O

n April 26, 1973, a young writer got his first article published in Rolling Stone. “It’s been four years since Poco played their first gig at the Troubadour and everybody made a point of saying the band would be The Next Big Thing,” he wrote. “Five albums and many tours later, Poco is still on the verge.”

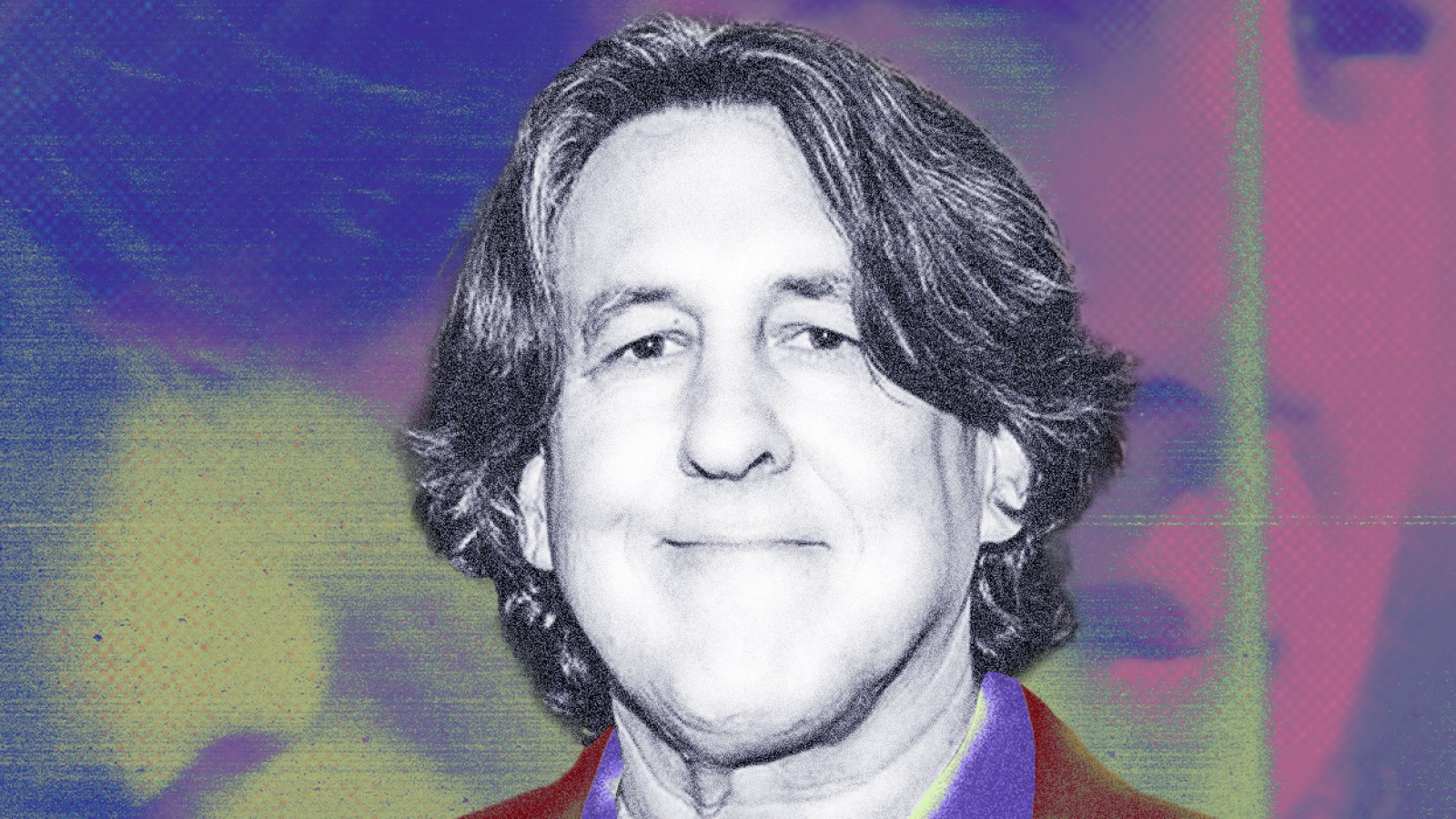

Despite a few hits in the late Seventies, Poco did not become The Next Big Thing. But the article launched the career of Cameron Crowe, who was just 15 years old at the time. Before long, he was writing cover stories for the magazine, hanging with David Bowie on the Sunset Strip, flying cross-country with Led Zeppelin, and going fishing with Lynyrd Skynyrd.

