This story was originally published in the May 4, 2007 issue of Rolling Stone.

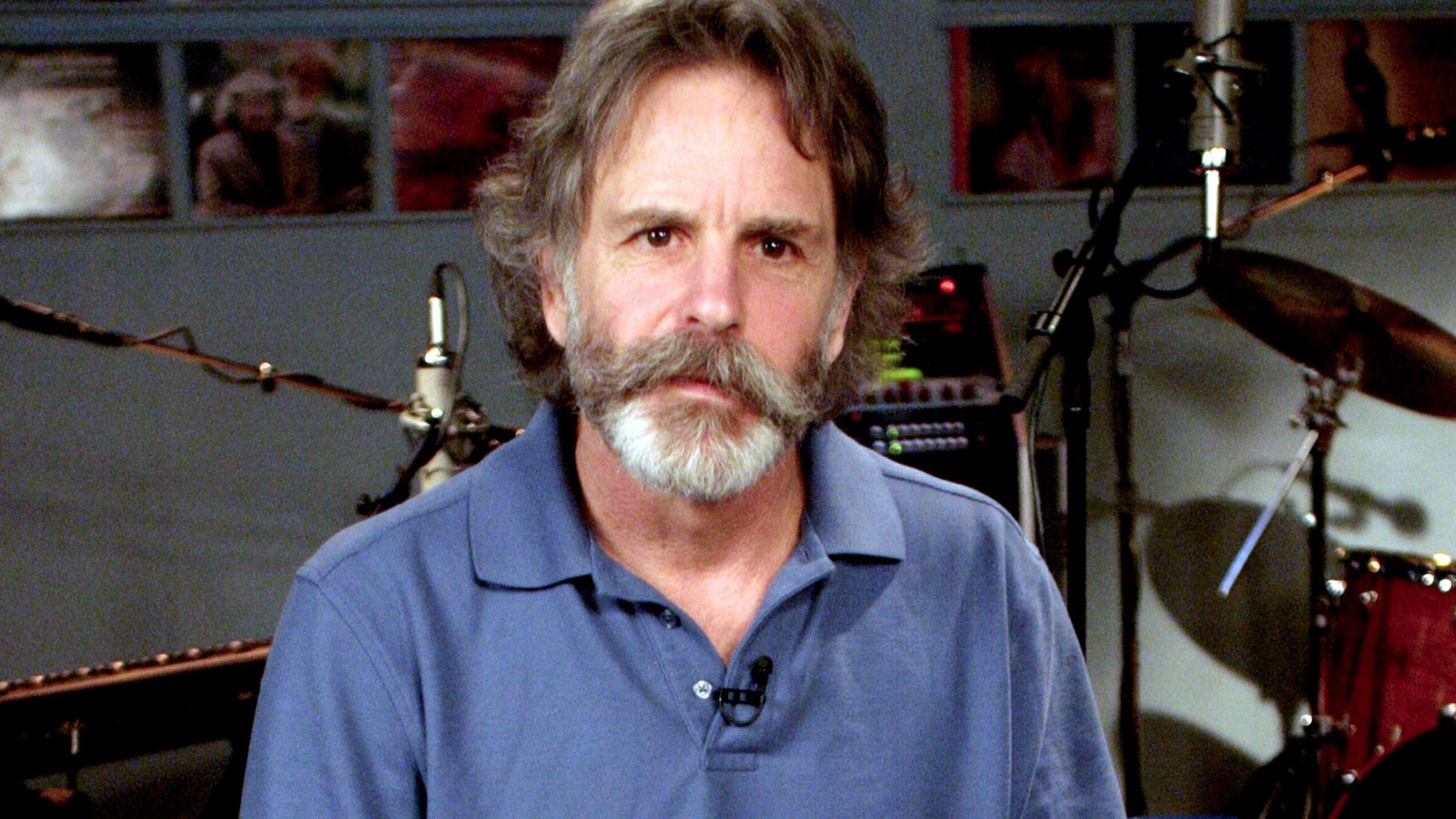

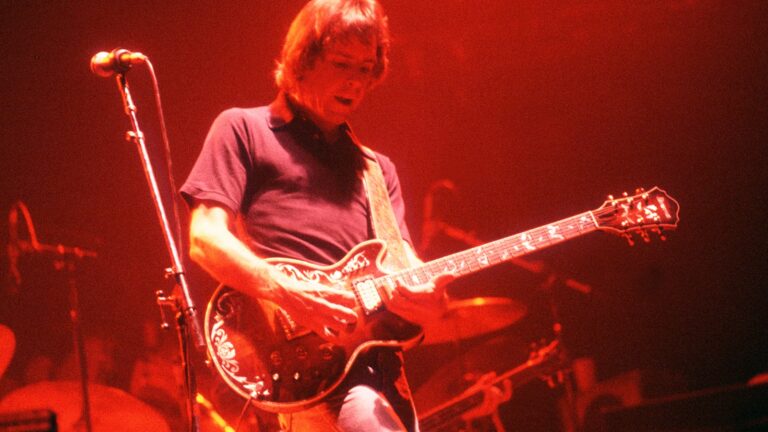

For Rolling Stone’s 40th anniversary, the editors interviewed 20 artists and leaders who helped shape our time. In this Q&A, David Fricke talks with the Grateful Dead‘s Bob Weir.

Do you see any signs of the energy and magic of 1966 and ’67 in San Francisco today?

The foliage and shrubbery in the Panhandle — that brings me back a bit. What’s gone is all the craziness, the hysteria. San Francisco now is a service-industry city. The people are young, upwardly mobile professionals of one sort or another. You get a more creative set of those folks here than in most places. But the times are completely, different. Young people in San Francisco or anywhere else are connected with New York, Mumbai and their folks back home in Iowa. They talk to everybody on that circuit daily. Back then, when you made a long-distance call, it cost some change. You picked and chose your occasions. Now, information exchanges happen so fast and furious — it’s as if there were no locations anymore.

