Fifty-something years after Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Billy Joe Shaver, Tompall Glaser Jerry Jeff Walker and a whole host of others set up the framework for outlaw country, the movement is alive and well in a new batch of free-thinking, system-bucking alt-country greats.

Most of the living original outlaws have moved into legacy status, but a few, such as Steve Earle, are still working touring artists.

Joining them is a younger set consisting of Margo Price, Elizabeth Cook, Jason Isbell, Sturgill Simpson and a slew of others often pointed to as heirs of the outlaw movement.

Read More: 30 Songs That Define the Outlaw Country Movement

But what’s changed about outlaw country today? What does an outlaw country singer sing about? Has the rebellion itself changed since the ’70s? Has the status quo changed?

And are these outlaws pushing back solely against the artistic confines of mainstream country music, or something bigger?

Well…it depends on who you ask.

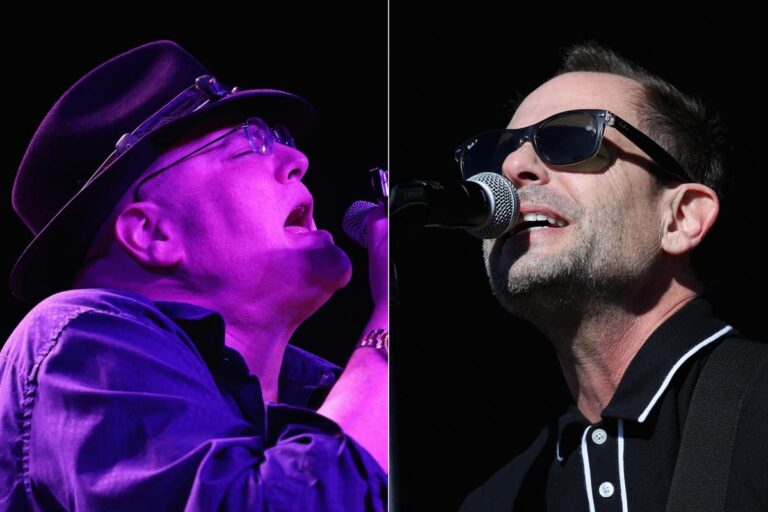

I spoke to three working artists from three different touch points and eras of the subgenre — Dale Watson, Ray Wylie Hubbard and Cross Canadian Ragweed’s Cody Canada.

Each defined outlaw country as a form of independence: An artist’s side-stepping of Nashville’s old guard in order to make their music, their way. All three have deep ties to Texas and the Austin outlaw scene that’s been a hotbed over the past half century.

Is Outlaw Country About Flying the Flag For Roots Music, Or Pushing the Genre Somewhere New?

Most people, when they think about outlaw country, think about that first wave of artists in the ’70s. That musical style is ingrained in most of the subgenre’s heirs.

“It was part of our DNA as far as my music,” says Dale Watson. He’s been tied to the Austin alt-country scene for his whole career, and the city is also home to his Ameripolitan Awards, a yearly show since 2014 to spotlight outlaw, honky tonk, Western swing and rockabilly music.

Jacob Blickenstaff

Today, Watson’s music sounds like a time capsule from another era. “It’s just more rooted,” he acknowledges. “That’s the way my stuff is.”

His new single “Waylon, Willie & Whiskey” — the first off his upcoming Unwanted album — is no exception. The single arrives on Jan. 23, but you can get an early listen at a live video of the song below, exclusively for Taste of Country.

Watson says he wrote the song in real time onstage after spotting a fan in the front row who had the title phrase written on his shirt. “I knew by the time we got around to the chorus the second time, when everybody was singing it, that it’d probably be a song I’d keep doing,” he recounts.

In an era of genre-bending, experimental country music, traditionalism does feel like rebellion to Watson. “There’s a quote by Marty Stuart I lean on that say, ‘The most outlaw thing you can do nowadays is play country music,” he says.

But Watson doesn’t believe that’s the definition of outlaw country.

“The reason they call it outlaw country is because they were doing what they wanted to do without permission. Without regard to what the record label wanted,” he said. “That’s the one thing that’s been a constant in all of it, you know, from Billy Joe Shaver…down to people like Nikki Lane.”

Has the Importance of Songwriting Changed in Outlaw Country?

