I

n the end, I always thought about his Birkenstocks. I’d often glance over at them during our interview, both of our pairs positioned next to each other on the studio floor, below the couch where we sat. Those are Bob Weir’s Birkenstocks! I thought. But he didn’t pay attention to the sandals, which had become his signature look in his later years. He was busy playing ball with my questions the best he could, stroking his beard and sipping on a glass of Coke. He gently opened up to me, the ice clinking around as he dug into his box of memories. I had no idea he’d be gone in less than a year.

At 77 — huddled inside A&R Studios, part of the historic Jim Henson studio lot that his bandmate John Mayer had recently purchased — those memories were still fresh. Sure, he needed that glass of Coke during a break in the interview, a sugar boost after he admitted he was “starting to fade a little bit.” But he was as sharp as ever, talking about stories that stretched back to the Sixties as if they’d all happened last week. At the same time, he was juggling several events in the present to honor his band of 60 years, from the Kennedy Center to the MusiCares celebration, just before Dead & Company returned to the Sphere in Las Vegas for another residency. But he was nonchalant about it all. “I’m the same guy,” he said. “I still have to get out of bed in the morning, and my back’s cranky. Nothing much has changed.”

That was Bobby, avoiding praise and pride at all times. He joined the Grateful Dead when he was 16, so he was the baby of the family, a little brother figure to Jerry Garcia (the band had to promise Weir’s mother that he was still attending school). And even decades later, after several of his bandmates were gone (Bob preferred the term “checked out”), he still had a youthful, impish charm about him. If he felt any pressure about carrying on the band’s legacy, he never let any of us see it. That’s why our hearts are aching over his death at 78. The Kid, as the Merry Pranksters called him, has left us.

Weir died on Saturday, the 10th anniversary of David Bowie’s death (there’s not all that much musical crossover between the glam legend and the Grateful Dead, but you’d better believe my beloved Dead redditors made this excellent graphic). Many of us were busy remembering Bowie, but I’ll admit that I woke up thinking about Weir. I was oiling some cutting boards in my kitchen and listening to “Jack Straw,” as one does on a Saturday, thinking about how quiet he’d been lately. He didn’t perform his annual New Year’s Eve shows with his band the Wolf Bros in Florida, hadn’t posted any recent workout videos. And he had no tour dates on the books. I hoped he was doing OK. Hours later, when I received the news, I realized it was Saturday night. Of course it was.

I had been chasing Weir down for an interview for years. I envisioned us working out, doing deadlifts together in the gym, or meditating on some distant mountaintop. But our time together at the Henson lot was better than that. I had recently befriended his daughter Chloe, a talented photographer who spent countless nights documenting her father onstage. She was eager to introduce me to her dad and his lovely wife Natascha, who hung out in the studio with us during our interview. It gave me a sense of who Weir actually was. To him, the music always came second to family.

Though Weir had indulged in plenty of substances in his past — he once took LSD every Saturday for an entire year — he was healthier than most rock stars, and had overcome past scares. As Rolling Stone contributor David Browne wrote in his 2015 book So Many Roads (a bible for any serious Deadhead), Weir was on a macrobiotic diet back in the Haight-Ashbury days. He could be seen eating seaweed in the kitchen of the Dead’s famous house in the neighborhood, chewing incredibly slowly. And when the band’s home was raided by the cops in 1967, he was busy upstairs, practicing yoga.

Weir was also incredibly funny. He used phrases like “He’s more fun than a frog in a glass of milk” and once drove around with a duck in his arms and a glass of champagne, as seen in the wacky video for 1987’s “Hell in a Bucket.” He was also excellent at one-liners. During that ’67 drug raid, when he was escorted out of the house in handcuffs, he yelled, “As they say, just spell the name right!”

Weir was often called “The Other One,” the rhythm guitarist who molded perfectly around Garcia and bassist Phil Lesh, grounding the melody while allowing for cosmic exploration. “He’s an extraordinary original player,” Garcia once said. “In a world full of people who sound like each other, he’s really got a style that’s totally unique. I don’t know anybody else that plays the guitar the way he does.”

To Bob Dylan, whom the Dead toured with in 1987, Weir was “a very unorthodox rhythm player. Has his own style, not unlike Joni Mitchell but from a different place. Plays strange, augmented chords and half chords at unpredictable intervals that somehow match up with Jerry Garcia — who plays like Charlie Christian and Doc Watson at the same time.” Or, as Weir simply told Rolling Stone in 2015, “Some people were born with perfect pitch. I was born with perfect time.”

