A

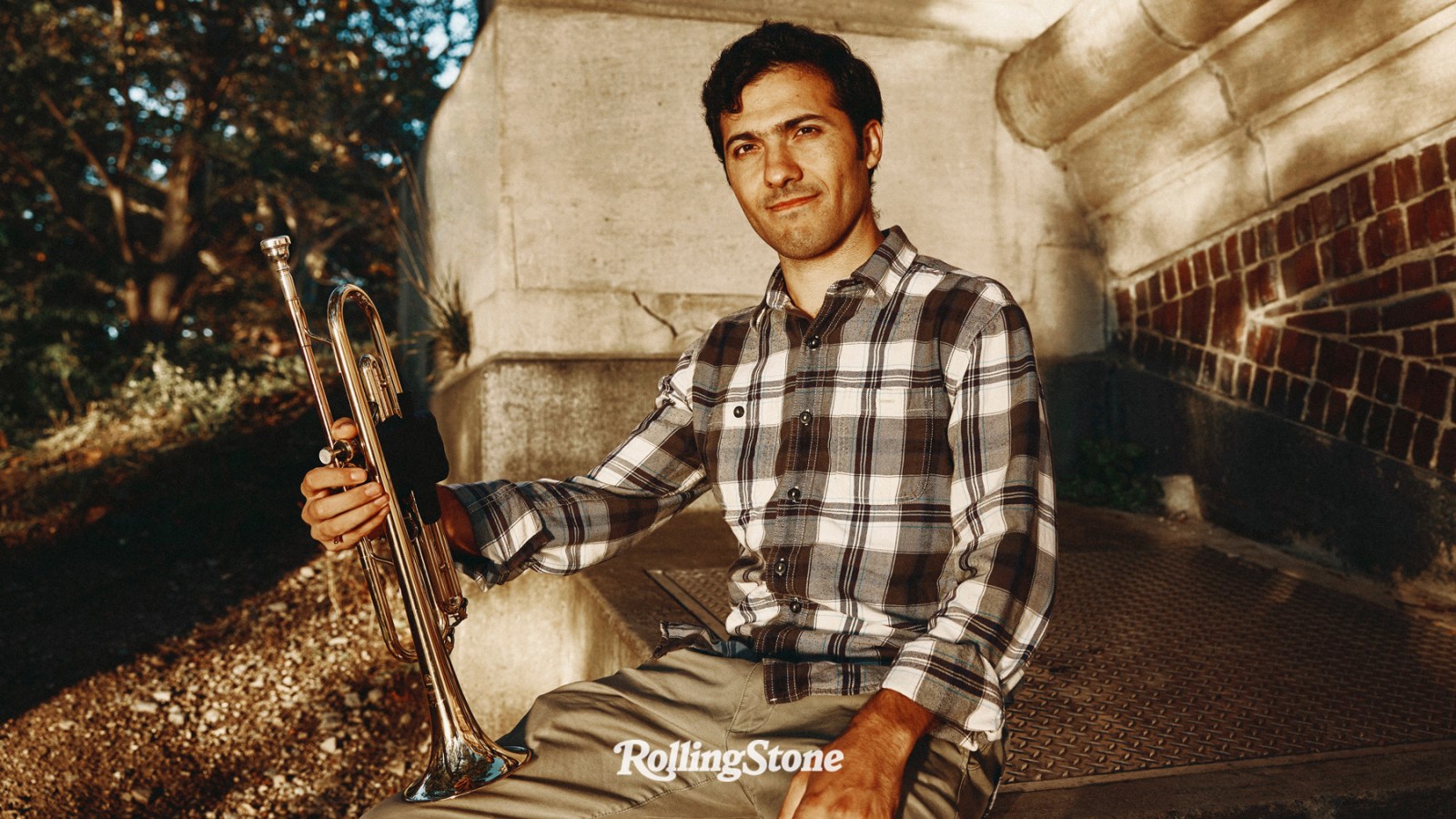

s the Taliban entered Kabul, Afghanistan, on Aug. 15, 2021, Qudrat Wasefi, a resolute 22-year-old trumpeter, flung open the windows of his music school’s empty wood-paneled studio and started to play as loudly as he could.

“I thought it was my last time,” he tells me, crammed into a booth at a taqueria in Cambridge, Massachusetts, while Harvard Square’s lunch rush is at full tilt. Beside him sit Bob Jordon and Derek Beckvold, two Americans who once taught him scales in Kabul and understood the stakes: Under the Taliban, music — especially from the West — was illegal, punishable by beatings, imprisonment, or death.

