D

’Angelo and Questlove were sitting on a couch in a swanky hotel watching, or rather, microscoping a video of James Brown performing in 1964. D and Quest observed every gesture, each dance step and light cue, and anytime the Godfather of Soul subtly signaled the band to do something.

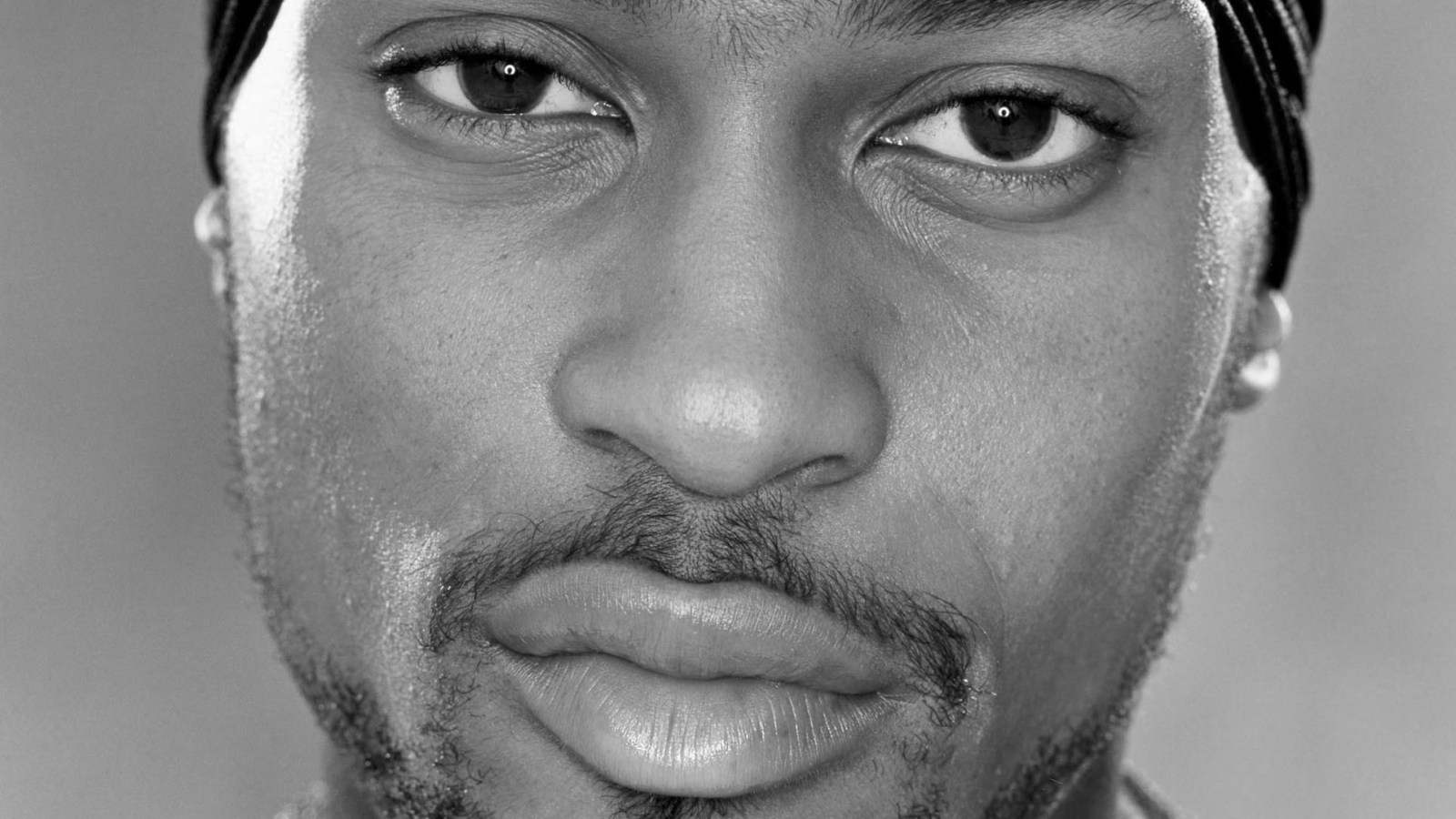

This scene transpired 25 years ago. I was in the room covering D’Angelo for Rolling Stone. He was, at that moment, one of the hottest artists in the world. His sophomore album, Voodoo, had established him as an undeniable musical genius. It was the zenith of the modern soul genre — deep, powerful, sexual, sensual, and intimate. It was precisely what drew so many to soul music: an album of long, dirty grooves, falsetto serenades, and gut-tickling bass. And it wasn’t just music, it was D’s declaration of war over the future of music.

