C

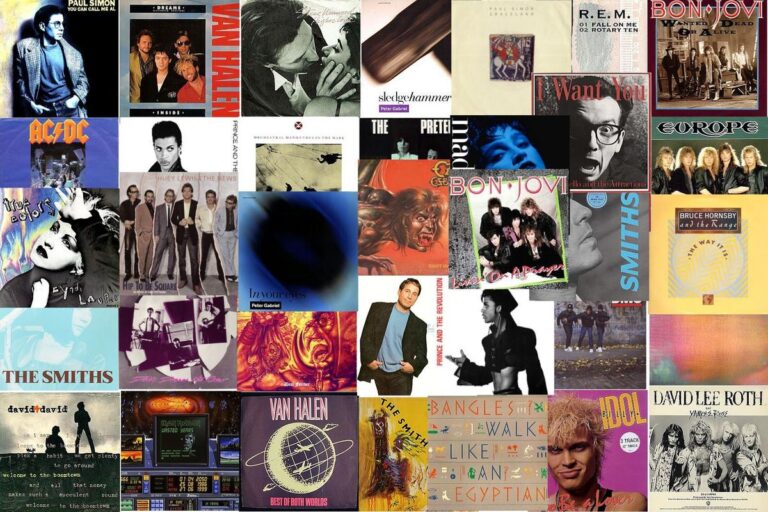

harlie Puth’s Whatever’s Clever!, due March 27, is his fourth album, but in some ways, it feels more like a debut. The collection is his best work yet, built around an entirely new approach — airy, jazzy, live-instrument-driven production that tends to land somewhere between Bruce Hornsby’s “The Way It Is” and Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature.” Puth is 34 now, married, with a baby on the way, and he’s finally found his full footing after making music that didn’t always live up to his potential. His second album, 2018’s Voicenotes, with its Quincy Jones-meets-Babyface R&B classicism, was a high point, but he had a habit of overthinking his music, dropping between-album trial-balloon singles that tended to fall short. Critics “panned my music for no consistency or whatever,” says Puth. “I admit, at points, they were right.” In jazz-club residencies in New York and L.A. last fall, Puth previewed songs from the new album, and recast old hits from “Attention” to “We Don’t Talk Anymore” in arrangements that exploited his considerable skills as a keyboardist and bandleader. (He laughs off speculation that he was sending a message by singing the latter song, originally a duet with ex Selena Gomez, around the time of her wedding: “Why? Because I played it? I’m not gonna change the set list!”) A major tour, which will include his first headlining show at Madison Square Garden, will expand on those club dates. “I want to take the experience I had at the Blue Note and make it built for arenas, but still intimate and small,” he says.

As he prepared for the biggest year of his life — with the tour, album, a performance of the national anthem at the Super Bowl, and the birth of his first child — Puth sat down to talk about how he got here, including a certain shout-out from a pop superstar.

Your new album feels like an artist really finding himself. One of the steps along the way was a very public moment, when Taylor Swift sang about you on The Tortured Poets Department: “We declared Charlie Puth should be a bigger artist.”

It was pretty shocking. I don’t know if that was the moment where I realized that I needed to write a certain kind of music, but it was definitely affirming that one of the biggest stars in the world knows me. It’s like, “I better write something good, ’cause maybe she, and some others, will hear it.”

Right after you heard about that, you decided to release “Hero,” which you described as the first single from your new album — but it’s not on this album.

Yeah. What the hell was I talking about? I think I sometimes just get a little ahead of myself. I wasn’t ready to put out an album at that point.… I sat with myself and thought maybe I should, for the first time in my career, actually make an album. I’d never sat down and said, “Let’s make an album and then release it.” It’s always, “The song’s doing well, we need to put it out. And while I’m doing radio promos and whatnot, going on TV, I’m going back to my hotel and making an album.” This album, Whatever’s Clever!, is the first time where I just sat down and I had a lot of time. I just stayed with myself and [producer] BloodPop, and just made a full body of work. So I wasn’t chasing my tail, but it’s been almost a decade of chasing my tail.

So what was the sonic approach of the discarded album that had “Hero” on it?