The day of the invasion had been thick with heat, the kind that made the air above the sidewalk kebab spits ripple with diesel smoke. Wasefi was guiding members of Afghanistan‘s first all-female ensemble through a recording of their compositions.

Mid-song, the doors flew open. Their instruments rattled and their voices faltered into soft silence. A bus driver walked through the center of the room and called Wasefi to the corner, his face drawn tight.

“The Taliban are here,” he said quietly. “I need to drive everyone home.”

Even as the Taliban had toppled one province after another, no one had believed that they’d make it to Kabul — especially not the members of Qudrat’s Western music school, to whom the Taliban posed a dire threat. A line of cars stretched down the street: the first tremors of the panic that quickly spread through the city’s bones.

“Why should we leave?” Wasefi asked, anger rising in his chest. “Why are you scared?”

“You have never seen the Taliban, son,” the driver said. “I have.” The girls packed their bags and went home. The classroom stood empty.

That day, 3,000 miles away, Jordon and Beckvold were refreshing WhatsApp obsessively. The drummer and saxophonist had left Kabul years earlier but stayed in touch with their Afghan students through the app, occasionally helping with visa applications. Now those casual connections had become lifelines.

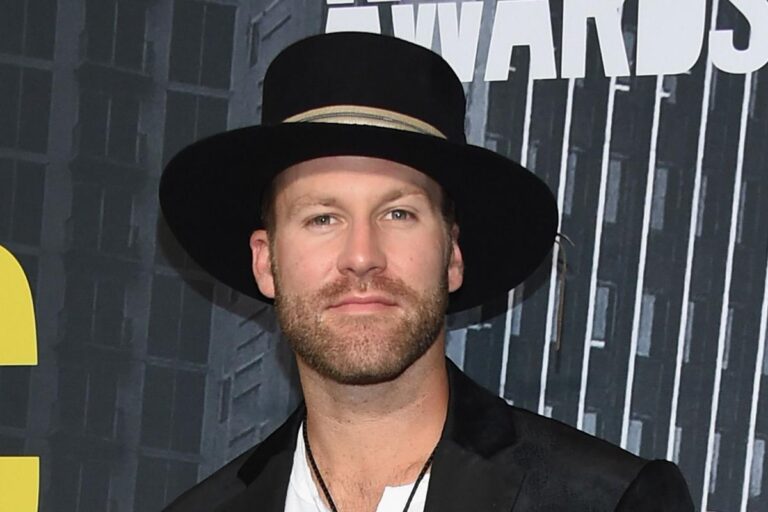

Four years later, Afghanistan has faded from headlines and those lifelines have frayed. Wasefi has submitted an asylum application to the U.S., while his siblings and family remain in Afghanistan. Jordon and Beckvold continue to field messages from stranded students they can no longer help. “We’re having a hard time,” Beckvold says. “There aren’t many embassies operating in Kabul, much less offering visas. There are a million of these stories, where no one has jobs and everybody’s hungry.”

Derek Beckvold (left) and Bob Jordon at the Longy School of Music in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

LONG BEFORE BOSTON, there was Farah: Afghanistan’s desert province, near the border with Iran, where Wasefi was born during the Taliban’s first regime, where the winters thundered with wind and summers blistered with intense sun. He was the second-youngest of nine siblings, with a stay-at-home mother and a father who worked at the Department of Agriculture. In a soccer-field-sized garden, the family grew pomegranates, jujubes, and other produce.

In 2007, when Wasefi was eight, an aunt brought him to Kabul — 16 hours away by bus, past many military checkpoints — and enrolled him at the Afghan Children’s Education and Care Organization (AFCECO), a refuge for orphans and children from distant provinces. His new home was a three-story building with yellow and green balconies that overlooked the city. Inside, about 30 children shared bunk beds; in the basement, a few years later, came the only baby grand piano in Kabul.

“The orphanage changed my life,” he says. He was struck by the way people from across Afghanistan’s ethnic groups got along. “Pashtuns, Uzbeks, and Hazaras lived as brothers and sisters under one roof. We spoke Dari or Farsi with different accents, teaching each other words from our dialects. It was there that I had the chance to learn music.”