A fictionalized account of his years as a rock journalist resulted in the beloved 2000 film Almost Famous, but more than 50 years after his debut as a professional writer, Crowe is finally ready to tell the real story. The writer-director’s memoir, The Uncool, arrives on Oct. 28. The book is not a salacious celebrity memoir, but a tender chronicling of his Rolling Stone years, where he earned the trust of musicians and witnessed now-iconic concert moments. He also goes deep on his upbringing and family life, and the time he may or may not have prank-called Lucille Ball.

Ahead of the release, Crowe, 68, opened up on all this and more for Rolling Stone‘s Last Word feature.

Have you always wanted to write a memoir?

No. This is really just pivoting back to a kind of writing that I loved. Sometimes you just feel like there’s a sweet spot, and you love living there. Around the time of the [Almost Famous] musical, I felt like I had a lot that needed to get out — that I just wanted to write for me. It was such a joyful experience, and it became 800 pages. It was that kind of writing.

How did it come about?

Ultimately, it also came time to do a collection book of all the journalism that I’d done for Rolling Stone and other places in the day, because I’d gone back and re-interviewed a lot of those people again. And that was my little long-term project. But it turned out that this [memoir] was a good kind of first chapter to all of that. It’s about finding your voice. One person that you meet, interviewing them for the magazine introduces you to another person, and that chain link fence becomes your life and your dream. The book is really about that.

Is that other book still coming out?

Yeah, that’s the next stage. It comes out next year.

You saved everything from your past, from backstage passes to a doodle David Bowie drew you. It must have made writing easier.

I kept everything, because why not? They’re souvenirs from a front row seat. My dream was always, if I get a front row seat, I want to put you in the seat next to me. It’s like, “Here’s what it is to really be in the middle of all of it, and to do diary pieces from within that hurricane.”

The idea, Angie, is to just write a letter to a friend. Don’t write for the world, don’t write to be a writer with a capital W. It’s kind of like when people write about Bob Dylan, they feel the need to swing in the arena with Bob Dylan. It’s like, “No, don’t do that. Get out of the way.” [I wanted to] write this in a way so that it feels like somebody is talking to just one person. It’s you and them late at night and you’re just saying, “Here’s what it was like, can you believe it?” That’s the tone that I love the most.

How long did it take to complete? When we spoke in 2020, you were already working on it.

I kept adding and adding and adding to it, realizing, “You know what? Jerry Garcia was really an amazing interview.” I was a little guy living in San Francisco, and I’m back here now. I’m going to go back into the book and add the stuff about Jerry Garcia, because that was really pivotal for me in a certain way. It was fun to keep introducing people to what’s behind the Wikipedia page on some of your favorite artists. Because over time, you get reduced to whatever that Wikipedia page is.

I just kept thinking, it isn’t a celebrity memoir: “Here are all of the secrets I’ve had in my back pocket to finally tell!” It was a little bit like, “You should meet the David Bowie that I got to meet. You should meet the guy that was giving me a ride home at 6:30 in the morning from the Station to Station sessions, going, [British accent] ‘Do I turn left or right here at this street to drop you off, you who has no driver’s license?’” That guy was a really generous human being that wanted to help my writing voice, by just throwing stuff at me from his life. That was a growth step that you could never have imagined, and resonates constantly with me. So that was an important part of the book to write about.

The memoir ends in the early Eighties, right when your film career is starting. Why did you decide to cap it there?

That was when a new door opened — the door to making movies and taking a step into this really unknown world. That, to me, feels like a whole other life happened. But everything I’ve done has a very obvious road to music.

Tom Petty was responsible for that door opening, while you were conducting interviews for the 1983 doc Heartbreakers Beach Party.