One thing about San Francisco: Politically, we’re still out there. We elected a mayor [Gavin Newsom] who pisses off a lot of the old guard. We still have that forward thrust. People that come here get steeped in that: “Why shouldn’t gay people get married? And a little poetry with your coffee?” That’s not a bad idea.

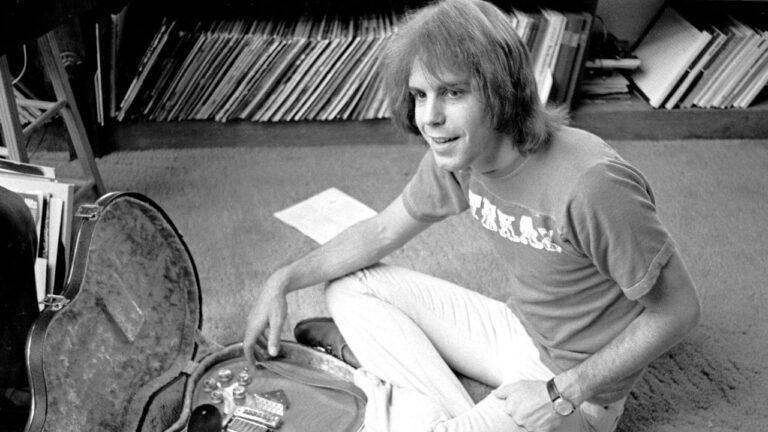

You were a teenager when you first met Jerry Garcia and started playing music in the Bay Area. What was it like to be in San Francisco at that age, at the dawn of psychedelia?

This was always a mythic city for me, growing up down in the peninsula. Then when I got old enough to dive in, it was way beyond just being a kid in a candy store — to the point where, at seventeen, I realized I’ve got to take a deep breath and step back, that there was too much going on for any human to handle. The interaction in the city was furious. I had to mature immediately.

