W

ithin minutes of arriving at the studio for their Musicians on Musicians shoot, Redman and Black Thought are exchanging daps and catching up like old friends — because they are. The two voluble MCs, who took parallel paths to fame in the Nineties, laugh and swap stories in the dressing room while the cameras are getting positioned a few feet away. When it’s time for the filmed conversation to start, they simply walk over to the set and keep talking — about how they’ve inspired each other to step up their lyrical techniques; about close friends gone too soon; about how much they’ve enjoyed their recent collaborations at Roots Picnic events in L.A. and Philadelphia. Redman, 55, is feeling creatively energized after the 2024 release of Muddy Waters Too, a sequel to his classic 1996 album, Muddy Waters, and Black Thought, 52, shares that the Roots are almost done with their first album since 2014. When they reach the end of the time allotted for this conversation, nearly two hours after it starts, these microphone masters don’t want to stop. “One more question!” Redman insists. “We want to do another hour,” Black Thought adds, with a laugh.

Redman: When did our paths first cross? I know my path started from the Roots album [1996’s Illadelph Halflife]. You all was in my CD player. You all was part of my growth of dopeness and the caliber of how I should be spitting — especially you, bro, especially songs like “[Concerto of the] Desperado.” You held the high bar of what an MC should be.

Black Thought: Wow. Me and Malik [B], who, rest in peace, was the other MC earlier on in the Roots — in college, all we used to listen to was your shit! I had a suspicion that you were a Roots fan. But when you dropped that line, “I love to burn to the roots” [on LL Cool J’s 1997 song “4, 3, 2, 1”], that was it. “I told you! You heard, he said it!” That was validating for me as an MC, and for the Roots. Because when we came out, we had the live instrumentation, but we had to approximate the sample sound. We were always concerned about how that was going to be received. I felt like me and Malik almost had to rap harder. We had to overcompensate as writers, as lyricists, as performers to make folks comfortable with the fact that we were playing with a big upright bass.

Redman: I can honestly say, bro, on the Muddy Waters album, when me and [Method Man] did this song called “Do What Ya Feel,” that whole round was inspired from you. If you listen to it, you’ll hear how I caught your flow a little bit. Especially then, I was deep in the Roots. Every time I go overseas, Roots is my first CD I’m popping in for that excitement, for that hype I need to get before stage.

Black Thought: That means so much, bro. [Questlove] is going to lose it when I tell him.

Watch the video interview below

Redman: Plus, I always admire it, too, like, “How the fuck do you remember all these rhymes, bro?” Your brain is crazy! I got to spend two months with the headphones on in the gym trying to go over songs and remember them. You, bro, when you do the Picnic or the show we just did out in L.A. — the rhymes onstage, you wasn’t even using the prompter. It was there, but you wasn’t even using it. I’m like, “Damn, man, how the fuck he writing rhymes to our beat?”

Black Thought: I think there’s something to be said about the level of professionalism that MCs from our graduating class have in our flexibility, the way that we keep it malleable. We expect to have to improvise.… I’m a little bit younger than you. I was born in ’73 in October, a couple months after they say hip-hop came along after the party up at Sedgwick [Avenue in the Bronx]. You were three or four years old, though, right? Do you remember as a young person what it felt like when hip-hop came? I have no memories of a time when it didn’t exist.

Redman: Yeah, it was Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. When I first heard “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash,” I was like, “Wow, what is this?” And then it moved on to Run-D.M.C. When I first seen them — not just heard them, but when I seen them with the black leather and the Adidas — I was like, “I got to be a part of this music.” It was something that changed my life, meaning I don’t care about the money, I don’t care about the fame, I just want to do this the rest of my life, for the love of it.… Who was your inspiration artist that helped mold you?

Black Thought: My top five … Who’s at the top is ever-changing, but Kool G Rap, Big Daddy Kane, KRS-One, Rakim, Run-D.M.C. on any given day. You talk about representation. When I was a young person, seeing people like LL Cool J, Special Ed, MC Lyte — it spoke to the power of youthful expression and how dope the young creative mind was. I was always looking for some resemblance of myself in the arts, and I got it from hip-hop during that period.

Redman: That’s right.

Black Thought: Man, Biz Markie blew my mind playing a joint one time. He was like, “Yo, you aren’t up on this.” It was you and Biz freestyling at a park in Queens. That was a crazy freestyle!

Redman: Rest in peace, my big bro. Shout-out to Biz. He lived in downtown Newark. He allowed me to pull up on him at his crib, go through records. He was like, “Roll with me.” At the time, I was in the streets making money. I had to make a choice.