Every morning at 7 a.m., a rickety school bus took AFCECO students to the Afghanistan National Institute of Music (ANIM), the country’s only Western music school. The institution had survived steep odds. During their first reign from 1996-2001, the Taliban had outlawed all music besides non-instrumental religious chanting, enforcing the ban with brutal tactics that included a suicide bombing at an ANIM student concert. Though unseated by the U.S. invasion in 2001, the fundamentalist group spent the next 20 years waging guerrilla warfare against the occupying force. By 2021, as the last American troops prepared to withdraw, the Taliban’s return to power was months away.

Students at AFCECO, including a young Wasefi (at left in the second row from the top).

Courtesy of AFCECO

When Beckvold and Jordon joined ANIM in 2012 and 2013, respectively, they were working musicians in their early twenties, fresh out of the New England Conservatory, walking dogs and working side jobs to stay afloat. They’d come to teach music theory and performance, but their real role was more like surrogate older brothers to their students.

“Music aside, it was a big, crazy family,” Beckvold says. “Even if you didn’t teach these kids, you knew them all by name, and they knew you. They’d just come into your room and talk. And that made the difference.”

ANIM thrived on Western attention: embassy concerts, sold-out shows at Carnegie Hall and the Kennedy Center, front-page coverage in The New York Times. “Visiting journalists from CNN or Al Jazeera often told the same story,” Jordon says. “‘Oh, look, music thriving in a barren land.’ It was a feel-good story coming out of Afghanistan, and there weren’t many of them.”

But reality was more nuanced. Though ANIM created genuine opportunities, resources sometimes ended up in surprising places. The school had a surplus of some items — like dozens of conga drums found in an instrument inventory, still wrapped in plastic — and a shortage of others, like student textbooks. Faculty members would sometimes show up for free lunch and leave, leaving students alone in empty classrooms.

Despite the difficulties of running a school in a war zone, ANIM created a space in Afghanistan where kids could befriend teachers from all over the world and earn the chance to leave later on. “It was our candle in the darkness,” Wasefi says.

Jordon, Wasefi, and Beckvold (from left).

Jordon and Beckvold each spent a year in Kabul, and went onto separate paths teaching music across the Middle East and South Asia for the next several years, before returning home. Their first refugee resettlement in the U.S. happened by accident. In 2015, two former ANIM students enrolled in a summer program on Long Island and decided they didn’t want to return to Afghanistan. Beckvold helped them decipher immigration options and find temporary housing. The students worked a graveyard shift at a Popeyes in Coney Island while they awaited results; today, one of them, Milad Yousufi, has won three Emmys, while the other former student started a career in Canada.

The following year, Jordon and Beckvold helped Tammam Odeh, a Syrian harpist, secure a scholarship to Bard College to avoid an army draft — only to watch Trump’s Muslim ban kill the visa at the last minute. Within Biden’s first week in office in January 2021, the duo contacted Bard again and restarted a visa application process, this time successfully. Their crash courses in visa applications and asylum law would prove essential when Kabul fell later that year.

WHILE ALL THIS WAS happening, Wasefi continued to study trumpet at ANIM. His parents often suggested he find a more reliable career than music. As the Taliban gained renewed prominence in Afghanistan — including in his village in Farah — they started to worry not only for his livelihood, but for his life. His visits home were carefully timed: weeklong trips every two or three years, short enough to escape notice. “I was afraid for my family,” he says. “But it was too late to change my path.”

After graduating from ANIM, Wasefi taught at the school and formed a girls’ choir, producing an album called Kid of War. He led a band called 99 Percent, inspired by his studies of class and socialism, playing “for the ordinary 99 percent of Afghans, the ones deprived of food or an education — and against the one percent of parliamentarians, thieves, and drug dealers who always controlled Afghanistan.” He developed his trumpet skills with Australia’s Peter Knight and Spain’s Guillaume Torró Senent in a fellowship offered by Teach To Learn, a nonprofit that Jordon and Beckvold founded after arriving back in America.

During his time off, Wasefi traveled across Afghanistan with his trumpet, logging his journeys on YouTube. In the summer before the Taliban invasion, he played in the Bamiyan caverns, where massive Buddhas had stood for 1,500 years before Taliban clerics had ordered them destroyed in 2001. In his video, Wasefi wears a red Che Guevara T-shirt and a purple hoodie.

In Jalalabad, a city east of Kabul on the way to the Khyber Pass, he played for village farmers who’d never seen a musical instrument. “One experience really changed my view of people like them,” he says. “I’d just finished a song and was about to start the next when the call to prayer started. It would go on for 10 minutes, azan after azan, spreading from one mosque to all the others around the village. We stopped playing, not wanting to be rude. But one guy stood up and said, ‘Please continue. We’ve heard many calls to prayer, but never this music.’”

