For most of the Seventies, Gentle Giant were one of the U.K.’s cult favorite prog-rock bands. They enjoyed moderate success on both sides of the Atlantic, peaking in popularity around 1975 with the album Free Hand, which made it up to Number 40 in the U.K. and Number 48 in the U.S. It was just enough success to build a loyal following for themselves and put them in proximity with the era’s mainstream rock hit makers.

In frontman Derek Shulman’s new memoir, Giant Steps: My Improbable Journey From Stage Lights to Executive Heights, cowritten with Jon Wiederhorn, he reflects on his own legacy, which included encounters with Black Sabbath and Jethro Tull early on. He also recounts his transition to working behind the scenes at various record labels where he worked with Bon Jovi, Slipknot, Pantera, AC/DC, and other acts.

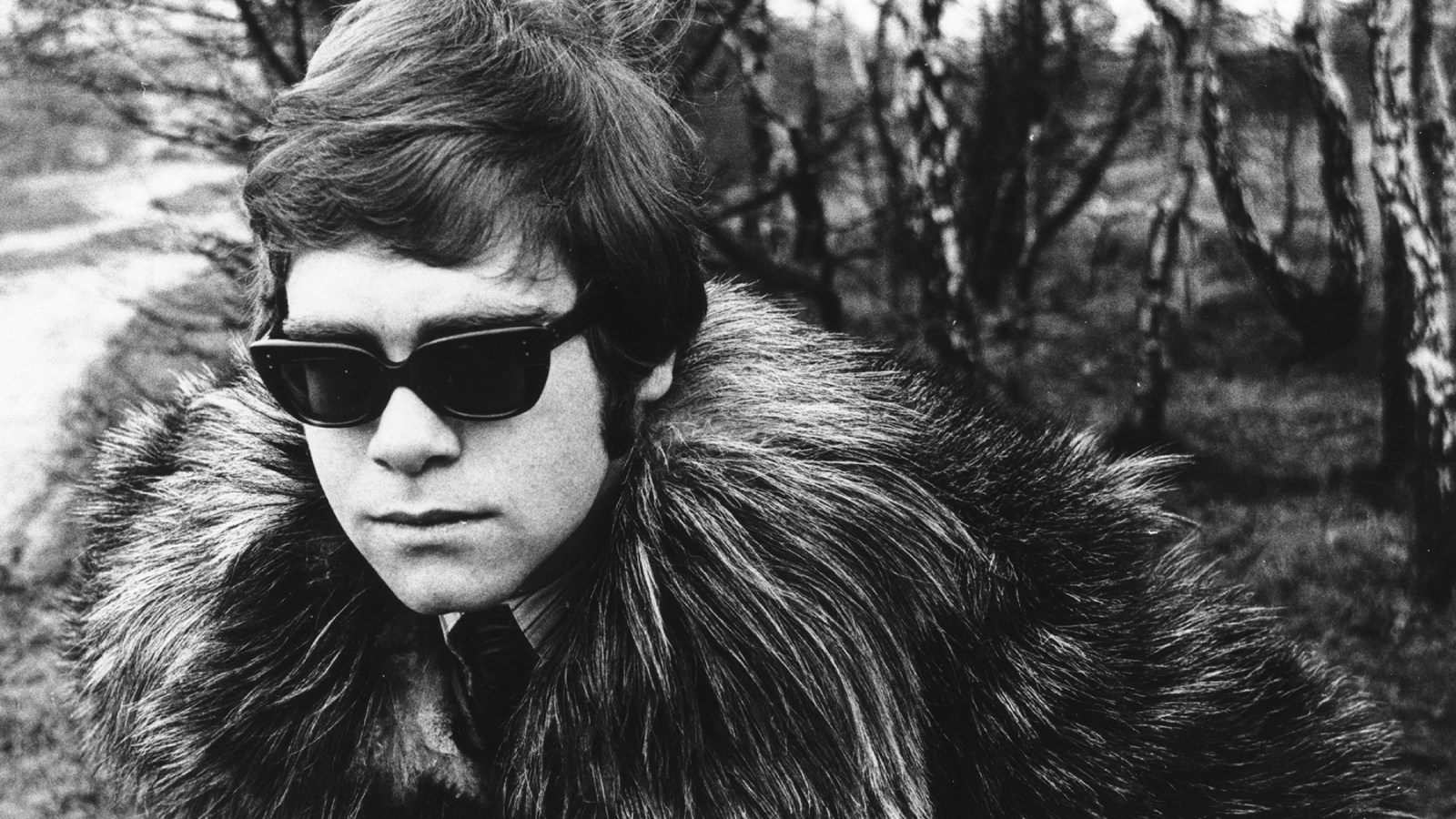

In an exclusive excerpt from Giant Steps, Shulman recalls his pre–Gentle Giant days when a young piano upstart named Reginald Dwight filled in for a spell with Shulman’s psychedelic rock band, Simon Dupree and the Big Sound, in 1967.