You were much younger than the rest of the Grateful Dead when the band started. Were they protective of you?

In some ways, I think they envied me, because I had so little in the way of preconceptions. They figured, “This guy is going to turn up some stuff we wouldn’t.” And they had faith in my toughness, I could roll with a punch. I was the guy who got beat up by the cops the most. The band would bring me back to the house and say, “What was it like?” And I’d tell them, “This is what you don’t want to say to a cop.” We all had our place on the team. We weren’t so much looking out for each other as watching and learning from each other.

In a way, you were one of the original teenage hippie runaways. How hard was it for your parents to accept that?

They saw the train coming, and they tried to stop it. They were straight-ahead, rock-ribbed Republicans. They tried to keep me in school. And I got a great education. I can talk circles around a lot of people with four years in college, and I ran away in the middle of junior year in high school. I loved my folks. They were my adoptive parents, but I loved them, and they did their very best by me. What they did manage to impart to me was to be kind, to be considerate. My dad taught me to be a gentleman. And my parents instilled in me the importance of applying myself. That all stuck. A couple of years later, I started bringing home gold records.

Despite the anti-establishment aura of the Dead, the band actually lived and worked together like a traditional family, especially at your famed house at 710 Ashbury.

Life was extremely communal. The most important thing was keeping each other amused. That was job number one. We were on something of a gravy train. We made enough money from gigs to feed everybody and pay the rent. And everybody just took care of what they saw needed taking care of. I kept the kitchen clean, because I used to cook a fair bit. And we practiced a lot.

Later, the Dead applied those family values to running your own label, touring business and management. What were the best and worst things about being a corporation?

At one point during the Seventies, we found ourselves carrying briefcases. We got over that in a big hurry. We had to invite in people who had a little better business sense. The roughest part about our corporate model was we were good to our employees, but to a fault. We would hire people that

would have been unemployable by other folks. But they became part of the family. Unfortunately, when Jerry checked out [the guitarist died in 1995] and the business had to substantially downsize, I felt bad because many of them had nowhere to go. And we couldn’t support them.

Were the Dead’s ideals and corporate reality simply incompatible?

I just don’t think we got it right. We were musicians. Mick Jagger came out of a business school [the London School of Economics]. What he was able to assemble around the Rolling Stones had more integrity, more functionality, than what we did. We did well enough financially, so it didn’t matter if we weren’t particularly efficient.

In its first issue, Rolling Stone published a now-famous photo of the Dead on the front steps of 710 Ashbury after police raided the house. [Weir and organist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan were among eleven people arrested on drug charges.] How important was the magazine to the community in 1967 and ’68? In a sense, it was a local paper then.

It was the voice of us. It was done with journalistic integrity, and it legitimized what we were up to. There was opinion involved. We yukked it up over various writers’ opinions of this and that. But it was gratifying to have somebody documenting what we were about — in a straightforward way but sympathetic in their understanding, whereas someone from Look magazine would miss a great deal of the nuance.

Did the Dead — and San Francisco at large — feel betrayed when Rolling Stone moved to New York in 1977?

We didn’t care for that much. We felt like it had been ripped out of us. We liked having it here. At the same time, there was every reason to go to New York. The pulse of San Francisco had been squashed underground. There was not much argument with that. And their move happened at the same time that we were all moving out of the city. It was time to duck for cover. There were nothing but toothless speed freaks on the streets.

The Dead’s audiences in the Sixties and early Seventies were united against the Vietnam War. Are you disappointed that the crowds you play for now, when you tour with Ratdog, have not protested the Iraq War with the same energy?

It’s a matter of media. When we moved into 710, we put a TV in the living room. We would watch the news and see the bodies coming back [from Vietnam]. We don’t see bodies coming back these days. The carnage is the same. But we don’t see it on TV. The politicians don’t want the full visual impact of the war, what it’s costing this country in human lives, coming back here. So people aren’t as galvanized. That was a very astute move — not in terms of wise, but in terms of conniving.

