AC/DC can thank Who legend Pete Townshend for helping to power up the next chapter of their career at the beginning of the ’90s.

That’s just one revelation that you’ll find within the pages of the new memoir from Derek Shulman. The former Gentle Giant frontman is universally beloved by progressive rock fans. But for other music aficionados, it’s very possible that they might have seen his name for the first time in the liner notes in a different way, thanks to a secondary career which found him discovering and/or signing bands like Cinderella and Bon Jovi to their major label deals.

His success on the industry side grew to the point that he got the keys to his own label, shepherding a new chapter at ATCO Records. He inked Dream Theater and Pantera and also helped Bad Company land their next big hit record. But how does the Gentle Giant guy end up going to the dark side?

“I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do next,” he tells UCR, remembering the moment that he was mulling his future after Gentle Giant disbanded in 1980. As it happens, his former job would help him to get his next one. A friend who worked at Chrysalis, one of the label homes for the band’s last five albums, phoned him to let him know there was an opportunity at Polygram. He urged Shulman to think about taking the meeting.

Eventually, he acquiesced. “I went over there and met with the team at Polygram,” he recalls now. “The fact that I knew a lot of people out there, you know, there’s a couple of major radio consultants who were big Gentle Giant fans. Being able to get to them, I got the job and I became Darth Vader.

Shulman’s new book, Giant Steps: My Improbable Journey From Stage Lights to Executive Heights, chronicles his incredible journey on both sides of the music business. In this exclusive excerpt, he details how AC/DC — who had released some of their early albums on ATCO — eventually returned to the label. It was a crossroads moment in the band’s career which ended up paying off in a big way.

How AC/DC Found a New Home

ATCO was an artist’s label, and the focus was primarily on music—or at least that was my goal—but since the label was an Atlantic imprint when I came on board, as opposed to an independent company, there was some carry-over from other parts of the Warner family, which is how we secured some of our acts. There was also a certain amount of bartering we had to do to secure the artists we wanted. At the time, AC/DC were on Atlantic and were on the verge of being dropped. They were in a downward tumble and hadn’t released a full-length original album since 1985’s Fly On The Wall, which tanked. They could still fill venues on tour, but it looked like their best days were behind them and they would soon become a legacy band playing package tours in summer sheds.

That would have been a shame, since they could still put on a great live show and were still talented artists who, I felt, still had plenty to offer. I thought they deserved a chance to redeem themselves, but the company was looking at paying them one million dollars for the next album they delivered. ‘Ah, you can’t drop AC/DC,’ I told Doug Morris, who I tried to be as civil with as possible, even though I knew he had argued against me running ATCO. ‘AC/DC has nothing left,’ he said. ‘And I don’t see it happening in this music climate.’ ‘What are you talking about?’ I said. ‘It’s AC/DC. They’re legends.’ ‘Well, if you want to take them over to ATCO and try to get them to do something real, maybe we could trade. If you give me Pete Townshend, I’ll give you AC/DC. Otherwise, I’m gonna drop them.’

Watch Derek Shulman and Tony Visconti Discuss Derek’s ‘Giant Steps’ Memoir

‘It’s a deal,’ I said. Pete Townshend was in the grandiose concept solo album phase of his career. In 1989, he did Iron Man: The Musical, which featured Pete, John Entwistle, and Roger Daltrey on two songs, as well as special guests Nina Simone and John Lee Hooker, but it still flopped. No one wanted to hear Pete Townshend doing conceptual music outside of the Who.

READ MORE: Pete Townshend’s ‘Iron Man’ Leads to Who Reunion

By contrast, AC/DC were still gods of rock’n’roll. I thought that if they had the right support, they could write another hit album. It was about time. I made the trade with Doug, and I looked forward to the challenge of working with the band. AC/DC had never allowed anyone from Atlantic into the studio before, and they were reluctant to play the record-company game. I thought having a history as a recording and touring artist might encourage them to be more open with me than some of the pencil-pushing label guys they were used to. I wanted them to see me as someone who was on their side and had done what they’d done. I hoped my insider angle would pay off, and I had some connections to them that I thought might thaw the ice.

When I was in Simon Dupree & the Big Sound, we had played some festivals with the Easybeats, the band that featured Angus and Malcolm Young’s brother George as well as Harry Vanda, who co-produced AC/DC’s early albums. Plus, I had produced Gentle Giant albums, and I knew working closely with producers was important to AC/DC. I also knew their managers: Stewart Young, who also managed Emerson, Lake & Palmer; and Steve Barnett, who worked for Gerry Bron. I called Stewart to talk about AC/DC moving over to ATCO and said, ‘I’d love to work a little bit with Angus and Malcolm when they’re in the studio, if that’s okay with them.’ To my delight, they were fine with it. They were ecstatic about being off Atlantic as the guy who signed them had left the label and they no longer felt connected to the company. They were pleased that their new label head understood music—not just business—and were interested in working with me to help them revamp their sound. Knowing that a great producer could help put them back on track, I called Bruce Fairbairn, who was excited to be asked to work with the band. (I mean, really, Bob? Who doesn’t like AC/DC?)