Black Thought: Yeah. That often is the case.

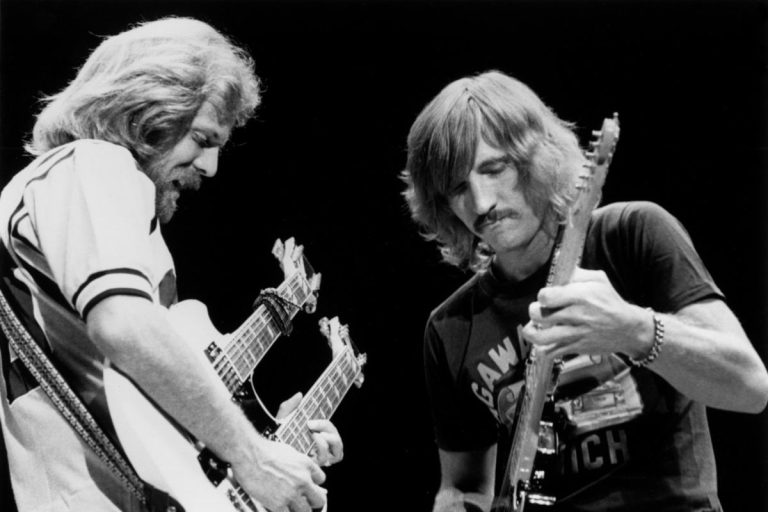

Black Thought (left) and Redman in New York, June 2025

Redman: I made the choice of going full-fledged in the music, but my pockets was a little empty, so I still had to hustle a little bit. Biz took me around battling for money. I was up in New York airing motherfuckers out, bro, for some change. That park in Queens was supposed to be a battle, and they were going to tape it, and the dude didn’t show up. Biz was like, “All right. Before we get out of here, we’re just going to kick some bars.” After that freestyle, Stretch and Bobbito picked it up on their radio show, and then Sway and Tech picked it up on their show out there in L.A. They was like, “Yo, who is this dude?” I got to give a lot of credit to Biz.

Black Thought: He understood mentorship. If you were dope, if he saw a level of brilliance in you as a DJ, producer, MC, he was going to try and encourage that.

Redman: Are any of your kids in hip-hop or doing bars?

Black Thought: My youngest son, who’s only 10, seems to be the most musical. My oldest son, who’s 25, he went to college for music. He’s got a degree in theory. But do he got bars? I got five sons and a daughter. Only two of them seem like they’re even leaning toward music. I try not to impress it upon them, so they can figure it out.

“MCs from our graduating class… We keep it malleable. We expect to have to improvise.”

Black Thought

Redman: None of my kids want to do music. My daughter goes to school right here in Manhattan. She wants to do more acting and behind-the-camera stuff, and I admire that, because she got character, like me.

Black Thought: Oh, nice.

Redman: But none of them want to do rap. I’m like, “OK, I’m fine with that.” [Laughs.]

Black Thought: How about your skydiving hobby? Have your kids done that with you?

Redman: No.

Black Thought

Black Thought: Who’s like, “OK, cool, I’ll go skydiving with you”? Has Meth done it with you?

Redman: No, no.… I reached out to Snoop. He’s like, “Yo, I got to think about that, cuz.” Meth just said, “No, I’m not doing that.” What I love about it is that when you’re in the air, there’s no judgment. There’s no racial standards in the air. Once you get in that plane and you got your parachute on and you’re ready to dive, it don’t matter if you’re Black, white, poor, or rich. This is not a sport that you can throw money at and be like, “Yo, I’m going to kill it because of my team.” None of that shit matters when you’re on that plane and ready to jump. That’s one of the reasons I don’t smoke no more — you always have to be disciplined when you’re skydiving. I tell anyone, if you want to challenge yourself, come take a skydive and feel what I feel.

Black Thought: Which is beautiful. Get out of your comfort zone.

Redman: When are you going to do it, bro?

Black Thought: Oh, man. [Laughs.]I was hoping that you didn’t think I was asking.

Redman: Well, I’m asking. I will lay out the red carpet for you, bro.

Black Thought: What’s it like in the sky when you’re falling down?

Redman: You’re falling, like, 100-something miles per hour. You have to arch your body, hands up, and that’s how you get balanced. You always gotta check your altitude awareness and make sure you know when you’re pulling your parachute. I’ve had seven malfunctions, where it was a 50/50 chance if I would live or not.

