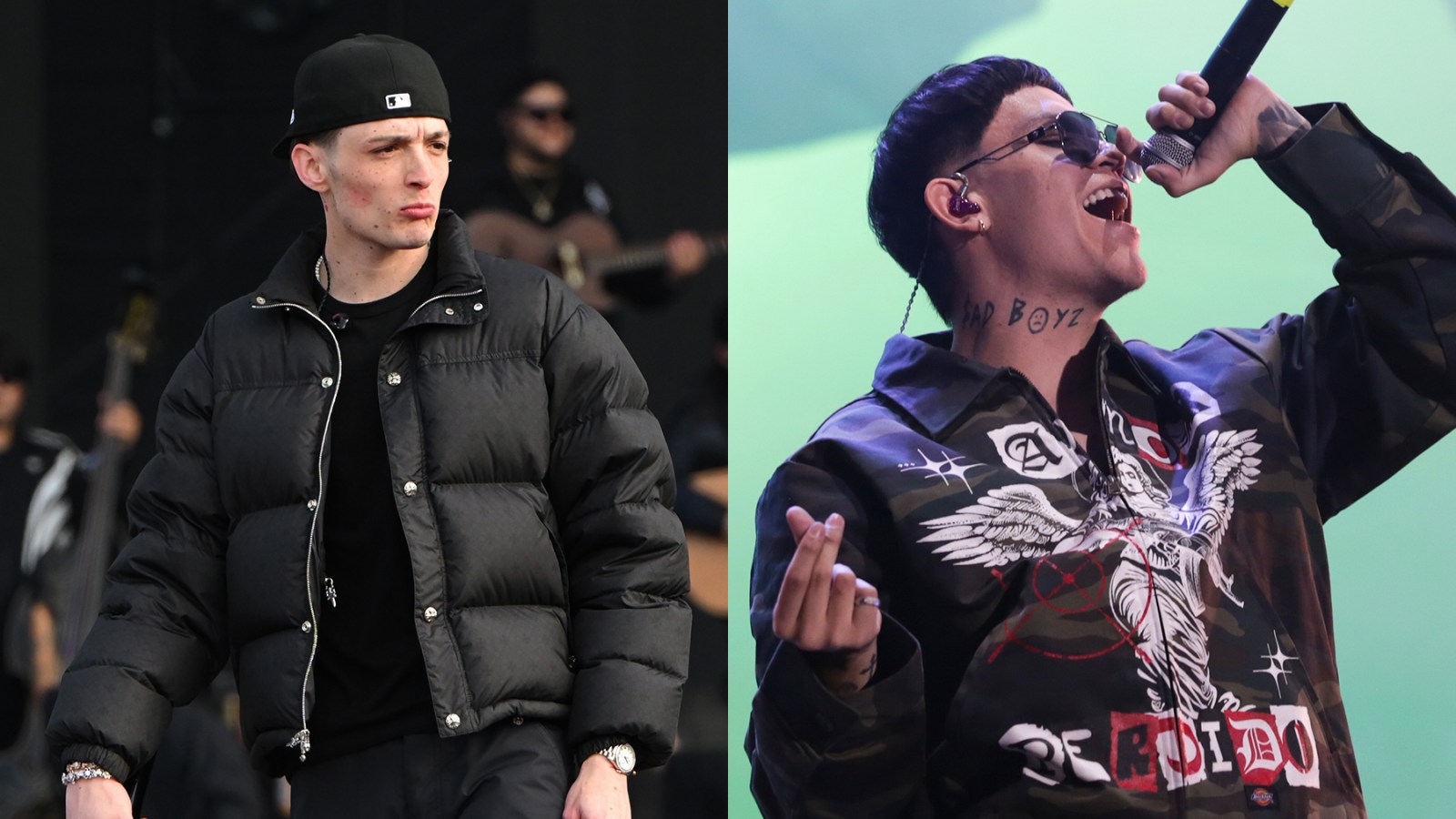

A banner draped from a Tijuana bridge earlier this week carried a chilling warning in bold black letters: “Junior H, refrain from showing up on 08/11. If not, you’re going to get yourself killed.” The threat, currently under investigation by the Baja California authorities, is the latest attempt by one of Mexico’s most dangerous cartels to assert its control over both artists, and the city the banner is placed in.