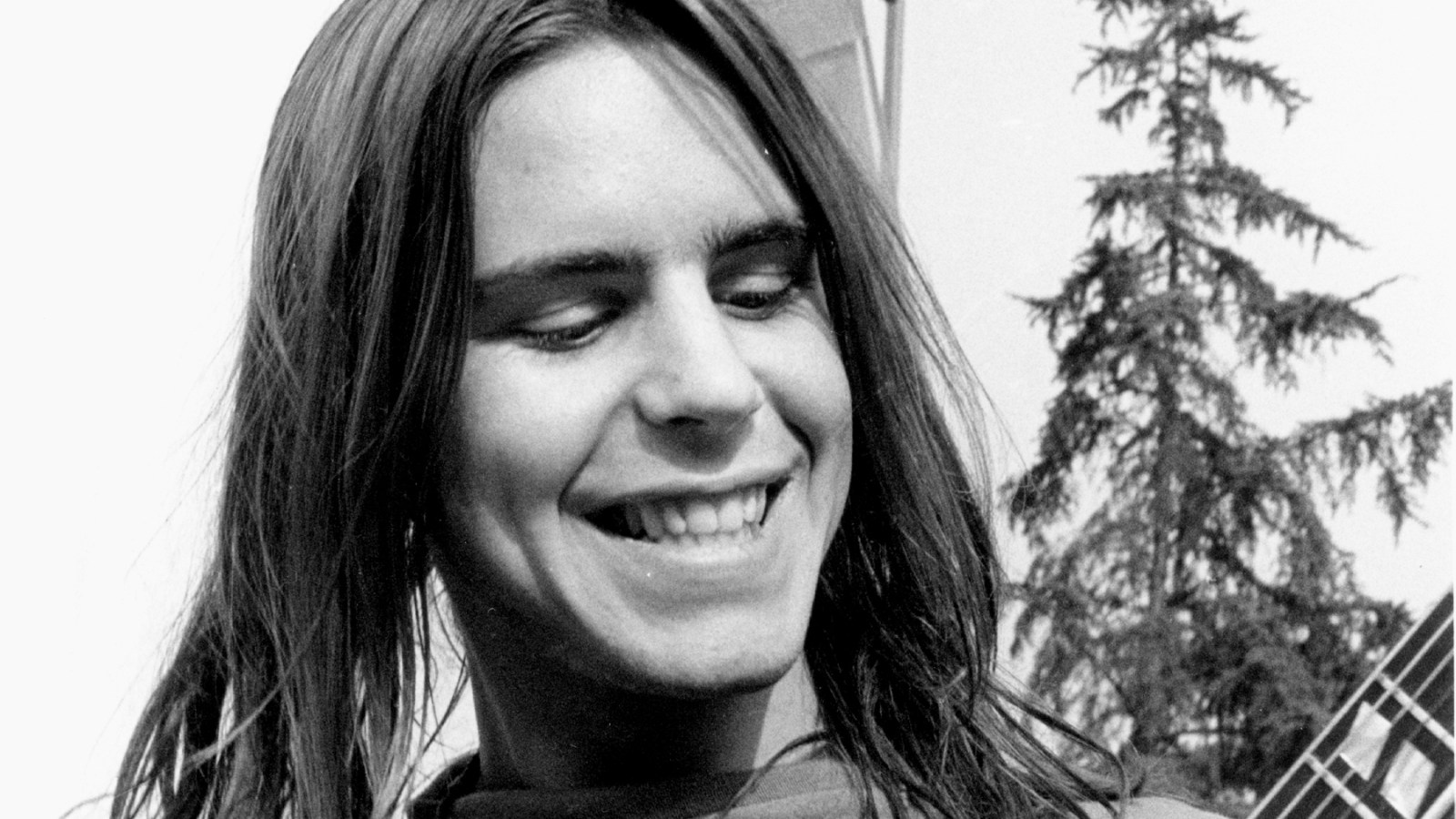

It was no secret that Weir was also the most handsome member of the Grateful Dead, responsible for bringing women around. “There’s beautiful Bobby, surrounded by the ugly brothers,” Dead songwriter John Perry Barlow joked in the excellent 2015 documentary The Other One: The Long Strange Trip of Bob Weir. “If you’re gonna go to bed with somebody from the band, is it gonna be Pigpen?!” Garcia used to joke that this is why they put up with all of Weir’s shenanigans, and that probably includes his often-discussed denim shorts phase of the Eighties. (He chalked that look up to the heat: “It’s always July under the lights,” he said.)

Describing Weir as “The Other One” stopped making sense after Garcia’s death in 1995. Whether in the Wolf Bros., RatDog, or any Dead offshoots like the Other Ones, the Dead, Furthur, and Dead & Company, he became the keeper of the flame for the 30 years that followed (alongside drummers Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann, and Lesh before he died in 2024). Weir practically lived on the road, touring nonstop since 1965, ensuring the Dead’s music lived on.

“One of the things that I hope that I’m remembered for is bringing our culture and other cultures together — by virtue or by example of,” he told me. “I’m hoping that people of varying persuasions will find something they can agree on in the music that I’ve offered, and find each other through it.”

During our time together, Weir told me he was finally making headway on the memoir he’d been working on for years, fittingly titled It’s Always July Under the Lights. I wonder how much he completed, and if we’ll ever get to read it — a look inside his weird and wonderful brain, one last time. “I look forward to dying,” he said proudly. “I tend to think of death as the last and best reward for a life well-lived. That’s it. I’ve still got a lot on my plate, and I won’t be ready to go for a while.”

It’s the kind of quote that startles you when you re-read it, almost like he knew he was nearing the end. But that’s not really what stays with me when I revisit our chat, hours after he’s checked out. What I come back to are those Birkenstocks, and how he told me he’d recently abandoned them to run barefoot on rocky roads outside his home. In touch with the earth, in motion, forever. “I think that’s a great way to get grounded,” he said. “It’s a practice that’s amounting to something for me.”