Why did the Dead never write or play topical or protest songs in the Sixties? Even when you covered Dylan, it was his emotional broadsides, like “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.”

We had a distaste for using the stage as a pulpit or a podium. If we had politics, that was our business. But the stage was sacred. We were artists, not megaphones. And we were human, given to mistakes.

How would you describe your own politics today?

I’m progressive. We need to see to our schools and infrastructure, in a big hurry. We need to be more generous abroad, because we’re perceived by most of the world as hoarding. That’s not the way I like to feel about myself: The Dead did our share of political benefits. If somebody had a basketful of good ideas and a focus we admired, we would play for them. I try to register voters now and get them pointed at the polls. If we do that amongst the jam-band audience, that will have great political consequences next year.

l was surprised to see recent photos of you backstage with Donald Trump and the conservative writer Ann Coulter. Don’t you find it strange that either of them would go anywhere near the Dead zone?

Ann’s a big fan. All I can say is, it takes all kinds [laughs]. They’re welcome to my shows. Everybody’s welcome. The night Ann Coulter was there, I had friends who were aghast — “You’re going to let her in?” C’mon, don’t you want to stand next to the person and see if you can feel anything, feel her humanity? I gotta at least see if she has any humanity about her. And she does.

What did the Sixties ultimately accomplish? What kind of world has been left by your generation to its children?

Let’s get into the downside first. My generation almost let democracy disappear in this country — by not voting, by getting lazy, by going to sleep. Everybody took a big snooze after that huge event in the Sixties. And very few people woke all the way back up.

Then there’s the environment, on account of that big snooze. Yeah, we started Earth Day way back when. [The first official Earth Day was proclaimed in San Francisco in 1970.] But what has it bought us? Look at global warming. That could be curtains. I was trying to bring deforestation to the fore in the Seventies and Eighties. And even people of my own ilk — they’d come to the benefit concerts to see the artists and hear the music. They might cut a check. But they had their jobs to do, their families to care for. Nobody was looking down the road. Nobody was looking at their grandkids. So it’s gotten way bad, way worse.

What’s the upside of the Sixties?

The upside is that we know that thing is there. Whatever that was, it’s there. We know what it felt like. And some of the fresh faces I see in the front rows at Ratdog shows today — they feel that. It’s not different — it’s the same thing. What we had then was timeless. It comes and goes, ebbs and flows. But I think they can feel it. It doesn’t have to be a huge deal. It just has to be there, to provide enough juice for enough people to coalesce around and work together, to bring about meaningful, fundamental change.

How have you changed — personally, emotionally —since your glorious hippie youth?

[Long pause] I don’t know if there’s much that’s different now I’ve basically been a professional adolescent all my life. I couldn’t have been more fortunate. What worked for me then — that outlook still works for me now It could come crashing down tomorrow. I may be unprepared for something that’s right around the corner. But I haven’t changed that much. I still keep my eyes as wide open as I can. And I have as much energy to get into as much different stuff as I did when I was in my teens and early twenties. I always took good care of my body.

What’s changed?

I’m a dad. That’s fundamental. Watching your kids grow, you go back a bit. You can watch a bug crawling around for minutes at a time — just sit and marvel at its complexity, the utter bugness of it. I’ve learned to do that again. So maybe I’m not such a professional — or perpetual — adolescent anymore. I’m now a kid.

Has becoming a father made you more aware of what you put your parents through when you took off to join the Dead?

Absolutely. But even at that point, I was aware that they wanted nothing but the best for me. My folks were trying to get it through my thick skull that music is wonderful, but you can’t make a living doing that. They were telling me I can’t be that lucky. They were wrong. But they knew I didn’t hold it against them.

Do you think you will be more open and trusting when your daughters reach that age of discovery? We’ve got our best guys on it [laughs]. I held off for a long time before I had kids. My ardent hope is that I’ll be too old to care.