My book Backbeats: A History of Rock and Roll in 15 Drummers tells a familiar story from an unfamiliar vantage. Moving from Chicago blues to Phil Spector’s early-1960s confections to the British Invasion, the birth of punk, metal, grunge, and hip-hop, the book tracks the seven-decade story of rock and roll as if drummers were the main characters.

And why not? Though they aren’t typically as famous as guitarists and singers, drummers have been just as crucial to the creation of this music, possibly even more so. Rock and roll was a rhythmic revolution above all, and who could imagine what it would look like without the Bo Diddley beat (created by drummer Clifton James), the “Be My Baby” intro (played by Hal Blaine), or the thunderous power of John Bonham?

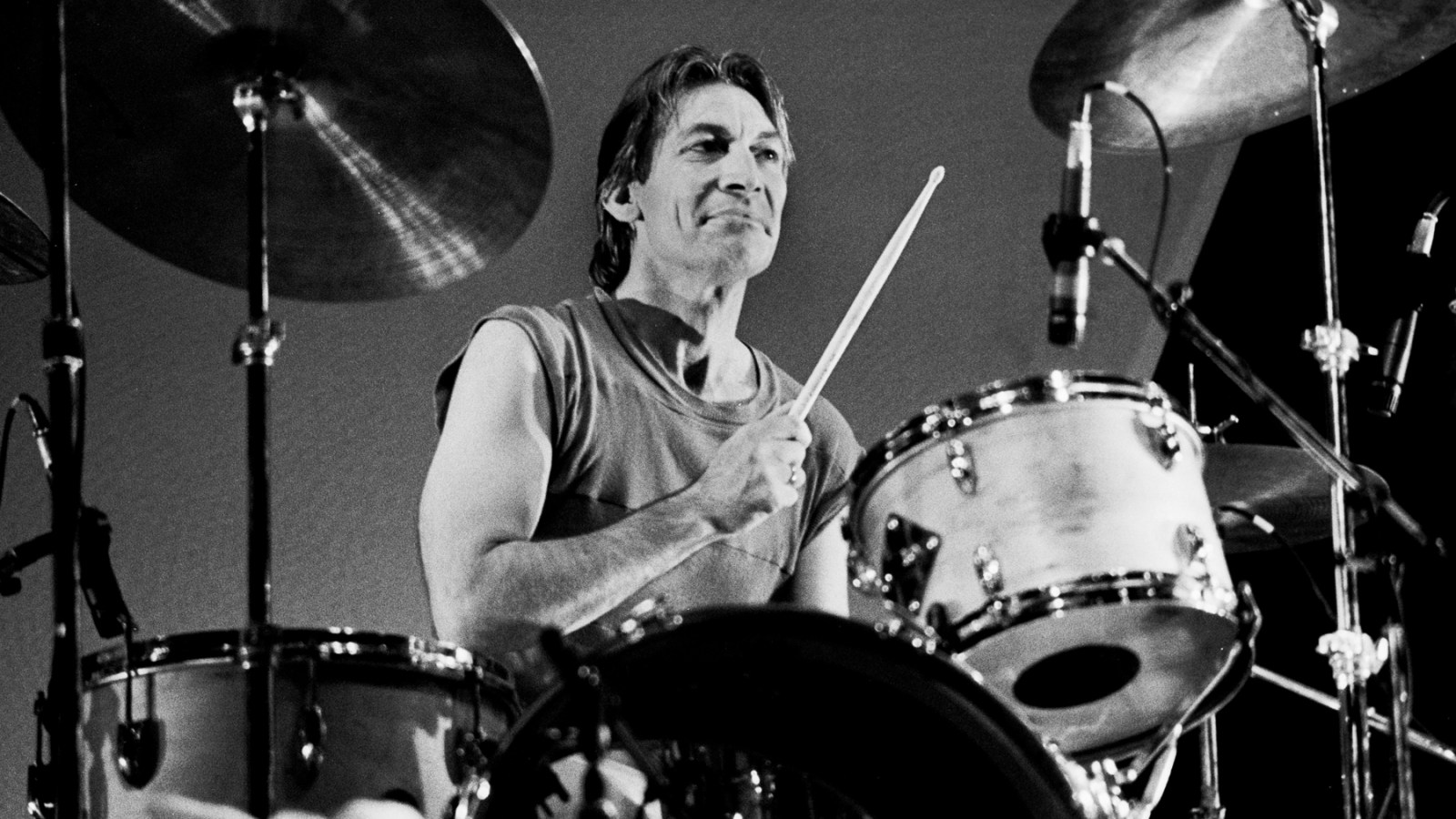

Charlie Watts embodies this book’s thesis. It’s impossible to imagine the Rolling Stones without him, and he was just as crucial to their sound as Keith Richards’ guitar or Mick Jagger’s singing. In this excerpt I discuss why his blues- and jazz-influenced style was so unique and important to their group’s development.

It’s hard to overstate how difficult it was for young British people to obtain records from American jazz- and bluesmen in the 1950s and ’60s. Figures like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Bukka White, and even Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf were still obscure in the US at the time. It wasn’t until 1958 that Waters and a few other performers came to Britain for a tour, and if you missed those concerts then you had to make do with what you could find in the few specialist record shops, where obsessives like Brian Jones and Keith Richards were your competition for the limited supply. Lonnie Donegan, a crucial figure in the development of UK rock and roll, got his early jazz and blues records by stealing them from the American embassy in London. But the scarcity drove these young men together.

“That scene became the only chance you had to play that music,” Charlie Watts said. “It was a chance to talk about those records.” When Keith Richards and Mick Jagger arrived in London’s burgeoning local blues venues, they found Watts already playing drums a few nights a week with another band while attending art school.

