Happy 40th birthday to the Clash’s Cut the Crap, the most hated album of the Eighties. History is full of cases where great bands make terrible records, yet history stands speechless at what the Clash accomplished here. Cut the Crap came out in November 1985, and got instantly repudiated by Joe Strummer and anyone else involved with it. It’s the all-time case of a legendary group with a previously impeccable discography who make one flop so mind-blowingly awful it kills off the brand forever. As Strummer said a few years later, “You probably could put it under the flogging-a-dead-horse file.”

Cut the Crap has gotten erased from the Clash’s official history. It’s not listed in the discography or timeline on the band’s official website. It goes unmentioned in the documentary Westway to the World, left out of almost all their reissues and compilations. Never has such a great band gone out with such a humiliating disaster. How did this happen? How did the Only Band That Matters stumble into one of the most infamous rock & roll fiascos?

“It was a complete fuck up,” Joe Strummer told the NME in the summer of 1986, admirably taking the blame. “What you must realize is that a large percentage of people like me are idiots. I sit in a room and write ditties while others are selling stocks to Malaysia on the vodophone. It’s easy to manipulate people like me. What I do best is write doggerel so a part of me must be very childish.”

The Clash were coming off one of history’s all-time great five-album runs. The London punk rebels seized the revolutionary spirit of 1977 with their raw manifesto The Clash, then refined their sound with the flawed Give ‘Em Enough Rope. They peaked with their classic London Calling, the one Rolling Stone proclaimed the best album of the Eighties, but then reached even higher with their sprawling epic Sandinista! They finally broke the U.S. with Combat Rock, with hits like “Rock the Casbah” and “Straight to Hell.” Crucial and influential albums, every one of them. Four horsemen, on top of the world.

But in a shocker move in September 1983, Joe Strummer kicked guitarist Mick Jones out of the band, denouncing his former mate as a rock-star sellout. Since Jones was the guy who wrote the actual songs, this might have been a danger sign. But Strummer and bassist Paul Simonon announced they were going back to basics, hiring a new band of unknown kids: guitarists Nick Sheppard and Vince White, drummer Pete Howard.

And then…well, it’s hard to overstate how bizarre it sounded to drop the needle on Cut the Crap. After replacing Jones, Strummer and manager/producer Bernie Rhodes replaced the band with drum machines and synths. Simonon didn’t play bass at all. The result was a total mess full of failed radical anthems like “Dictator” and “Dirty Punk.” If you listen to Cut the Crap today, you might find it tough to believe this got released, like, for money. Especially “We Are The Clash,” a cartoon theme song with a sing-along choir of robot voices chanting, “We ain’t gonna be treated like trash / We got one thing / We are the Clash!”

To make it worse, Cut the Crap came out almost simultaneously with the debut from Mick Jones’ new band Big Audio Dynamite, infused by hip-hop, with the clever dance-floor hit “E = MC2.” It made Strummer look even more obsolete. The silliness was amplified by the “Clash Communique” on the sleeve, as if delivering a top-secret urgent message. “Wise MEN and street kids together make a GREAT TEAM…but can the old system be BEAT??…no…not without YOUR participation…RADICAL social change begins on the STREET!!…so if you’re looking for some ACTION…CUT THE CRAP and Get OUT There.”

This album was so traumatizing for teenage Clash fanatics like me. Over the years, it’s been tempting for some partisans to claim it doesn’t count as a real Clash album — it was all the manager’s fault. But no, alas, it’s not that simple, because it’s not merely a bad album, but a bad album made out of passionate conviction and devout belief. That’s why Cut the Crap has gone down in history. It’s not just another lousy Eighties rock-star fiasco. It’s the kind of bad album that can only happen when true believers get all the wrong ideas and pursue them with absolute dedication.