There was no sonic approach. It was just all over the place. It was a lot of consideration of other people: “I hope people like this.…” I had a collection of songs that sounded good, but were missing the gut punch.… I remember Max Martin called me and said in his very soft tone, “Do you know what I miss from a Charlie Puth record? I’m missing some of the emotion lately.” And I thought to myself, “Oh, my God, how could I let myself get to this point of where I feel like I have to be on a song conveyor belt and have to get things done for the sake of getting things done?”

Did the Taylor mention in fact put a bit of a fire under you to live up to the shout-out?

I understood exactly what she meant, I think. To be a bigger artist, I think you have to let people in a little bit more, and I hadn’t let people in as much as I should have in the beginnings of my career. It was more about making sure that people were happy.

The first song you wrote for the album was “I Used to Be Cringe.” How did it come to you?

I remember it was my wife Brooke’s birthday. I was on my way to this wonderful restaurant in Sherman Oaks, and these songs will just pop into my head. And I heard this lyric called “I Used to Be Cringe.” And the title itself is cringey. It’s like, “What do you mean?” You can smell the comments, as they say — “Used to be?” I’m like, “That’s an interesting song title. What would that sound like?” And I’m just talking to myself while Brooke’s on her phone. It’s like a 30-minute drive down the hill, and I just start writing this whole song in F major. And it has a very flowy McCartney-esque chord progression. And it’s all just because Taylor had said something about me. It gave me enough excitement to write another song in my head. And now we’re ending the album with that.

It raises the question — when, in your opinion, were you the most cringe?

I think when I dyed my hair blond just to get reactions — that’s literally a lyric in the song. Saying things in interviews that weren’t true, because I was told by higher-ups that I’m a white guy with brown hair. Literally, they said I need some excitement around my project. We need drama. And I didn’t know what it meant to be an artist. I started out writing music for other artists. So I made tons of mistakes along the way. The blond hair was really bad. I don’t know what I was thinking there.

“I Got what taylor meant: To be a bigger artist, you have to let people in.”

You had a lip ring at one point.

Yeah, man. It wasn’t real either. I would talk differently in 2016. I would go to a radio show and tell myself, “You’re gonna put on a cool-guy accent because you have a big song out right now.” It was just so much inauthenticity.… I thought I had to be a certain way to be popular. And again, it’s part of, I think, a young man growing up and not knowing himself and being very influenced by those around him. Comments that the higher-ups at the record label or former management would make were sometimes right. So if they’re right about that, they must be right about making up a bullshit story, because it’ll make the song more exciting. None of that was who I am. I can’t even look at myself half the time from the years 2015 to 2022. I just didn’t know what I was doing. I used to be very cringe.

At some point you realized you’re not gonna try to be some super-cool version of yourself.

Yeah. It’s never gonna happen.

When did you have the realization that you were gonna drop all of the pretending?

I think when Brooke became a serious part of my life, it was weird to do that in front of her because it’s someone I’ve known all my life. I never did it in front of my mom because my mom knows me so well. I’m not gonna do it in front of Brooke because Brooke’s going to look at me like, “Who am I dating right now?” It stopped then. And then I really just think the male frontal lobe doesn’t develop as quick. I really think scientifically it’s that. It just took me a while to grow up.

Brooke is someone you’ve known since you were a kid. Marrying her, rather than someone from the showbiz world, says a lot about the life you’ve decided to have.

I’ve always wanted that life that you speak of. I knew very early on that it was Brooke, as well. Again, frontal lobe not developed. Twenty-four-year-old kid thinking to myself I need to enjoy the fruits of my labor: “I deserve all of this.” I’m very thankful for every experience, but I always knew what was best for me. I just pushed it away.

Looking back at a song like “LA Girls,” from 2018, there was a lot of ambivalence about whether that was the world you wanted to be playing in.

I thought to myself as a young kid that I had to be in constant turmoil in my life in order to write great music. Couldn’t be furthest from the truth. It’s when I was most comfortable and happy is when I wrote my best music. I don’t know where this came from, where I had to … I don’t know if that was people giving me bad advice. I think that was my own doing. My life had to be in constant disarray to come up with melodies, and so I resisted settling down for such a long time.