The trio of Jagger, Richards, and Watts played their first gig together in 1962, before Beatlemania. From the start, their tastes ran rougher than the pop-minded Liverpudlians: they made their reputation on Wolf and Muddy covers, and the Stones would never have been caught playing tunes from The Music Man, for instance. But in their early years, Jagger and Richards were relatively focused on traditional British songcraft, especially in their ballads. Original songs like “Ruby Tuesday” and “I Am Waiting,” even “Paint It, Black,” revealed eclectic, exotic tastes and studio approaches.

Courtesy of Simon and Schuster

The latter became instantly iconic for its sitar melody, but it is also a major drum feature, especially for the time. Watts’s pounding toms set the tone for the thrumming verses, then he leaps into the chorus with a heavy backbeat and massive fills. And as much as Watts is known for demureness, both musically and otherwise, it’s worth noting that his wild playing is all over the band’s mid-1960s singles and hits, from “19th Nervous Breakdown,” which perfects the Who’s jacked-up R & B feel, to the swinging triplet blues “Heart of Stone,” and the power-pop buried gem “Gotta Get Away.” Then there’s “Get Off of My Cloud,” which opens with Watts’s bouncing beat, built on a snare fill. All these songs rely on a strong backbeat more than harmonies or guitar solos, for example. The drums are intrinsic to the arrangement, even in this more traditionally melodic era.

In the defining early Stones anthem “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” Watts’s drum break—performed only on the snare and hi-hat—is a hook to equal Richards’s three-note guitar melody. The song swings on Watts’s snare drum throughout, as he keeps a steady quarter-note pulse. Instead of a traditional backbeat on the two and four, Watts played every note on “Satisfaction,” one-two-three-four. The Rolling Stones were defined by the sound of Charlie Watts’s snare from their first public breakthrough.

That snare sound is as instantly identifiable as Miles Davis’s muted horn or Eddie Van Halen’s pyrotechnic neck tapping. No one else has a backbeat like Charlie Watts, and it’s the first thing any drummer will say about him. So how did he achieve it? Like any iconic musical voice, he had his physical peculiarities. He played with a “traditional” stick grip, meaning his left stick, which hit the snare, went through his fingers at an angle like a bottom chopstick. Drumming with a traditional grip takes the power away from your elbow or shoulder—they won’t be any help. It has to come from the wrist, in a whip motion, like a viper attack. Charlie Watts held his trunk and head so still, and never played loudly or overexerted himself, but his snare sounds like he was whacking the dust off it, like he’d put in a dollar and never got his cigarettes.