“Once you get in that plane and you’re ready to dive, it don’t matter if you’re Black, white, poor, or rich.”

Redman

Black Thought: Whoa. What?!

Redman: Yeah. But I followed my procedures, and I didn’t panic. I had a line twist. When you’re spinning that fast in the air going down, your first thing to do is panic, but I didn’t. I actually fixed it. When I landed, my instructor — shout-out to Pedro, shout-out to Space Skydive in Texas — he was like, “Yo, you’re an official skydiver.” I think you should try it, bro. I’m not going to pressure you on camera, but it’s something to look into.

Black Thought: Me and Jimmy Fallon went to Puerto Rico, and we did this zip line. At the time, it was the highest, longest zip line, called the Beast. That’s the closest I’ve ever come, I guess, to skydiving. You’re laying flat and your legs are out. It was an adrenaline rush that I didn’t think I was going to love, but I loved it.

Redman: How did you guys land the Jimmy Fallon gig? Yo, I remember the day he announced that. He said, “The Roots will be my band.” … When you guys got that job, it was a win for our culture, honestly. We looked at you all and we applauded. It was a win for hip-hop.

Redman

Black Thought: Shout-out to Jimmy Fallon. Man, the way we got the gig, Jimmy was always a huge music nerd. He’s a huge, huge Beastie Boys fan. That’s the first band that took the Roots on tour. We learned the ropes from them. When everything changed in ’07, ’08, [after] Napster hit and the way people were receiving their music changed, Jimmy came around and said, “I’m thinking about doing the Late Night show, and I need a band. Would you guys be interested in doing it?” We thought it was bullshit until he kept coming around.

Redman: You didn’t grasp it the first time he asked?

Black Thought: Not at all. It was a year and some change. We would show up at a gig, and he’d be in our dressing room, like, “Hey, hey, what’s up? I was serious about what we talked about.” He was dedicated. He showed up a bunch of times pitching it. This was around the time that we had just got done working on Dave Chappelle’s show. It was so much uncertainty at that time that it sounded good to have a day job. But we didn’t want it to mean the end of the Roots.

Redman: For Red and Meth, we did the movie How High. You know how it is in hip-hop. Once you get on that screen, people are like, “Oh, he isn’t bodying the mic no more.” We were blessed that people still accepted us as those underground dudes that still got bars. Did anything like that happen to the Roots?

Black Thought: It was a concern. What we wound up doing was just to lean into the seriousness, the gravitas of the music that much more. So if you listen to the Roots albums from [2010’s] How I Got Over, the last three or four Roots records, they get progressively shorter, but more densely packed and more conceptual.

Redman: Mm-hmm. I always looked at you like, “This guy has his life together.” When people think of Black Thought, it’s always controlled. It’s “You would never see me sweat.” And I know that’s a part of healing, because that’s the level I’m on now — self-healing, self-awareness, self-love. How important is that?

Black Thought: It is of utmost importance. Rich Nichols, who was the Roots’ longtime manager — he was my entrée into the space of spirituality, meditation, veganism, all that stuff. I was a young person when he came into my life, and he came at a time when I really needed that guidance and discipline. I met Rich two or three years after I lost my mom. I lost my father at a super-young age, one or two. And then my mom passed away when I was in high school. We were already the Roots, Quest and I. And Rich came along and filled the void. He changed our lives.

Redman: I want to tell young artists to learn more about themselves. I follow these three words: transparency, accountability, and vulnerability. If you don’t know what it means, you should look it up. Once I started following those words, it changed my life. I’m just now learning more of what self-love is. Because I’m a hip-hop baby — I’ve been on tour since 19 years old, bro, so it’s been a fast life for me all those years. The only way we can make a change is if we change ourself.… I asked you that because you’ve always been a gentleman that I respected, besides the music. You always carried yourself as a man of integrity and intelligence.

Black Thought: I appreciate that, bro. It’s emotional intelligence that we strive for. It is never easy, right?

Redman: You know what? This was something I needed from you. I appreciate you building with me.

Black Thought: Thank you, brother. This is a dream come true for me.

Production Credits

Photographic assistance PAULA ANDREA AGUDELO and SEAN MANUEL. Digital Technician ISAN MONFORT. Video Director of Photography WILL CHILTON. Camera operators HALEY SNYDER, SOPHIE POWER, ALEX CANTATORE. Editor GRAHAM MOONEY. Audio engineer GABE QUIROGA. VFX MIGUEL FERNANDES

Location HUDSON YARDS LOFT