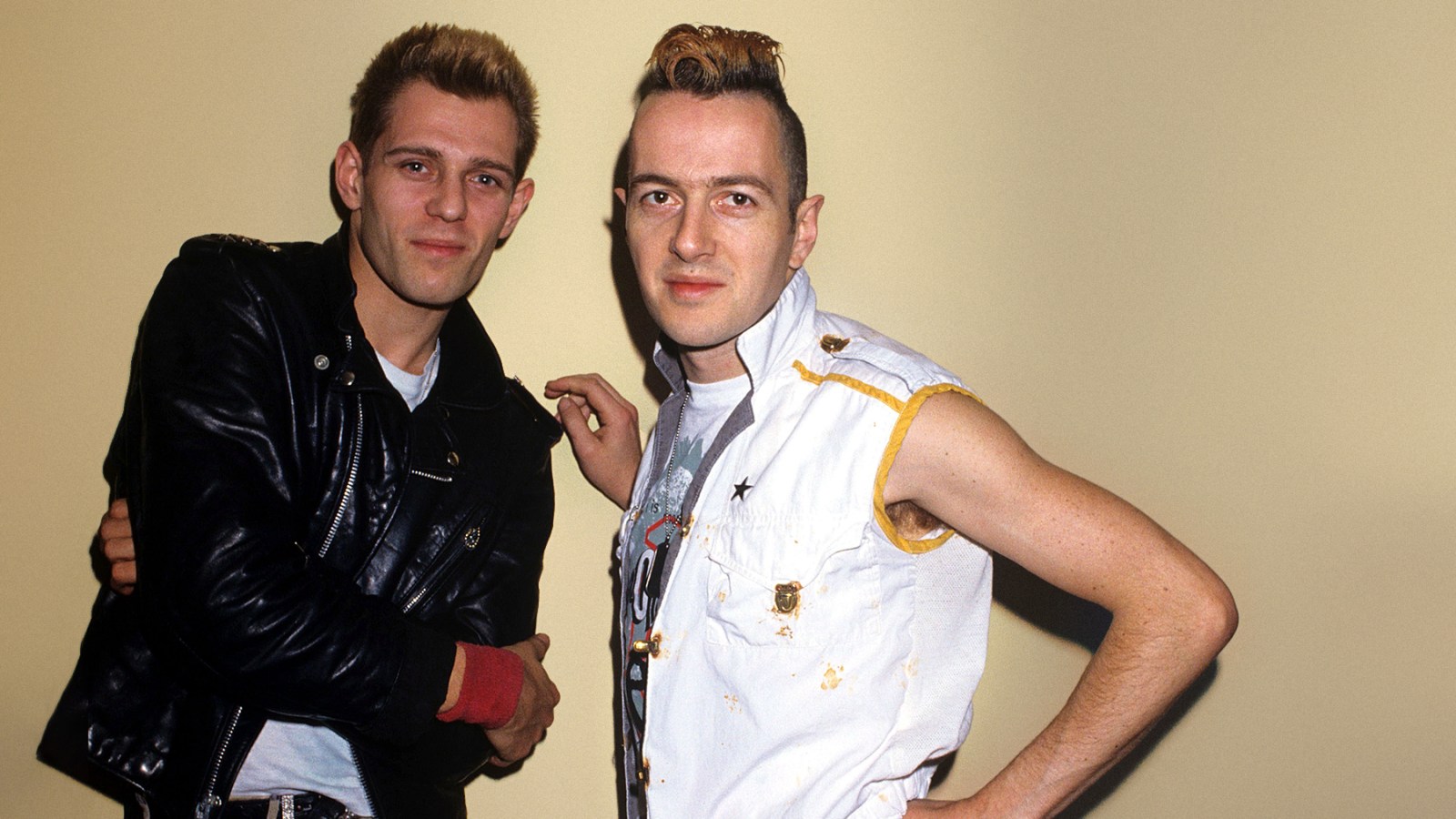

Strummer and Jones originally looked like the heirs to the Jagger/Richards or Lennon/McCartney legacy. They played off each other brilliantly: Joe the hot-hearted blowhard, snarling and slobbering in streetwise rage, while Mick brought a flair for melody and guitar flash. Mick was the one who sang the poppier tunes — “Train In Vain (Stand By Me),” “Somebody Got Murdered,” “Should I Stay Or Should I Go?” Their different styles meshed beautifully, as in “Spanish Bombs,” “Clampdown,” or the unbeatable 1978 single “Complete Control,” where Mick chants the “C-O-N, control” hook while Joe screams his lung out. Joe was the hardcore punk who brought the heart and soul; Mick was the music guy.

But Strummer always had a puritanical zeal about his punk mission and a terror of getting corrupted by fame. Even in the early days, he was defensive about their major-label contract. “Even though we’ve signed with CBS we aren’t going to float off into the atmosphere like the Pink Floyd or anything,” he told Melody Maker’s Caroline Coon in 1977. “I’ve been fucked about for so long I’m not going to suddenly turn into Rod Stewart just because I get £25.00 a week. I’m much too far gone for that, I tell you.” But he turned on Jones in 1983, accusing him of pop heresies that betrayed the band’s punk roots. According to the band’s official statement, “It is felt that Jones drifted away from the original idea of the group.” As Jones told Rolling Stone a couple of years later, “The first thing I did was go home and go boohoo for half an hour.”

In those days, bands had yet to learn the importance of taking time off. Whether it was the Beatles in 1969 or the Smiths in 1987, great bands kept splitting up when all they really needed was a few months apart from each other. The Clash in 1983 were definitely in that category, as Strummer and Simonon kept seething at Jones’ prima-donna airs. “No fun at all,” Strummer complained in the doc Westway to the World. “He wouldn’t show up, then when he did it was like Elizabeth Taylor in a filthy mood.”

But it went deeper than that, because for Strummer, it was an ideological divide between popness versus punk purity. Jones had tried turning the band on to New York club sounds, obsessed with dance music and rap, bringing them into tracks like “This Is Radio Clash,” which now sounded counterrevolutionary to Strummer. “Pop will die and rebel rock will rule,” Strummer predicted in the NME in early 1984, vowing to rid the world of new-wave synth poseurs. “Do you get off on these duos with tape machines? Look. Don’t buy a ticket to the machine show.” For him, Jones’ taste “wasn’t our music. He was playing around with beat boxes and synthesizers.”