He says, “Pick up the camera and film this.” I’m like, “There’s no director around.” [He said] “Pick up the camera!” And he does this song, ‘I’m Stupid,’ right into the camera. I’m like, “This is amazing. This feeling doesn’t happen when you’re transcribing 12 hours of interviews in the middle of the night. This is going right to the center of the creative process.” Cut. He goes, “Congratulations, you’re a director.”

Each chapter here is like a snapshot of profile subjects.

Yeah. It’s kind of like, let them be singles that amount to an album. I’ve always loved the books that you could carry with you in a backpack and just pull out at any given point when you have 20 minutes, and flip through it and get a feeling. You just want to keep them close. They’re not huge coffee table books or anything. They’re always kind of like Patti Smith’s book [2010’s Just Kids]. It travels well. You really feel like you got a friend in that book. That’s what I was going for.

You also tell your family history here. I imagine that was therapeutic in a way, since most people only know the fictionalized version of your family in Almost Famous.

Yeah. There was a happy/sad quality about growing up in the desert in Palm Springs, and later in San Diego, where music really suited that. I hadn’t written about Southern California at that time ever before. It’s such a vivid memory, and that’s a part of what I love about music. It’s one of those places that you go to in your heart and your mind. It’s like Joni’s song, “My Secret Place.” To write about that world was really satisfying.

We all know about your mom, Alice, and your sister, Cindy, who were portrayed in the film. Did you ever think to include your father, or your late sister, Cathy, in the movie?

No. My oldest sister has always been there on my shoulder. She’s been such a huge presence, and she’s been gone for a long time. Obviously when you’re 10 years old and you lose a sibling who’s 19, it’s like, “Well, they were an adult.” So I always thought of her as an adult. And then you get older and you realize she was a teenager. She never got out of her teens. She was living in that world and she loved Brian Wilson. Brian Wilson was that nearest faraway place and she gave that to me. Over time, I realized how much I owe her, and my sister Cindy. The book’s a lot for them.

Cathy was a huge Beach Boys fan. Knowing that now, I view that “Feel Flows” scene in Almost Famous differently.

I had heard a story from someone who had gone to see Almost Famous in the theater, and when the movie was over and the lights came up, there was somebody crying behind him. And my friend turned around and it was Brian Wilson. He said, “Hey Brian, why are you crying?” He goes, “Because that’s my brother. That was my brother singing that song.” And that to me was like, “Walk away.” If this film burns in a lightning blast five minutes from now, I’m good. Those are the little victories along the way, where the music person inside of you was like, “Yes.”

The book begins in 2019, when you’re at rehearsals for the Almost Famous musical. You’re on the phone with your mom, and you scream, “I want my old life back!” What did you mean by that?

When I was directing and doing everything myself, and looking forward rather than potentially looking backward. And the richness that could be mined from looking backwards in a format that I didn’t know, which was musical theater. So it was kind of that cry for help that was supposed to happen unheard by anyone else, but one of the crew was just a few feet away smoking a cigarette and heard everything. So I wanted to write about that in the book, too. The act of looking back is very dangerous.

You write that you didn’t see a lot of rock & roll excess at first. At what point did you witness it?

Being backstage interviewing Steve Marriott from Humble Pie. I come from a school teacher mother. Drugs are the enemy. He has a green Heineken in his hand and he’s in the locker room of the San Diego Sports Arena, and the conversation’s going really well. And then from his other hand comes the biggest hash joint I could have ever imagined. It was out of a Robert Crumb cartoon. It was so huge, and I was like, “What do I do if he offers it to me?” And he did, and I was like, “No thanks. Not today.” He’s like, “Smart, more for me.” And I heard that forever, since that day.

If you don’t do the drugs that you see, you’re not there to party with them, and you send that message, which is cool. The huge excess was kept from me a lot, though I saw the hint of some of it around the edges. Sometimes, you can say a lot in between the lines. Grover Lewis did that big profile of the Allman Brothers Band [in 1971] before I did mine, and he just went right into a kind of procedural explanation of the drugs everybody was doing. I didn’t want to do that, because that felt like a police report.

It’s a case-by-case basis. Some [musicians] are like, “Yeah, write about anything!” or you sense that about them, and you do. Other people you feel like, “I just want to write about the creative process, and I’m not interested in partying with you until two a.m., so I’ll leave at midnight.”

