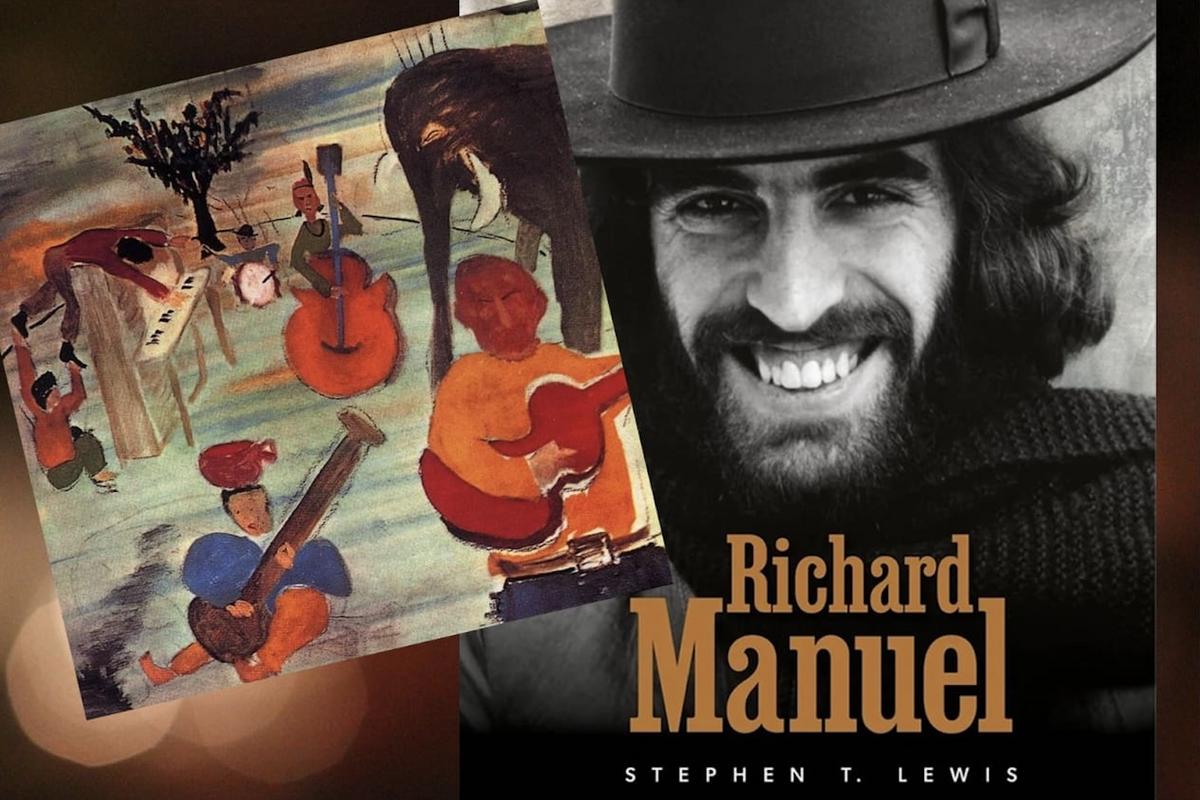

The Band helped reshaped rock with 1968’s rootsy ‘Music From Big Pink‘ – and the late Richard Manuel played a key role.

Stephen T. Lewis’ new book ‘Richard Manuel: His Life and Music, from the Hawks and Bob Dylan to the Band‘ traces his life from youth spent in Stratford, Ontario, Canada to embryonic tenures in pre-Band acts like the Revols. They opened for rockabilly throwback Ronnie Hawkins and soon Manuel was a member of his backing group, the Hawks. There, he met fellow future Band members Levon Helm, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko and then Garth Hudson.

Robertson, Helm and Hudson backed bluesman John Hammond on 1965’s ‘So Many Roads,’ and Hammond in turn recommended the Band to Bob Dylan as he made a then-controversial shift from acoustic to electric sounds. After Dylan came off the road, he and the Band held a series of loose jams before they struck out on their own to record ‘Music From Big Pink.’

READ MORE: Top 10 Songs by the Band

Though Robertson eventually emerged as the Band’s principal songwriter, Manuel was a creative force in their early years. In fact, their gold-selling Top 40 hit debut album began with “Tears of Rage,” a song Manuel co-wrote with Dylan during one of those earlier jam sessions. Here’s an exclusive excerpt where Lewis returns to ‘Music From Big Pink’:

Musically, things were amazing for the group. They were impermeable to outside forces and moved on their own inertia. While the ongoing development of the Band’s songwriting direction was beginning to be curated by Robbie’s collection of Southern and American imagery, just as important a contribution was Richard’s quirky grasp of melody and special vocal approaches.