Strummer hit the road with his new Jones-free Clash, for the Out of Control tour. Bob Dylan, Strummer’s ultimate hero, loved this lineup of the band. “I think they’re great,” he told Rolling Stone in mid-1984. “In fact, I think they’re greater now than they were.” Better without Mick Jones? “Yeah. It’s interesting. It took two guitar players to replace Mick.”

But Joe was ranting with a weirdly megalomaniacal air — he was newly drug-free, but maybe chugging a little too much coffee on the road. “I’ve been elected,” he told Rolling Stone, slamming his fist for emphasis. “I seriously believe I’ve been elected to say the truth and stamp out all the bull.” During the post-show interview, he gets interrupted by a female fan yelling, “What happened to Mick?” Strummer scoffs, “He’ll be rocking around with some kind of piano nonsense, you’ll see.” But he loses his temper when she keeps going. “I miss him,” the fan says. “Why did you kick him out?” Strummer turns off the reporter’s tape recorder and says, “‘Cause he’s an asshole.’”

As a Clash kid I saw this band in April 1984, in Providence, Rhode Island, and much as I loved Mick Jones, these guys were absolutely ferocious. No radio hits, just the punk bangers, kicking off with “London Calling” and “Safe European Home.” For the finale, Strummer invited the kids to jump onstage and crowd around the mic to sing “Garageland.” They did only three new tunes: “Are You Ready For War?,” “Sex Mad War,” and “Three Card Trick.” Live bootlegs of this tour (like Patriots of the Wasteland or Five Alive) definitely make the case that this lineup had a worthy album in them. Check out this fantastic “Three Card Trick,” from the 1984 Chicago show. [youtube.com/watch?v=tUG7QeONOBU] Whatever you think of Chairman Joe’s Cultural Revolution trip, or his anti-Mick rants, this is a genuinely nasty little Clash song, played by an actual band.

Then compare it to the studio version and weep — on the album, “Three Card Trick” became cocktail reggae with the band replaced by synthesized castanets. Cut the Crap sounded nothing like a rock band — with its digital blare and clown-choir vvocal overdubs, it sounded uncannily like Andrew WK’s 2002 dance-floor novelty “Party Hard.” The keeper was “This Is England,” where Strummer roams the streets over beatbox handclaps, seeing the effects of employment, racism, industrial decay, the Falklands War, and a woman who pulls a switchblade on him and says, “This is England, this knife of Sheffield steel.” But it was too little, too late.

Strummer was humiliated by the whole album. “Some of the tunes were fair but really I hated it,” he told the NME a few months later, in June 1986. “I fell out with Bernie before the final mix — I didn’t hear Cut The Crap until it was in the shops.” He blamed the production on his manager, but took the blame for the songs. “Give me a spliff, a drink, a guitar, a foreign city at night, and let me scribble something,” he explained. “Those are the things that get me. I’m a romantic, not a dialectic theoretician. The rebel chic, the Belfast photos, H-Block T-shirts, and Baader Meinhof shirts; they were all my fault. When you’re gung ho, you’re gung ho, and I was certainly gung ho.”

He also had to see his old mate Mick Jones ride high with Big Audio Dynamite. “I felt terrible when B.A.D. made it,” he admitted. “Not because all the old punks were making it and I wasn’t, I deserved that, I had not acted honourably, but because Jonesy had played me the rough mixes of the album and I said, ‘It’s the worst load of shit I’ve ever heard in my life. Don’t put it out, man, do yourself a favour.’” But Jones didn’t listen to him, wisely, and scored a hit.

It has to be said: Mick was extremely magnanimous in victory. He refused to kick Strummer when he was down, when nobody would have blamed him. “I would never say anything bad about the Clash,” he told Rolling Stone’s David Fricke in late 1985, when the albums were out. “I’ve done a few interviews where people try to get tight with me saying what assholes Strummer and those guys were. It doesn’t work with us. When that happens, me and Don [Letts] immediately jump to the defense of the Clash.” The two old friends made up and reteamed for B.A.D.’s 1986 album No 10, Upping St, writing and producing together—no worthwhile songs, but still a heartwarming reunion.The two old friends made up and reteamed for B.A.D.’s 1986 album No 10, Upping St, writing and producing together—no worthwhile songs, but still a heartwarming reunion.

But Strummer learned his lesson from Cut the Crap. He retired the “Clash” brand name and spent the rest of his life avoiding the spotlight. After fighting so hard to grab his rock-star crown, he let go of it. “I wouldn’t say it was that noble,” he told Musician in 1988. “It’s more like I dropped it on the floor and broke it.” “Trash City,” a minor MTV 120 Minutes hit in the summer of 1988, from the Permanent Record soundtrack, was Joe’s last great shot. But to the Clash’s credit, they became one of the only bands of their era to resist the temptation to do any reunions — no album, no tour, not even a one-off gig. It was a statement of principle that did wonders for their posthumous reputation. By the time Joe Strummer died in 2002 — way too young, only 50, of a heart condition — he was one of the most beloved and respected figures in the music world. It’s one of his greatest achievements that he managed to outlive the curse of Cut the Crap.