You did indulge sometimes, though. You write that you had a Pimm’s cup with Ron Wood, and planted some seeds from Bob Marley’s weed in your backyard.

[Laughs.] Thanks. There was a siesta hour from time to time, but mostly, you’re never going to get the story done or delivered in time if you’re that guy who is there for a dual purpose. And I think there’s a kind of journalist that gets filtered out of the process pretty quickly if you realize that they’re there to make friends more than write something from the heart.

This is a good time to talk about your baby face. You write that you were kicked out of clubs for being underage, but it also made musicians trust you. I see it as a blessing and a curse.

I grew some facial hair in the early Nineties when I was living in Seattle, and that was really a mistake. People that saw that were like, “No, no, no, no, that look is not you. Just stop that, here’s this razor, go get rid of that.”

In 1975, you got a Rolling Stone assignment that was a bit different from your usual beat. It was an essay titled “How I Learned About Sex.”

I ended up putting this in the book at the last minute, too. Tim Cahill was an editor that worked with me a little bit on the Allman Brothers story. He called me up and said, “I want you to do something that’s not about music.” I’m like, “Sounds great!” And he said, “It’s the men’s issue.” And I’m like, “Fantastic!” And he goes, “The subject is how you learned about sex.” And I’m like, “Gr—great!” And then proceeded to die on the vine trying to write this story. At the last minute, I just spewed out a lot of the embarrassing stuff that I never wanted to tell anybody, and sent it in.

The call was instantaneous. He was like, “This is what you should be doing. This is real writing. I laughed my ass off. Wow, this is embarrassing.” The embarrassing stuff is what people always love. Be personal, but don’t overtake the story, was the lesson I took from that at.

You wrote cover stories on Led Zeppelin and Joni Mitchell — musicians who weren’t exactly fans of Rolling Stone. The former is particularly impressive: you convinced Jimmy Page to do the cover while he was eating a bowl of cereal.

I’m telling you, I’m still shocked it happened. That was a line that was never supposed to be crossed, Led Zeppelin appearing in Rolling Stone. But it was the music fan in him that really helped that happen, because I had a bootleg tape of a Joni Mitchell interview from Canada, and he’s a fan, and he wanted to hear it.

And you never got it back.

I never got it back. I finally got another copy of that interview a couple of weeks ago, so it came home to roost in some way or another.

© Neal Preston*

You got to witness now-legendary songs in concert when they were brand new. Material from Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti, the Who’s Quadrophenia, and Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Simple Man.” Did you have a feeling at the time they’d become classics?

That’s a really good question. It felt classic in the moment. [Photographer] Neal Preston and I would go back to the hotel room and recap at the end of these wonderful nights. You just wanted to take those little moments and treasure them. How much better can it get than Lynyrd Skynyrd at Winterland with Ronnie Van Zandt barefoot? We had that feeling a lot: “If it’s this good now, how good is it going to be? This is one of the best rock shows ever.” And it was. That thing — that white-hot moment for rock — was never the same in that way again.

You went fishing with Van Zandt in Hawaii. Was he any good?

None of us caught anything, but he was a really good fisherman. He reminded me of Duane Allman on the cover of one of those archives albums, where you’ve never seen a guy more comfortable holding a fishing rod. This is what this guy is meant to hold in life. And most importantly, he knew how to have fun catching not one bite. It was just a wonderful afternoon.

Mistakenly, I’d recorded a little bit of that, and heard it back in the context of a mixtape that I didn’t even realize had them recorded on it. This was some time ago, but I was in the kitchen listening to this mixtape. It was like, Paul McCartney and Wings’ “Beware My Love.” And there was Ronnie and the guys from Lynyrd Skynyrd from years earlier fishing, laughing, talking about music, and it all came back. And then with a click, it went back into “Beware My Love.” And I was just like, “Fuck, man.” And I’ve not let it in because I have been so sad since Ronnie died, but I started listening to Skynyrd again after that.

You also interviewed Gram Parsons and Jim Croce, who both died a day apart, in Sept. 1973.