So when you got married, did you have that lingering fear of “I’m happy — this is gonna screw everything up”?

No, I just chemically knew that it was the right thing to do. It made me not wanna look at past interviews of myself anymore, but I knew I made the right decision. I feel back to how I felt before I became a singer.

Photograph by SACHA LECCA

Was there a moment when this actually clicked in or was it more gradual?

I was in New York, I was staying at the Greenwich, and I don’t drink at all. I think it clouds my judgment. But it was right before the third album was about to come out, and I was like, “I’m just gonna have a rager.” And I woke up with the worst hangover I’ve ever felt in my life. It lasted for, I think, two days. And I saw pictures of myself with people I didn’t even know. And I remember they all wanted to get coffee the next morning, in a scene-y part of town. I saw them all eating, and then I just turned the other way and walked back to the hotel and just stayed there by myself for a couple days. It’s hard to describe, but after years of surrounding myself with the wrong things and saying the wrong things, it’s profound when it just all comes to a screeching halt one day at 30 years old in New York City.

The song “Cry” is about your dad, and features Kenny G on saxophone. How did that come together?

Me and BloodPop looked at each other while we were making that song and thought we need to put Kenny G on this, because it just felt like Sade, it felt like 1988. I texted him, and he sent [a solo] back right away because he was like, “I just love the record so much.”

But I wrote “Cry” for my dad, and I really resisted [doing] that. BloodPop has a very unique way of making me feel uncomfortable yet comfortable. The first day he came in with a big whiteboard and said, “OK, we’re gonna have some really tough conversations.” And I started getting acid reflux, and he was like, “Why haven’t you written a song about your dad?” I got defensive: “I don’t want to talk about my dad. I just wanna collaborate with you and make bops” is what I legitimately said to him. And he was like, “Your dad’s gonna want a song one day.”

Then a week later, [my dad’s] mom passed away. The song’s basically about not being afraid to show emotion. It’s like Blood predicted the future. And as we were at the funeral, I thought to myself that we gotta finish that because, turns out, he does need it.

“I thought i had to be in constant turmoil to write great music. couldn’t be less true.”

There’s also a full-on yacht-rock song on this album written with Michael McDonald and Kenny Loggins. What did you take away from the experience of working with them?

That I’m not alone. That there are musicians that have been doing it for much longer than I, that have a very similar approach to chords and implementing jazz into pop music. And I slapped myself on the head. I’m like, “Of course! You got all that stuff from the two legends that are sitting on your couch writing the song with you right now.” Michael McDonald writes music like a hit songwriter of today. He has the same approach as Amy Allen. And it just reminds me that all music really is the same.

You’re doing the national anthem at the Super Bowl in February.

The hardest song ever written.

Photograph by ELIZABETH WEINBERG

And for some reason, Whitney Houston was brought into the conversation, and now you have to match the Whitney Houston performance?

Because of New Jersey. She’s from Newark. And I would be the second New Jersey native, as The Star-Ledger wrote, to sing the national anthem. It’s a great honor. I’m going to be inspired by what Whitney did, but I can’t ever touch what she did. That’s the best one ever done — that and the Chris Stapleton one. That was raw. Made grown men cry. I just want to do my own thing with the hardest piece of music ever written. And I just wanna show people that I can do it. I feel like people don’t really think of me as, like, a stand-alone vocalist at times…. I actually have always wanted to do this, and I recorded a little demo, just me singing with the Rhodes and sent it to Roc Nation. I’ve been told Jay-Z loved it, and it got to [NFL Commissioner Roger] Goodell and they all said that I could do it.

So you applied for the gig?

I applied. I auditioned for it, but I made up my own audition because I’ve always wanted to do it — because I love it musically. It’s the best song. Musically, it’s so special.

The rumor has it they prerecord that because of the cold.

They’ll prerecord bits of it. It’s impossible to mic an orchestra and expect that it’s gonna sound good in a stadium that’s filled with a hundred thousand people that are going to be cheering.

But for you yourself—

I’ll be singing. The mic will be on.