Watts also played a lot of rim shots, where the stick hits the head and the metal hoop around the drum simultaneously. It further sharpens the sound into a crack rather than a thud, and forces additional reverberations from the drum’s shell. Watts’s snare sound was really a mix of sounds—a thwacking snap on the head, the vibration of the air in the drum itself, the click of wood on the rim. Recorded in faux-blues verité style, his backbeats were alive. And like fingerprints, no two were precisely the same.

It shouldn’t surprise any blues fan, but Watts achieved this sound on banged-up vintage equipment, even as the trend for giant, customized sets grew through the 1970s and ’80s—even when he was competing for stage space with Mick Jagger riding on a giant inflatable penis. Gina Schock is the drummer for the Go-Go’s, who opened for the Stones on the Tattoo You tour in 1981. “The drum tech said the rug underneath it was worth more than the kit,” she told me. (She added, in a south Baltimore drawl that she has heroically preserved despite a half century on the West Coast, “Charlie was a perfect gentleman.”)

Moreover, he played his ancient drums quietly. No matter how big the Stones’ crowds got, no matter how enormous the stage show, you’d never see his elbows raise. He played everything at a reasonable, even modest volume, and let microphones capture the nuances of his sound—another jazz technique. If your art depends on developing a unique voice, you don’t seek it by screaming all the time.

I spoke with Steve Albini, the fiercely, iconically independent musician and recording engineer, in February 2024. Known for his unadorned, documentary techniques and specifically for his full-bodied drum sounds, Albini recorded all-time records for the Pixies, Nirvana, Slint, PJ Harvey, Low, and literally hundreds of other bands over three decades, in a schedule that ranged from experimental groups in his actual neighborhood to Robert Plant and Jimmy Page. His artistic philosophy was closer to that of Alan Lomax (or his fellow adopted Chicagoan Leonard Chess) than what we typically think of as a “record producer.” “I like it when a recording is convincingly naturalistic,” he told me. “That’s the most successful basic recording scenario, when it’s a convincing representation of what was happening in the room. The band should be allowed to do whatever the fuck they want to do. I’m here to help.”

I called him to ask about drummers, and he brought up Watts unprompted. “The thing that’s amazing about Charlie Watts is the little rhythmic peculiarities in his playing. It’s almost like his playing is for him alone. He marches right through the song. His natural gait has a loping to it, it’s not boom-boom-boom. There’s a pulse, separate from the tempo, and I love how committed to it he is.”

In the 1970s, Watts started to omit his hi-hat when he played backbeats, which put even more emphasis on the snare. You can hear just how clear it is on “Sway,” “Happy,” “Beast of Burden,” and other masterpieces from this era. “His hi-hat peccadillo, the lift,” Albini described it, “it’s like a hardcore drummer. And it creates a stutter in the rhythm.” He compared Watts to two other masters of rhythmic simplicity, AC/DC’s Phil Rudd and Bun E. Carlos from Cheap Trick, both of whom had such uncluttered styles that their personalities, like Watts’s, shone through in the spaces between their notes. They defined their bands by their unrelenting swing and backbeat. They made themselves elemental to their bands’ personalities.

Those two hard rockers came well after the Stones, however. Tremendous as they both are (and my goodness, I love Cheap Trick at Budokan, a drastically underrated drum album), Watts never hit hard. He emphasized his backbeat by keeping his playing loose; everything in his entire bodily approach to drums was designed to highlight the snare. His fellow drummers, always his sharpest observers, said as much. “Charlie played even less than me,” Ringo once joked. Stewart Copeland of the Police noted that Watts’s jazz influence meant he “derived power from relaxation. Most rock drummers are trying to kill something; they’re chopping wood. Jazz drummers instead tend to be very loose to get that jazz feel, and he had that quality.”

This essay is adapted from John Lingan’s new book, “Backbeats: A History of Rock and Roll in Fifteen Drummers,” which will be published by Scribner on Nov. 11.