You tend to really be imprinted by the first people that you knew who died in your life. They took the time to really bond. Jim Croce even more than Gram Parsons, but you have this indelible time where they reveal part of themselves to you and trust you. That was so vivid to be 15 and have Jim Croce say, “This guy is here to interview us!” And I was just sitting in the wrong dressing room. But the guy ended up just telling stories, and I ditched school the next day and there were more stories. I just felt like, “I’m meeting people that get me as opposed to some of the people at school.” And then he died, and Gram was gone in an odd, mystical way. So there was a feeling at the time of, “Grab this time around your heroes, because there’s a danger and sometimes there’s a body count in this business of people in their little planes.” I was always scared of little planes.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever gotten?

Act like you belong until you do belong.

What about from the Eagles’ Glenn Frey? I know he loved to pass down his wisdom to you.

Oh, man. I put that into a scene in Fast Times at Ridgemont High. It’s spoken over a cardboard cutout of Debbie Harry, which is like, “If they can’t smell your qualifications, move on.” I felt like Debbie Harry when Glenn was telling me this. He was such a student of how to slip into a room and make everybody part of your sport, which is, “Let’s all do great stuff together.” That was the sport of Glenn Frey. And along the way, if somebody tries to hold you back, move on. Don’t let it get you down. If they can’t smell your qualifications, fuck them.

You once left your wallet in the bathroom at CBGB’s, and Dee Dee Ramone helped himself to $75. Did you ever tell him you knew he stole it?

No, I did not. I don’t think people would really imagine that I would’ve been around the Ramones when the Ramones were first starting. It’s kind of like, “What happened? Why didn’t he stick with the Ramones?” But I was moving back to California, and I think it was a little bit like I was leaving their wonderful land, their wonderful kingdom, never to return, when I was moving to California again. But being around them at that pivotal time was amazing. I felt sad that he had to steal some money from me, but I knew that if people were able to appreciate how unique the Ramones were, that things would be okay, at least for a while.

You also had an unpleasant encounter with Lou Reed while in New York.

And apparently it continued throughout his entire life, because I spoke to somebody who was friends with him, and I was like, “Yeah, I always wondered what he thought of Almost Famous, when Philip Seymour Hoffman and Patrick Fugit debate the relevance of Lou Reed and his association with David Bowie.” And the person I was talking to said, “Oh, let me end the mystery. He didn’t like it and he wasn’t a fan of yours either.” I’m sorry to Lou Reed [Laughs.] It didn’t go his way in that scene.

What advice do you wish you could give your younger self?

Keep everything. Because one day you’ll be able to look at this souvenir that means so much to you, whether it’s a tape of somebody talking or something somebody gave you, and it will all come back and you will have this moment again.

© Neal Preston*

Do you ever regret jumping straight into adulthood as a teenager and missing out on that period of your life?

I do. I miss some of those things. Some of the things I’ve been able to go back and check the box on. That’s a thing that I’d always had as a conversation with my sister, Cindy, because she had a message for me, which is, “Take time to be an adolescent.” Take time to live the life of the people that are in those audiences while you’re lucky enough to be in those crowds. Did you ever want to have fun like them as opposed to having to run home and transcribe and have a story done within days? Will you miss one day, the other life?

So yes and no. When I really think about it, I wouldn’t trade the life that I was able to have in those years, and I was very happy to write the book and share the highs and lows of that whole period. So I think some people think like, “You had a charmed life, you got to do all that, and you were doing stories when you were young.” It’s like, “No, there were a lot of hills and valleys.” But it was worth it because you should do the thing that you can’t say no to, and that was writing about music, particularly in that time.

You were briefly in a high school band, the Masked Hamster. Do you ever think about what would have happened had you not gotten kicked out, or was it just a hobby?

[Laughs] Do you know how amazing it is to be asked that question? The Masked Hamster is actually a band we can talk about. Maybe that was my dream. I don’t know, man. If I had been able to play “I Can’t Explain” properly with a band, I may have never written another word. I was so happy in that moment, but I guess I just summoned that pleasure in another way, because I was really not meant to be a musician.

What about if you’d stayed writing for Rolling Stone, and hadn’t moved onto directing? Do you ever think about what would’ve happened?