You’ve said that you had a certain amount of insecurity with your voice, and you perhaps compensated by using Auto-Tune too much in the past.

Oh, yeah. Third album, I tuned my voice way too much. I just wanted people to like my music so much. And if I went off tune, I felt like that would piss people off or it would make them mad, and I want them to be happy. It’s a very outdated way of thinking. And something that I speak out against a lot now. I’d always tell aspiring songwriters and artists to embrace the imperfections.

Those concerns in your head about people being mad at you and stuff like that seem, frankly, more like psychological issues.

I’m sure I’ll need years of therapy. I always think people are mad at me. I’m always afraid of disappointing people, and I don’t feel like that’s ever gonna go away.

When you wrote your breakthrough hit, “See You Again,” you were in a mode of writing for other people. You never thought you would sing the hook — people like Sam Smith were supposed to.

And then I think Skylar Grey sang the hook, and I think Jason Derulo sang the hook. Chris Brown sang the hook. Suddenly all these A-list artists wanting to sing your song — it happened overnight for me. I had all this attention from all these record labels overnight, saying crazy things to me. That song was written because my friend who had passed two years prior always told me I would write that song. So I wrote it for him. And what’s great is that people who were born 10 years ago are listening to it today, and it feels like a brand-new song for them. It’s the gift that keeps on giving. It’s the power of music.

“I wrote ‘cry’ for my dad. I resisted it, but it Turned out he needed it.”

People may not realize that the song really owes a lot to Bruce Springsteen. It has that chord progression that he used in “My City of Ruins” — and also the mournful approach to the lyrics seems inspired by The Rising in general, which I know was your first Bruce album.

The reason why it was my first Bruce album was because my town that I lived in was a Wall Street sleeper town, and there were a lot of people who lost their lives in 9/11. He wrote that record pretty quickly. I remember going to Jack’s Music Shoppe in Red Bank, New Jersey, and picking it up and hearing it and just being so blown away. I felt like he wrote something for me personally. And my friends who actually lost their moms and dads, they felt the same way. I felt close to him and like it was the first time I ever felt that with any artist.

You’re an artist pondering one of the big questions right now, which is how the infinite supply of AI music will affect real music. One thought is maybe it makes artists aim to be more human, more weird, more individual.

That’s what I did on this album. I had to lean into the human aspect. The vocals couldn’t be tuned like they were on my last project. Not everything can be so perfect. It makes it feel like a human made it. That’s also something BloodPop wanted me to lean into. He was like, “How many times can you sing about a relationship from seven, eight years ago? It’s all starting to sound the same. Sing songs about family. You’ve never sung about that.” I think there’s gonna be such a wave of all this artificial stuff, but it’s gonna make the human stuff stand out even more. I refuse to believe an AI engine will make me cry the way I do when I hear a song like “I Can’t Make You Love Me.”

You have a big year ahead — both your baby and your album are due in March, and then touring. It’s tough to tour with a new baby.

I honestly can’t even think about it right now because that’s why my jaw tenses up. I always want to make sure that I’m there for baby. I wanna make sure that the baby has a normal life, and we’ll have the big headphones onstage, behind stage, and hopefully I can wave to baby.

So they’re coming with you?

Not for everything. Because touring is a really unnatural thing. And I can just tell that’s not gonna be sustainable. So we’ll do it where it makes sense, but I just want the most normal life for my child possible. I don’t want them to travel on airplanes constantly.

This album is probably the biggest pivot of your career. Do you see it as establishing a direction where you’re gonna go forward, or do you want to leave it open?

I think sonically, musically, things may change and pivot, but what remains the same is the nucleus of it. I’m always gonna remain myself and tell the truth from now on.

What does that mean?

It means I’m not gonna embellish things anymore and be so concerned if people are gonna like me. Of course, I’m gonna always care about what my fans think and what people think of my music. I wouldn’t be human if I didn’t. But I’m not gonna let that consume my life so much that it makes me write music that I end up scrapping ’cause I was just so concerned about what people thought. I’m always just gonna remain true to myself, which is the most lame thing to say ever. But it’s true. I’m gonna be me. Because that ended up being the coolest thing.