A minor historic moment in the career of my first real band, Simon Dupree & The Big Sound, happened in July 1967. Right before we toured Scotland, keyboardist Eric Hine came down with glandular fever, so his doctor grounded him from touring. We needed a replacement right away. Elton John was just starting out—only at the time, he was still going by his birth name, Reg Dwight. He was managed by a guy named Dick James, who had him working under a retainer of £10 per week.

Ray and I went to London to meet Reg, and he was incredibly nice and very humble. Of course, it’s hard not to be humble when you’re making less than £2 a day — something we had no way of knowing at the time. We asked him if he would play something for us, and, without a pause, he launched into a litany of piano music: blues, American standards, British pop. It was like someone had tossed a nickel into a player piano.

‘Can you play organ and Mellotron?’ I asked.

‘Sure, if it’s got keys, I can play it.’

‘How about weird, psychedelic stuff?’

‘Yeah, mate,’ he said. ‘No problem.’

It was clear he’d be able to play anything we threw at him, so we asked him to fill in for Eric on tour. ‘Hey Reg, what we can offer you is £25–30 a week,’ I said, hoping he wouldn’t ask for more.

‘Holy shit!’ he shouted. ‘Really? I’ve never seen that kind of money.’

We would never have guessed that this was almost three times what he was making, but we were happy to pay it. He was a fine keyboardist, and he was saving our asses. After we met Reg, we went home, then he came down to Portsmouth to rehearse with us for a few days before the tour. Reg was chatty and open with us, and we grew close in no time. He wasn’t out of the closet yet, and it wasn’t long before he unloaded some personal shit on us. He had a girlfriend who wanted to marry him, and he didn’t know if he loved her as a friend or as more.

Reginald Dwight, who later became Elton John, on tour with us in Simon Dupree & The Big Sound in Scotland, 1968.

Courtesy of Derek Shulman

‘I dunno what to do,’ he confided in us. ‘I don’t really want to get married. Should I get married, should I not get married?’

We liked Reg but we barely knew him. How could we possibly give him advice on something so serious?

‘You know, Reg, I’m sure you’ll do what you have to do,’ I said. I knew it was hardly constructive advice, but it was the best I had.

‘Yeah, fuck it,’ he said. That was the last we heard about the subject.

Reg knew a lot about pop music and loved talking about his favorite groups. He wasn’t just knowledgeable about English music. He knew just as much about what was happening in the States, though neither of us had been there yet. We bonded on the black blues we all listened to on the American Air Force Radio.

Some of the shows on the Scottish tour were in nearby towns. Others were a hundred miles or more apart, which required long drives in the van. Every few hours, we’d stop at a café to take a short break, have a coffee, and maybe take a piss. And then we get back into the van and head back out. That’s when we learned another quirk about Reg.

‘Hey guys, look what I’ve got,’ he said one day, shaking a snow globe that probably cost about £5.

‘Reg, why do you want that? Isn’t it a little pricey?’ I said.

‘Maybe. I dunno. I just wanted it.’

So it went every time we stopped. Reg always picked up something odd: commemorative spoons, a yo-yo, a candlestick. And he never worried about the price. Once, he picked up a watch that looked expensive. I figured maybe I should talk with him before he spent his entire per-diem for the week.

‘Do you think you should think about whether you really need something before you buy it?’ I asked. ‘I mean, especially if something costs a lot and you don’t need it on tour.’

‘I like to collect stuff,’ he replied, nonplussed. ‘It’ll remind me of being on tour when I get back home and look at the stuff. Why, do you want any of it?’

‘No,’ I said, and I laughed.

I kind of felt sorry for Reg. He seemed unable to stop himself from buying useless things. Pretty soon it wouldn’t matter, and he’d be able to buy anything he wanted.

We stayed friends with Reg after Eric returned to the group, and we frequently talked about working together in the future. Meanwhile, we swam forward with Simon Dupree, but at times it was more like treading water. We started to talk more to our brother-in-law and manager, John, and everyone at EMI about heading in a different musical direction. Understandably, they weren’t too keen on the idea.

In an effort to appease us, John booked us a session at Abbey Road in mid-’68 to record something more experimental than anything we had done and release it under another name. Ray, Phil, and I wrote a weird song called ‘We Are The Moles,’ which we structured in the style of the Beatles at their trippiest. We played droning, spacey riffs and phased the instruments in and out of the mix. We layered chiming keyboards on top and added freaky studio sound effects to the vocals, which included lines like ‘We are the moles and we stay in our holes / Hiding our faces, revealing our souls.’ We didn’t take it seriously at all. We just had fun, and there was a fast vocal part that was a little like ‘I Am The Walrus,’ which we all thought was great.