I do a lot, because [film] barely happened. Fast Times was definitely put on the most back of back burners by the studio, and it really was like a death march to the movie being released. So those dreams did not exist. When people started showing up in Spicoli Vans, it was like, “What? This is a miracle.” But I would’ve kept on writing. I think I would’ve written stories like Ray Bradbury, because he had wit and soul to him, which was the stuff that I always loved. When there was a little meat on the bone, but it was also fun. Ray Bradbury would’ve been my guiding light.

The media landscape is drastically different now than it was in 1972.

Journalists are being laid off hugely all the time, and it’s tragic. So that’s a reason to wave the flag for journalism. You are a journalistic hero. You’re out there doing stuff at a time when it’s hard to spend a couple thousand words writing about Judee Sill. So there is a nobility to that, but it’s also just like being a journalist has been trivialized as a job. They’ve been the butt of jokes lately, and it’s ridiculous. If this book does anything, I would really love for it to get across the joy of what it is to be a journalist when things are really cooking and you are there exploring something that’s near and dear to your heart, and you can write about it, that is a hugely important thing.

It’s tougher now than it was, but it’s more immediate, which is great. You can immediately find out about last night’s show with Neil Young. You can immediately find out how the set lists are changing. So media is really wonderful that way.

Do you think that social media has robbed rock stars of their mystique?

Absolutely. There’s so many outlets and a million podcasts. To find an artist who shrouds themselves in just a little bit of mystery is a beautiful thing, but it’s so hard for them to drop an album. There has to be a campaign. And once you’re campaigning, you’ve lost mystique. So the ball game is to keep people interested in that magic thing that happens when you capture a feeling, and not talk about it and dissect it and sell it so much that it loses its power. So this is the daily battle that we wage.

What’s the best and worst part about success?

The best part of success is that people can know that you have a voice and you can meet with an actor that you’re interested in working with or call and ask for access to an artist that you know or appreciate or want to write about, and they might know your work. That’s the best part.

The hardest part about success is … I don’t know, it all feels like a gift. When I was first starting to write, James L. Brooks told me, “Buddy, think of the privilege we have. We got the greatest job in the world. We get to tell stories.” And I still feel that every day.

What did you learn from the Almost Famous musical?

In San Diego, it was a smaller, heartfelt thing. It ended up being something that was completed by my mom dying, which I’d never thought would happen. The emotion of her dying just bled through the cast. They took the baton of everything that had happened, and did it for my mom. And then Covid happened, and it was rolling the boulder back up a very bigger hill. And I think we learned, once again, what we already knew, which is the most personal and passionate version of the show is the show to do. There’s going to be a performance of it in Connecticut in October. So we did some more work on it, just to use what we learned from the Broadway experience. It’s a living, growing thing, and I learned a lot.

I’m sure the negative reviews were hard to swallow.

Yeah. I just will always remember Casey Likes the day after, when a lot of the reviews had hit. Here comes the kid who’s playing you as a young guy, an optimistic young warrior. Here he is leaping down the street, literally jumping, saying, “This just makes me want to do better and better and better!” It was an amazing moment that I’ll never forget. These things all take time. Scripts take time and plays take time, and bands take time and songs take time. It’s the beautiful journey.

The memoir is a great way to introduce younger audiences to your writing, who are mostly familiar with you as a director.

Yeah. Led by this thing that I did grow up with, which is, “Put on your magic shoes.” Everybody always says “you can do anything” to a young person growing up. I actually believed it. There was only one person in the whole time at Rolling Stone that ever said, “You’re too young to be able to write about me.” Everybody else was like, “Okay, sit down. What else you got?”

Who was that?

Steve Miller.

What music still moves you the most?

Maggie Rogers. My Morning Jacket. That’s who I’ve been listening to a whole lot right now. That and a lot of Joni Mitchell, but that’s another story entirely.

What has raising a child at this stage in your life taught you?

My whole life, I’ve heard what it’s like to be a girl dad, and I was lucky enough to have twins, two boys. So now to be the father of a little girl and seeing exactly what people have been telling me my whole life, that it is different and extremely entertaining. And what can I say? She’s heard her first Jackson 5 record, Dancing Machine, and she dances. It’s a gift that I wasn’t expecting, and now can’t imagine being without her.