D’Angelo told me this is how he saw it: Music was becoming overly commercial, and Voodoo was an attempt to push artists away from that towards following the voice inside — wherever it led. Voodoo was also meant to get Prince’s attention, with the hope of convincing the Purple One to collaborate with D and Quest on an album — essentially, to serve as an audition for Prince — but that’s another story.

D was on top of the world — a bonafide superstar musician — and even still he was sitting there studying the greats like a hopeful student. Not just Brown, but also Stevie Wonder, Prince, Al Green, Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye — the soul music canon, in a sense. They called these predecessors “Yodas,” and the videos were called “treats.” That day Questlove said to D, “What would your life be like if you hadn’t seen that George Clinton treat?” D answered: “Totally different.”

Watching him hyper-analyze older musicians helped me understand some of where D’s greatness came from. He was a serious student of his craft, and a hard worker, even though he was amazingly gifted. In fact, he was so naturally talented from such an early age that his older brother told me they never thought D would be anything but a musician.

D grew up playing in a pentecostalist church in Virginia and went to New York City in search of a record deal as a teenager as part of a trio. The label said, we only want him. His debut album, Brown Sugar, put everyone on notice: there was a new soul giant in town. His single of the same name, a cheeky back-and-forth about his love of marijuana, was among the top songs of that summer in 1995. But some felt it was a project left unfinished, as if the songs were more like sketches. Five years later, D erased all of that with his second album, Voodoo. It was a towering achievement that made it clear that he was not only a disciple of soul legends, he was their peer as well.

But Voodoo led to a problem.

The song “Untitled (How Does It Feel)” was D’Angelo’s masterwork: a swirling groove of erotic funk so hot you could get pregnant just by hearing it. His manager, Dominick Trenier, envisioned a video where D was alone on a stage with the camera giving us closeups of his incredible body — from his cornrows to just below his belly button. It would be simple, and sexual, and powerful. This would be the culmination of years of work on his body. When D dropped Brown Sugar he was overweight. In the five years after, as he worked on Voodooo, he changed his diet and trained obsessively. When it was time to shoot the “Untitled” video, D looked as fit as a human could possibly be. But he didn’t want to do the video. His limo pulled up outside the shoot, and he refused to get out. He was nervous. Trenier came out and sat with him until finally he felt ready.

They went in and created one of the most iconic videos of all time. The video hit the culture like a neutron bomb and titillated everyone. Was this the best-looking man alive? Maybe. The visual alone gave D’Angelo an even bigger profile. But here comes the rub: after “Untitled,” people began to see the singer differently. At his shows, fans screamed for him to take his shirt off. That was acceptable, but he wanted to be seen as a musician.

D had studied music like a graduate student and then spent five years working on Voodoo. He wanted it all to be about songs — to convey that he was a great musician — but they were screaming so loud for his abs that you couldn’t hear the music. He felt like he’d been demoted from genius to sex symbol. He rebelled by disappearing. We spent years missing him. His third and final album, Black Messiah, came out in 2014, more than a decade later.

Voodoo remains a towering achievement. It will be remembered as a powerful source of inspiration for so many, proving he may have persevered in the war he took on so bravely. D’Angelo reminded people that you can be successful by listening to your muse, ignoring industry trends, and giving the people innovative music.

Now, D’Angelo is gone, and when I hear his progeny — artists like Frank Ocean, HER, and SZA — it’s like watching beautiful flowers bloom from the musical seeds he planted. All of which is to say, in the long game, he won.