In recent years, Grupo Firme, Fuerza Regida, and Peso Pluma have received similar warnings from different cartels, prompting them to cancel shows to protect themselves and their fans. A rep for Junior H, however, told Rolling Stone last week that the corridos artist still plans to perform as scheduled.

As música mexicana has surged in popularity, so have “narcomantas” — banners deployed by Mexican cartels to threaten artists and rival groups. In extreme cases usually unrelated to music, these narcomantas have been accompanied by severed heads or dead bodies; other times, they carry simple but serious messages that demand to be taken at face value.

“Narcomantas need to be taken completely seriously,” Mexico City-based criminal defense attorney Ilan Katz Mayo tells Rolling Stone. “The medium is the message. The simple fact that a narcomanta exists sends a message: the situation is dangerous and the threat is real.”

Katz Mayo says that narcomantas are a “way for organized criminal organizations to scare people” and also threaten other cartels or those who work with them. “Sometimes, criminal organizations may have issues with a singer over a lyric or because the artist supports someone who antagonizes that group,” Katz Mayo explains.

In Junior H’s case, the threat — allegedly from the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación — explicitly referenced his narcocorridos: “Not singing narcocorridos now won’t save you. We do not forgive,” it read. The message seemed to point to his past music that alludes to leaders of rival criminal organizations.

Though most of Junior’s music centers on romance and heartbreak, at least two of his songs seem to allude to the Sinaloa Cartel, the group once led by Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, CJNG’s chief rival. In 2022, Junior released “El Hijo Mayor,” seemingly about El Chapo’s late eldest son, in which he sings: “I don’t even need to mention his name / I was the eldest son of that much-talked-about man.” And on his 2023 hit with Peso Pluma, he drops another reference, seemingly invoking “701,” El Chapo’s numerology, adding: “Low profile, the guy, and he’s missed / Though he’s gone, he’s never forgotten.”

“In Junior H’s case, it seems like a personal issue with the artist,” says Katz Mayo. “It’s clear that if someone is offended by something said, the message sent is meant to intimidate the artist.”

But the threats can be deadly serious: While the cartel has not taken responsibility for the killing, Ernesto Barajas, frontman of Enigma Noteño, was gunned down just last month, two years after receiving threats from the CJNG. And in years past, other Mexican artists have died at the hands of the cartel: Corrido legends Chalino Sánchez, murdered in 1992, Valentín Elizalde, killed in 2006, and K-Paz de la Sierra’s Sergio Gomez were targeted by cartels over their musical ties to rival criminal organizations.

With the narcomantas, the intimidation may be a way to assert dominance in a given territory and signal to both artists and rival groups who can assert the most control. According to Katz Mayo, it can also stem from an economic disadvantage: As artists rise in status and begin working with major promoters unwilling to engage with organized crime, local cartels find it difficult to exert their influence.

“Essentially, there are two main motives: one is visceral, and the other is economic,” Katz Mayo says. “A local promoter or regional organizer might pay extortion fees, but large companies like Live Nation cannot do that. They’re unable to operate that way.”

Katz Mayo says that in some areas, concerts are sometimes held in places or areas that are owned or controlled by members of criminal organizations, and have a financial interest in shows played there: whether it’s a venue, the alcohol sold, the security, or simply the area where the concert is being held.

“As artists grow, there are fewer opportunities for criminal organizations to profit because international managers are now involved,” he explains. “The more important the artist and the better their promoters, the more resistance you’ll see from these groups.”

A rep for Junior H declined to comment for this story.