The image of the outlaw singer as a troubadour is an important piece of the movement’s legacy, but historically, it’s been pretty common for outlaws to record songs they didn’t write.

Shaver wrote most of Jennings’ Honky Tonk Heroes album. Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson covered each other all the time. And Johnny Cash cut songs written by Shel Silverstein.

I asked Watson if he thought writing and recording your own songs has become more of a rebellion as mainstream Nashville streamlined the songwriter’s room, placing full-time songwriters together for sessions to crank out as many radio hits for as many stars as possible.

He responded that around 1992, he spent about 10 months writing for a publishing company, and one day, he was booked for a session with two other writers. Before he got there, they’d been looking at a pitch sheet: A list of artists currently recording for albums, and the type of songs they were looking to cut.

“They wanted to write a song for Wynonna Judd, and she was looking for an ‘edgy power ballad a la Melissa Manchester meets Bonnie Raitt.’ It was that specific. And they were like, ‘We’ve kinda got the idea, we’re gonna go with, there’s this teenage girl and she’s pregnant.'”

“I was like, ‘I’m out,'” Watson remembers. “That’s when I let myself out of the Nashville songwriting machine.”

By contrast, in the outlaw subgenre, cutting someone else’s songs was often more about friendship, serendipity or simply being a fan of the person who recorded it first.

Cross Canadian Ragweed frontman Cody Canada told me that in the ’90s, when his band was coming up, they often covered Steve Earle.

Earle’s Guitar Town album was formative for Canada as a young fan, especially because he heard his own father’s struggles echoed in the lyrics, about addiction and coming of age during the Vietnam War.

Michael Buckner, Getty Images

But some fans didn’t catch that Ragweed’s versions were covers, and maybe didn’t even know who Earle was at all. “And then the next thing you know, [that fan]’s like, ‘Man, I bought a couple of [Steve Earle] records and I love it.”

“It just felt like the outlaw movement, everybody was really helping each other out,” Canada continues.

The Outlaw Country Community Takes Care of Each Other

And all three, at some point during our interview, rattled off a list of lesser-known acts I just had to check out, people they’d worked with or seen at small venues.

“That’s my favorite part about it…it’s more of a community than the mainstream stuff,” Canada reflects, pointing out that outlaw artists might not have a publicity team or a major label promoting them the same way a mainstream star would.

Instead, they rely on each other — and their ability to build a fan base listener by listener, show by show — to keep their careers alive.

Fan bases are tight communities, too; there’s a strong bond that comes along with being fans of the same lesser-known artist. Canada remembers a “deathly hot” show that Ragweed once played in Waco, Texas, where he looked out from the stage and saw how “everyone was taking care of each other.”

“It was good to witness,” he says. “I felt like we had the best seat in the house.”

He also mentioned another show, when one concertgoer with “a certain colored hat on” was “just trying to be an a–hole to people.”

“There’s 40,000 people having a good time and he’s just not going to have it,” Canada describes. “And I watched all these people not raise a fist, not raise their voice…just scoot in and politely push him to the back barricade. He had to leave the pit. But they did it without violence.”

“And that’s our fan base,” he adds.

Is Outlaw Country More Political Today Than It Was in the 1970s?

In case you didn’t catch the “certain colored hat” comment, Canada says he and most of the artists he runs with are “liberal dudes and ladies.” Especially over the past decade, he’s noticed more and more of his cohorts either writing more political songs or “just having a hard time being quiet.”

He thinks that having the freedom to vocalize your views, without getting muzzled by a diplomatic record label, goes hand in hand with outlaw country’s history.

Dale Watson isn’t so sure.

“The original outlaw thing wasn’t about that,” he said, when I asked him if freedom to share political views was part of the creative freedom that Jennings, Shaver, Kristofferson and Nelson were seeking back in the day.

“Waylon didn’t go that way. Johnny [Cash] did in a very classy way. So, I think, did Willie…he’s not out there saying, ‘If you don’t vote this way, you’re a horrible person.’ But a lot of people are doing that,” Watson continues. “I think it’s sad when you have to — you’re a musician, just do the music, you know?”

He pointed to the merging of outlaw country and folk as the point when outlaw music got political. Ray Wylie Hubbard also told me that political viewpoints were connected to different genres: He said that rednecks and hippies listened to either country or rock, respectively, and for a while, you couldn’t cross that genre line.