AC/DC Starts Work on Their Next Album

They went out to Bruce’s place in Vancouver and felt invigorated working on a new record for a new label in a new environment. In a way, it was a rebirth, and suddenly they felt more inspired and creative than they had in ages. It’s so easy to be complacent about new AC/DC songs. Even the band members recognize that everything they do is going to sound inimitably like AC/DC. They’ll never branch off in a crazy art-rock direction or add samples and electronic beats to their music. At the same time, while there are bands that can approximate AC/DC’s bluesy hard-rock sound, no one can effectively imitate it in a meaningful way that stands the test of time. That said, it’s easy to listen to a new AC/DC riff and say, ‘Yeah, it sounds like AC/DC.’ But it’s harder to know right away if it’s going to be good AC/DC or classic AC/DC.

The Secret Sound of AC/DC

I went to Vancouver a number of times to check on the band’s progress and help with some of the song arrangements. Welshman Chris Slade was drumming for them at the time, on what would be his only record with the band. He replaced Simon Wright, who had left to join Dio. Angus Young told Chris not to play any drum fills or breaks whatsoever, just kick drum and snare. Unconventional as this was, it turned Chris into a metronome, and he kept perfect time. In most other bands, a drummer who doesn’t swing or play fills would make the music sound stagnant. But as I learned by watching them in action, the rhythmic surge and punch in AC/DC came from the rhythm guitarist, Malcolm Young, and he’s a large part of the reason why they were so incredible. You don’t realize it until you see the process unfolding, and it’s fascinating to watch. Everyone in the band understood that Malcolm was the anchor and root of every song, and he had such a great connection with his brother, Angus, that Angus could intuitively play leads and fills on top of Malcolm’s riffs and they always filled any gaps and perfectly complemented the rhythm parts.

‘The Razors Edge’ Introduces AC/DC to a Whole New Generation

The chemistry between them was explosive, and the rest of the band fleshed out the sound. If there was a break in a song, it was followed with a resounding boom that released all the built-up tension in a rush of sound. AC/DC perfected this formula years before they signed to ATCO. Maybe they became complacent at a certain point. But there was a new energy to the songs they worked on with Bruce for The Razors Edge. The opening rapid-fire hammer-on and pull-off thing Angus does on ‘Thunderstruck’ is as iconic as Eddie Van Halen’s solo in ‘Eruption,’ and perhaps even catchier. As the song builds, Malcolm turns up the heat with a funky little part, and the song his critical mass with the pre-chorus before lightning strikes in the chorus. Genius.

READ MORE: The Most Overlooked Song From Each AC/DC Album

Watch AC/DC’s ‘Thunderstruck’ Video

I have to admit that as great as that song was, I felt that ‘Moneytalks’ should be the first single. It surged at a mid-tempo, it was more simplistic, and I thought it contained the most accessible hook on the album. Angus and the band’s managers all thought we should go with ‘Thunderstruck,’ so we did, and it blew up. That confirmed something I had believed for years: by far the best A&R guys are musicians. They’re the ones who know their fans and the marketplace the best. The Razors Edge was a global sensation that hit like a cluster bomb at just the right time. ‘Thunderstruck,’ ‘Moneytalks,’ and ‘Are You Ready’ all became go-to radio tracks, and the album hit #2 on the Billboard 200 and remained on the chart for seventy-seven weeks straight. Bruce also produced the 1992 album AC/DC Live, which was recorded during the tour for The Razors Edge and was also a big success.

Derek Shulman – Giant Steps

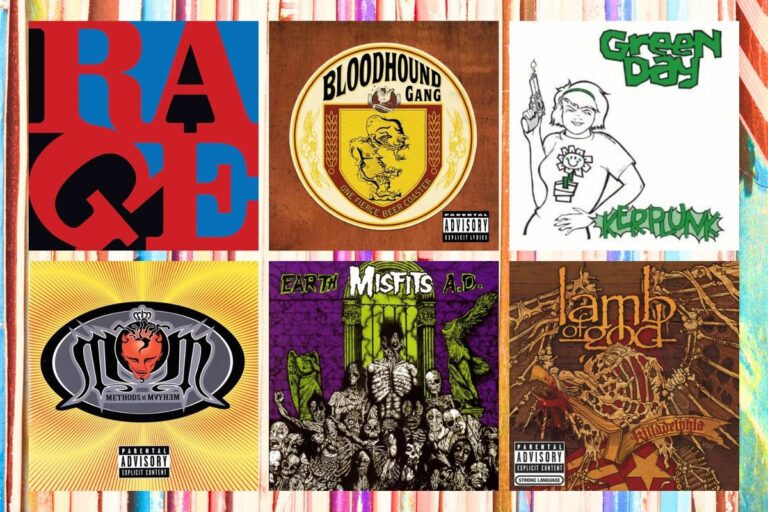

2025 Rock Books

Memoirs, photography and more.

Gallery Credit: Allison Rapp