On Music from Big Pink, Richard composed three original songs and had a cowrite with Dylan, the same number of compositions that Robbie had. The record was a true collaboration in songwriting, instrumentation, and production. Its storytelling diversity enhanced its extraordinary and unselfish blend of writing. The music’s mystery and drama increased because of the multifarious influence of its writers and players.

Richard composed his songs from the inside out. His songwriting reflected a private internal conflict. His songs are unabashed and real. Robbie created characters and told stories. He revealed bits of himself through symbolism and imagery. His writing was more narratively based than personal. He was adept at holding on to a snatch of conversation or an image and building around it for a bigger story.

Richard and Robbie’s collaborations were natural. Their respective strengths negated the other’s weaknesses. Their formative songwriting partnership in the basement was absolutely critical in the maturation of the Band’s sound. By late spring of 1968, it was high time to reap the results of years of hard work, both from the Rompin’ Ronnie Hawkins boot camp and the trial-by-fire Dylan tours.

The Band traveled to Simcoe, Ontario, to Rick Danko’s family farm for a photo session with Elliott Landy. [Manuel’s parents] Kiddo and Pierre drove down from Stratford to stand proudly with their musician son. The group posed in front of the Danko barn with family and friends in a photo called “Next of Kin.” Richard looks confident, strong, and proud to be representing the Manuel kinfolk. The sunny family portrait was featured on the inside of the record, a testament to what was important to the group and a thank-you to the support they had received from their families along the way.

This is how the Band really was. They enjoyed hanging out with their families and each other. They dressed the way they had always dressed; they acted the way that they were.

Music from Big Pink was released on July 1, 1968, a definitive statement of five men who together had traversed the musical landscape of Canada, the United States, and the world. It was a tangible testament to their shared belief in their music, their art, and their mission. For Richard, it represented a 10-year pursuit of musical satisfaction, of friendship, and of a never-ending party. The album’s release was shrouded in mystery and speculation. Was Dylan on the record? What was with that cover? Big Pink? Who are these people?

The music was even more puzzling. The songs swam upstream against all trends. The music was homespun, honest, and strange. The voices hailed from another time and place; it sounded like the singers might have been related. Music from Big Pink was a diverse introduction to the musical mystery that was Bob Dylan’s backing band. The album simmered. It didn’t roar up the charts, but it didn’t need to. It did what it was naturally supposed to do: connect and influence.

More importantly, it reached the Band’s contemporaries. It touched the biggest players in popular music and pushed them to reconsider their musical decisions and directions. The record was a musician’s record, a testament to how far Richard and his bandmates had come. Writer Jonathan Singer later said in Hit Parader, “In a world of flashy clothes and hallucinogenic over-production, Big Pink was a folksy knickknack.” The Band looked odd, sounded different, and was a complete enigma to the mainstream rock media. Pilgrimages were made to Woodstock to find out what the hell was going on in those hills.

Robbie said to Uncut magazine in 2015, “It was just fun. We had lots of laughs. When I think about it now, it’s really the way music-making should be.” The Band released the record like a private joke among friends, and if you wanted to be an insider, you had to listen. In his review for Rolling Stone, Al Kooper named Music from Big Pink album of the year and said, “There are people who will work their lives in vain, and never touch it.”

The reverberations of the music crossed the pond, its influence so immediate that Eric Clapton made plans to disband the supergroup Cream, thinking they had it all wrong. Clapton had heard an acetate of Music from Big Pink at the house of Delaney and Bonnie’s manager and was haunted by what he heard. He immediately thought his current musical station irrelevant. The Beatles’ “Get Back” sessions in January 1969 were a direct attempt to re-create the workshop environment that Dylan and the Hawks employed in Woodstock. The Rolling Stones got back in their own way with a no-frills return to their roots with Beggars Banquet.

The Band’s careful development and sharing of their music and image were a direct affront to the usual happenings in popular music. The Band’s influence was widespread, the plaudits numerous and well deserved.

Guitarist George Harrison was among those who made the pilgrimage to Woodstock to suss out how these guys made their music. The Beatle was enchanted with the Band and told Musician magazine’s Timothy White in 1987, “To this day, you can play Stage Fright and Big Pink, and although the technology’s changed, those records come off as beautifully conceived and uniquely sophisticated. They had great tunes, played in a great spirit and with humor and versatility.”

Top 10 Concert Films

The next time you’re in the mood to watch a classic rock artist tear it up in front of a screaming crowd, reach for one of these movies.

Gallery Credit: Jeff Giles

See Levon Helm in 25 Interesting Rock Movie Facts