Terry Wyatt, Getty Images

But Hubbard thinks that there’s always been a political context for the outlaw country movement. “Yeah, of course,” he said, when I asked if the cultural tensions of the ’70s informed the first wave of the movement.

“The country was really kind of torn apart because of the Vietnam War and civil rights and women’s rights, and all of the sudden the Beatles come in, and the Stones had long hair, and if you had long hair, you were anti-establishment,” he detailed. “It was a very turbulent time.”

Read More: The Top 20 Waylon Jennings Songs

Hubbard (who, it should be noted, has had long hair for most of his career) wrote his outlaw classic “Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother” — a song most famously recorded by Jerry Jeff Walker — after “almost getting beat up” at a bar in New Mexico in the early ’70s.

It was a sort of response to Merle Haggard’s “Okie From Muskogee,” a song that was “kind of a diss on the whole long-haired hippie from Austin thing,” Hubbard says. “So ‘Redneck Mother’ was kind of an answer to that, like, ‘Hey, your mom raised a redneck.'”

It might’ve been a turbulent, “us versus them” time, but the two sides could find common ground through music. Haggard gave “Redneck Mother” his blessing and even insisted that Hubbard play the song while opening for him one night, and came out to the side of the stage to watch with “a big ol’ smile on his face.”

There was one artist who could always get the hippies and the rednecks to stop fighting and come together, Hubbard continues, and it was Willie Nelson.

Read More: The Most Politically Outspoken Country Stars

“You’d see these old guys in cowboy hats, they’d been out on a tractor, and they’re standing next to some hippie guy that had been in the parking lot smoking pot, and they’re together because the music is so strong,” Hubbard continues, speaking about watching Nelson play at Armadillo World Headquarters.

Robert Mora, Getty Images

“Boy, the music, that was the key. That was the catalyst,” he adds. “That was the thing that put everything in the pot and threw it together and you had gumbo.”

Is there an artist today who can bring crowds together like that? Hubbard can’t think of one.

“It’s us or them. You’re either gonna be for Kid Rock or the Chicks. You aren’t gonna be for both, even if the music’s good, because of that political divide. It’d be very hard to find an artist I know that can do that,” he says.

Then, he drily joked, “Except me.”

The divide may be bleak, but all three of the outlaws I spoke to for this story had reasons to feel optimistic about the future of the movement, too.

What’s the Future of Outlaw Country?

Hayes Carll, Blackberry Smoke and Whiskey Myers are just a few of the acts brought up as new champions of the outlaw subgenre, a movement rife with fiery young guns and alt-country stars more than capable of carrying it forward.

Cody Canada sees hope in his fan base, as vibrant and dedicated to packing out venues today as it was in the ’90s. Incredibly, Cross Canadian Ragweed hasn’t lost all that much fan momentum even after a two-decade break.

And Ray Wylie Hubbard points to the inspiration he’s found in Nashville’s outlaw-leaning mainstream acts such as Eric Church, with whom he co-wrote “Desperate Man” in 2018.

He’s also found reason to be hopeful in the songwriter’s rooms, for all their commercialization.

After his co-writing experience with Church, around 2019, Hubbard says he agreed to a co-writing appointment with another artist — this time a young woman he’d never met before.

“All of the sudden this young girl comes in and says, ‘Hi, I’m Lainey Wilson,'” Hubbard recounts. “Never met her, no idea who she was…So we got together and wrote this really bada– song, and six months later, she’s everywhere.”

“I hope she has retained that — because she just came in with this attitude of, ‘Let’s write this song and make it cool and make sure it works,’ you know what I mean?” he goes on to say.

At its heart, outlaw country has always been about protecting the integrity and authenticity of the song. In 2026, musical authenticity is not in short supply. And with the original outlaws’ legacy still looming large and bleeding into mainstream country, a modern-day outlaw sensibility can pop up anywhere. You just have to know how to recognize it.

The Top 20 Waylon Jennings Songs

Waylon Jennings’ 20 best songs show why he’s among the largest-looming figures of the outlaw country movement. But they also prove his versatility.

Jennings’ discography includes some ambitious covers of songs that were already massive hits — and without exception, his versions could stand toe-to-toe with the originals. It also features some lesser-known cult classics and a tender love ballad or two.

Keep reading to hear the songs that prove that country music wouldn’t be country music without Jennings’ incredible influence.

Gallery Credit: Carena Liptak