Wasefi falls quiet as he revisits this memory. “It wasn’t their fault that they’d never listened to this kind of music. I was playing Western instruments. I’d gone prepared for them to hate me, to throw their shoes at me, and I told myself I’d still respect them. But they loved my music. Even as Muslims, and even during the call for prayer.”

THAT SUMMER, Taliban invasion of Kabul brought Wasefi’s travels to an abrupt end. Within hours, his world collapsed: Students went into hiding, and the Taliban claimed ANIM as a military base, broadcasting interviews in front of a mural of a cello and piano keys.

A frantic evacuation over the course of the next several months relocated more than 250 students across Europe and the U.S. Who made the lists involved luck, politics, and family trees. Weeks after the invasion, Wasefi helped load a full ANIM evacuation bus — ranging from teenagers learning their scales to the 85-year-old tanbur maestro Rasul Aziz — on its way to the airport. He took everyone’s attendance and checked papers. Then he said goodbye, shut the doors, and went home.

“I had no intention of leaving,” he says, shrugging. “I wanted to stay and make music.” He played in the hills at dawn and sent anti-Taliban compositions to international performers via email and messaging apps, including to a string quartet in Australia and musicians in Italy.

Back in Boston, Beckvold and Jordon received desperate WhatsApp messages from children who’d been left behind. They scrambled to help, joining a hastily assembled network of musicians, journalists, and aid workers who met weekly on Zoom to coordinate evacuations. They steered a Japanese relocation for Jamshid Muradi, a former flute student who’d performed with ANIM in America, and his sister, a judo champion who’d received Taliban death threats.

By winter, as conditions worsened, Wasefi’s family and friends begged him to leave. Before departing, he returned to the Taliban-controlled ANIM campus to retrieve his old trumpet. His sister pleaded with him not to risk meeting the Taliban, calling his mother in tears. A friend accompanied him to the gate, quickly swapping his clean phone for Wasefi’s as a Taliban guard approached.

“They checked my pockets and phone and took me to the instrument library. I pointed at my trumpet on the top shelf,” he said. “The commander brought it down and closed all the windows. He opened the case and looked at me. ‘Can you play this?’ he asked, and I nodded. ‘Then play the national anthem,’ he ordered.”

Wasefi hesitated, then started to play. “I hated the idea of playing for him,” he says. “But I wanted to touch my trumpet just one more time.”

After the song, there was an uncomfortable silence. When Wasefi asked if he could have his trumpet back, the commander’s face hardened. He was told to go home and repent.

Wasefi plays trumpet at a bridge in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

SHORTLY AFTERWARDS, Wasefi flew to Pakistan with a backpack containing his laptop and two hard drives of family photos and music, and applied to Boston’s Longy School of Music. He arrived in the U.S. on Aug. 11, 2022 — almost a year after the invasion. Through an email list run by a Boston nonprofit, Jordon and Beckvold were able to find Wasefi a place in the large pink home of Dexter Eames, an electronics engineer, and his wife, Sylvia Fine, a retired physician, a short walk from the Longy campus.

“He was painfully shy,” Fine tells me. “He sat here,” she says, gesturing to their wooden kitchen table, “and would only accept a cup of tea. He wouldn’t even take a cookie.” A few days later, on the anniversary of the Taliban takeover — which Wasefi calls his country’s “black day” — they talked for hours. “Some of his school friends living abroad were extremely depressed and probably borderline suicidal,” she said. “He worried about them.”

Around that time, photos of the Taliban burning musical instruments in Herat, near Wasefi’s hometown, circulated online. Four men, clad in white with black turbans, face a pile of instruments on fire. Visible in the torched pile are amplifiers, wires, and a guitar case. The flames are brilliant orange, cut against black smoke and the blue horizon.

Eames and Fine found an attorney who offered to help Wasefi apply for asylum, an application he was sad to complete. “He felt like he was deserting his country,” Fine says. “He cares a lot about women and music. And he was determined that he’d be back.”

Taliban officials burn confiscated musical instruments in a bonfire.

Salampix/Abaca/ZUMA Press

In his early months in the U.S., everything felt foreign. “Even greeting people was different,” he says. “Sometimes when I saw people, they didn’t even say hello. In Afghanistan, they’d at least take a minute or two to ask how you’re doing. And they’d really mean it.”