It was easy to do, and we did it quickly so we would sound spontaneous. We had a good time tapping into this strange, surreal side of ourselves. When we’d finished it, we recorded a B-Side, ‘We Are The Moles Part II,’ which started with marching sound effects and then turned into this ethereal, nonsensical ditty with the three of us harmonizing the only line in the song, ‘We are the moles,’ in various ways. It ended with madcap clapping and calls for ‘More!’ which Ray and I found hysterical. We wrote the whole thing in the studio in five minutes and recorded it in 10.

Parlophone released ‘We Are The Moles’ in 1968, and, to our surprise, it started getting airplay. The press was chattering. Everyone was trying to figure out who was in this mysterious band with no credited members. The song hit the Top 100, and when people started wondering if The Moles were The Beatles in disguise, it reached #75 and started going up the charts. We thought this might be the beginning of an anonymous side project that would be fun to do and imagined going back into the studio to record a whole album of silly, psychedelic songs.

That was before Syd Barrett burst the bubble. In an interview with the weekly Melody Maker music paper, he said, ‘The Moles are just that shitty group Simon Dupree & The Big Sound.’ Once he’d intercepted our galactic flight, the engine stalled, and ‘We Are The Moles’ dropped right off the charts. It was such a dick move. Rather than allow the mystery around us to build — at no expense to him — he ratted us out.

Having the mysterious shroud of the Moles yanked off instantly halting our forward momentum was aggravating and made us want to escape the back-stabbing English pop scene and do something more obscure that catered to our musical interests instead of the fickle tastes of the mainstream… Of all the pop stars we knew, Elton John might have played the biggest role in the Shulman brothers’ transition from Simon Dupree & The Big Sound to Gentle Giant.

Reg was an incredible music scholar and collector. He listened to everything that was going on in Europe and America. When I told him we wanted to play a different kind of music, he suggested we listen to some bands for inspiration. One of them was Spirit. We checked out their first two albums, Spirit and The Family That Plays Together, which combine a bunch of musical styles including psychedelic rock, jazz, blues, and folk. It was intriguing, inspiring, and not that dissimilar to the kind of music we were already considering. Elton also suggested we listen to Frank Zappa and Miles Davis, two other artists we grew to love.

Simon Dupree & The Big Sound promo shoot for ‘Kites,’ 1967.

Courtesy of Derek Shulman

At one point when we were still doing Simon Dupree, Reg told us he was a songwriter as well as a pianist and he’d love to write a song for us. We had enjoyed touring with him, so we said we’d love to hear anything he came up with. The next time we saw him, he played us a really good song on the piano called ‘I’m Coming Home,’ and we went right into Abbey Road studio and recorded it for a future single.

Then we got caught up in a whirlwind of angst and drama. I was ending my engagement, we were becoming disenchanted with the band, and we were talking about breaking up. So, ‘I’m Coming Home’ never got released, and it fell through the cracks for decades. Then, in 2021, I saw that Elton was playing in New York, so I called his agent Barry Marshall, who, funnily enough, used to book Simon Dupree & The Big Sound. Barry got me two tickets, and before my wife and I went to the show, I tracked down the recording of ‘I’m Coming Home,’ which I had on a cassette tape. I gave it to Elton backstage after the show. He hadn’t remembered doing it with us and said he couldn’t wait to hear it. The next time I talked to him, he told me he loved the song and that it brought back some great memories of being on tour and hanging out with us.

Rewind back to 1969. I’m talking to Reg about finding musicians for our new band, and he says he has written a bunch of new stuff and might be interested in joining us. ‘That could be really great,’ I tell him, and we agree to get together to listen to his new songs. Ray and I met Reg in London, and we were excited to hear what he had put together. As much as we wanted to work with him again, as soon as he started playing the tape, we knew the music wouldn’t fit our new direction. His new songs were good, but they were rooted in R&B and pop, and that was exactly what we wanted to get away from. We knew that he still wanted to play commercial music, and if he joined our new band, he wouldn’t be happy. We told him we didn’t think it would work, and he was gracious about being gently rejected.

We changed the subject and kept chatting, and Reg told us he wanted to change his stage name, too.

‘Oh yeah?’ I said. ‘What are you thinking?’

He told us he’d chosen the name Elton John because he was a big fan of Soft Machine, whose sax player was Elton Dean. And he got the surname John from the vocalist Long John Baldry, with whom Reg had played in the band Bluesology.

‘Reg, that will never work!’ I spouted. ‘What a stupid name that is.’

‘Maybe you should come up with something else,’ said Ray, who was trying harder than I was not to laugh.

Not long after that, the music Reg wrote with lyricist Bernie Taupin started to take off. By 1970, ‘Your Song’ was a major hit and ELTON JOHN was playing to packed houses at the Troubadour while we were scrambling around Guilford trying to get gigs. Clearly, Reg had the last laugh.

This is an edited extract from Giant Steps: My Improbable Journey From Stage Lights To Executive Heights by Derek Shulman, published by Jawbone Press. Text © 2025 Derek Shulman