high, condensation pouring off those Shirley Temples, a joint going back and forth between Bassin and DiGesu, Winter begins to share an idea he’s had for a new live rig for his guitar.

“Cut this out, cut this out,” he says. “I don’t want anyone stealing this.”

The specifics were too nerdy for me to follow, anyway. As Winter expounds, Green, DiGesu, and Bassin listen intently, responding with whoa’s, holy shit’s, and additional ideas of their own. I tell them this is maybe the most animated I’ve seen them all afternoon.

“Well, it’s the fun part,” Winter says with a laugh.

“If I didn’t enjoy that stuff, then it would just be miserable,” Green adds. “I might just be miserable the whole time.”

Geese have been playing music together for nearly 10 years now. They know how to navigate disagreements and spend two months in a van together. They’ve also spread out over the city. DiGesu still resides on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where he grew up; Winter has landed in Bed-Stuy; and Bassin and Green have found homes in Ridgewood, Queens. They see each other at shows, and at practice of course, but the hangs are less frequent than they used to be.

“There’s so many parts in my life that fulfill requirements that can’t be met by these three people,” Green says.

“Exactly,” Bassin adds. “It helps that we remain close, but it certainly feels like a work and play separation.”

This is maybe most revealing in light of Winter’s own breakthrough. There’s no more classic rock & roll story than that of the frontman who goes solo, but Geese seem only to see it as a success for all.

“I don’t think this is one of those fluke situations with the unbelievable frontman and everybody else is cool,” Blume says. “All four of them are fucking genius freaks and I can’t wait for everybody else to figure it out.”