At Longy, while classmates entered competitions and chased prestigious symphony positions, Wasefi spoke of returning to Afghanistan’s provinces to teach music. “Performing here — it doesn’t give me pride,” he says. “Even if I write the first symphony from Afghanistan — so what? My family back home wouldn’t know these words.”

He mentions a bittersweet memory of the first time his mother told him she’d come see him play, just weeks before Kabul fell. “The concert she was going to come to never happened,” he says. “I want to take my music back to her. It’s one of my dreams.”

Wasefi’s trumpet bag features a map and flag of Afghanistan.

Back at the taqueria, Jordon and Beckvold sit next to Wasefi and another ANIM graduate, Arson Fahim, with the ease of old friends, four bodies pressed together on a bench built for two. A decade ago, they were playing music in a war zone. Now, they share quesadillas in Harvard Square while tourists stream past the windows. American musicians who taught in Kabul, Afghan refugees in limbo in the U.S.: all of them here, sometimes fighting over who is better at chess.

Beckvold recently became executive director of the Portland Symphony Orchestra in Maine after serving as managing director at the Boston Philharmonic, where Jordon now works as director of development and marketing. Beyond their day jobs, they run Teach To Learn, now a wide-ranging virtual network that has grown to connect musicians and educators across more than 40 countries. They’re still trying to help former students, many of them homeless and in hiding in Afghanistan.

One of Jordon’s former drum students, Mehran, has made three trips to Pakistan for visa appointments — each costing a handsome re-entry fee — only to be told to fill out another form and return in six months. Beckvold’s former saxophone student Elham was denied entry twice into Turkey and traveled to Iran to flee the Taliban, sleeping on park benches before finding work at a car repair shop. He was deported back to Afghanistan and lives in hiding with his parents, who are also musicians. Both men had performed at Carnegie Hall as children and were seeking P-1 performer’s visas to the U.S., but those pathways have stalled under the Trump administration. (Both performers’ last names have been hidden for their safety.)

The weight of running this informal refugee network shows. “I’ve received so many messages from strangers asking for help,” Jordon says. “I’ve stopped responding to a lot of them. How do you choose who to help when everyone is desperate?”

Wasefi plans to enroll in Tufts for a master’s degree and is working on the Afghanistan Freeharmonic Orchestra, a virtual group of refugee musicians from his country that includes many friends from Kabul. This summer, he organized a house concert in Cambridge where he performed traditional Afghan pieces with an ANIM classmate who evacuated to Portugal before settling in Boston. AFCECO, the orphanage that once housed him, now runs underground safehouses in Afghanistan to educate and resettle girls, thanks to which his cousins were able to move to New York to attend the Marymount School.

Beckvold, Jordan, and Wasefi in a Longy classroom.

Many Americans tell themselves a sanitized story about Afghanistan, to the Taliban’s likely delight. Some articles in The New York Times and YouTube videos by Western influencers marvel at Afghanistan’s relative calm, focusing so intently on the drop in violence that they barely mention the women who can no longer work, study, or appear in public without male guardians. For people like Wasefi, with sisters and nieces back home, no amount of tourist-friendliness can compensate for this disaster.

Afghan refugees like him await their asylum decisions in an increasingly hostile climate marked by ICE raids and deportations. Several of his friends and peers have moved out of Boston for their own safety. They are all here legally, Wasefi notes, “but that doesn’t seem to matter much based on the news.”

The persecution feels familiar to his family. After 15 years in Isfahan, Iran, one of his sisters and her children are being forced back to Afghanistan due to mass deportations and vigilante violence against Afghans in that country — including legal residents. One of her Afghan neighbors was recently murdered by a gang in his bedroom, with his son watching. “I told her America is becoming like Iran for Afghans, and she was shocked,” Wasefi says. “We aren’t telling our mom. She would worry.”

Still, he resists the language of borders. “I don’t really like to call myself an immigrant,” he adds. “It feels weird, almost like betrayal. We’re all immigrants, in a way, since traveling has been part of our lives for centuries. Humans, like birds, move with the seasons to survive.”

Today, most of his family remains in their village, where his brothers farm cucumbers and tomatoes. Their childhood neighbors have split between joining the Taliban and fleeing to Iran. Wasefi stays in contact with his family via WhatsApp. The internet is spotty in the village, which means voice messages every week or two, and no FaceTime. He hasn’t been able to send them much of his music. And he isn’t sure if or when he will be able to go home.

I tell him that despite everything they’ve gone through, they must be proud of him.

“Hopefully one day,” he says.