Tom Scholz built Boston’s sound in his basement, pioneering recording techniques that redefined arena rock. But by the early 1980s, his perfectionism and resentment of the industry brought the band to a standstill and put him on a collision course with CBS Records chief Walter Yetnikoff.

In this exclusive excerpt from Power Soak: Invention, Obsession and the Price of the Perfect Sound, journalist Brendan Borrell tells the story of a remarkable meeting between Scholz and Yetnikoff about Scholz’s long-delayed third album, Third Stage. In order to tell this story, Borrell conducted new interviews and gathered thousands of pages of forgotten documents from federal archives, courthouses and personal collections of the participants.

Most working musicians aren’t Bob Dylan or Paul McCartney. At best, they have only one great album in them, perhaps one unforgettable song. To make a living in this business, everyone knew you needed to milk that early success for all it was worth.

Boston’s demanding contract with CBS Records required that they churn out one to two albums per year. Almost nobody ever met such absurd deadlines. But no one so flagrantly blew past them like Tom Scholz.

How the Trouble With Boston’s Next Record Came to a Head

His third album was now three years late under the original contract, and it was still late under all the extensions he had been granted. In May 1981, Scholz sent a Western Union message to CBS Records chief Walter Yetnikoff, blaming the delays on everyone but himself:

MANY PROBLEM AREAS HAVE COME UP CONCERNING THE RELEASE OF THE

NEW RECORD. SOME HAVE BEEN UNSUCCESSFULLY PURSUED THROUGH THE

EPIC STAFF. OTHERS REQUIRE YOUR DECISION AND AUTHORIZATION. IT’S

OBVIOUS YOU DON’T HAVE TIME TO CONSIDER THESE PROBLEM AREAS AT

THIS TIME … THE ALBUM DELIVERY WILL BE POSTPONED.

The Showdown

By the time Scholz walked into Black Rock a few months later, Yetnikoff was in a mood.

Whether or not a Screwdriver helped him get there, as it often did, is hard to say. Sometimes a line of coke sufficed. Whatever the fuel, Yetnikoff sat Scholz down like a Mafia don ready to make a point.

He started with a story.

One of Epic’s other bands, Cheap Trick, hadn’t delivered new material for almost a year. They were holding out, Yetnikoff said, hoping to renegotiate their contract. In return, CBS had slapped them with a $52 million lawsuite.

Yetnikoff made sure he had Scholz’s attention. “CBS can be a real prick when it wants to be,” he said. Then, after a pause, he repeated the sentence word-for-word.

How Did Scholz Respond?

He then turned to the matter at hand. Scholz had promised him the next album this fall. Was it coming? Recording had been a grind, Scholz said, but with the dispute with his manager, Paul Ahern, resolved, he was making headway. He envisioned a theme album: a personal statement, not just a commercial product, something that echoed his own internal shift as he moved past early adulthood and imagined what kind of man he aspired to be.

He even had a tentative title: Third Stage. One ballad, “Amanda,” was nearly finished.

Listen to Boston’s ‘Amanda’

Could he deliver by year’s end? Possibly, he said. He had been busy recording with his drummer Sib Hashian and bassist Fran Sheehan.

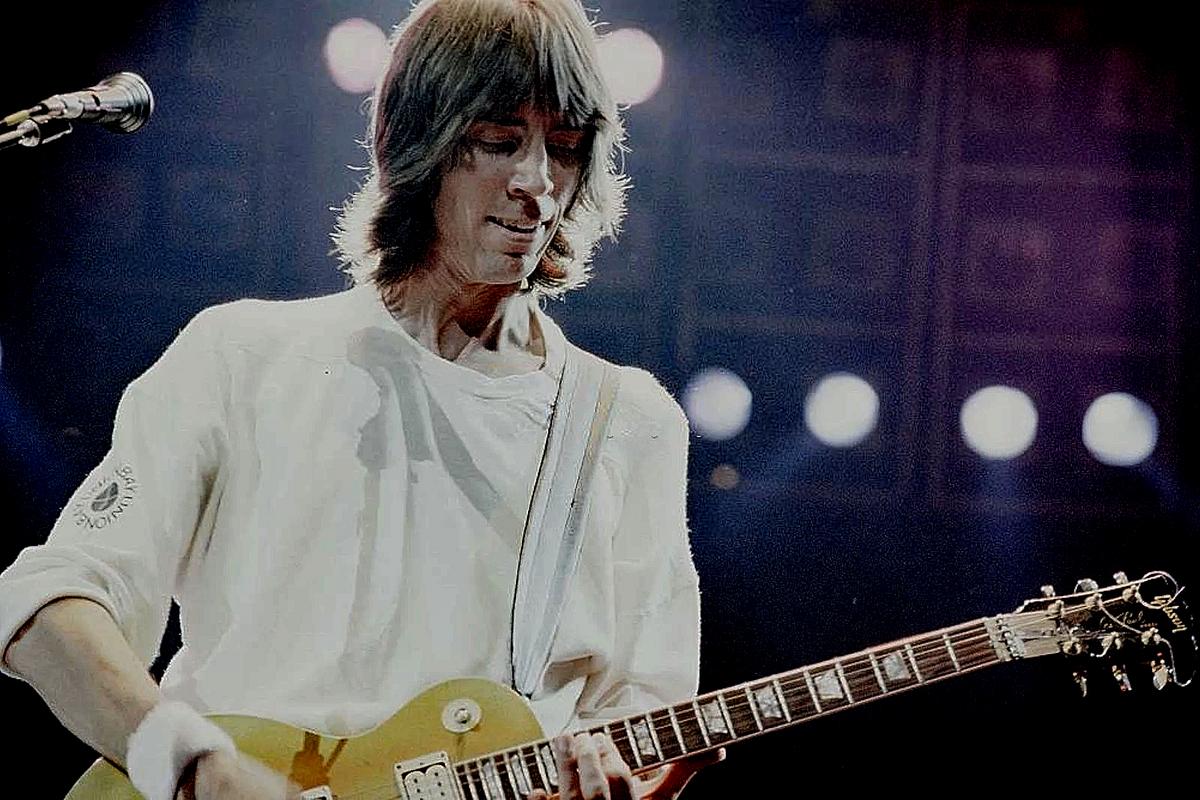

Yetnikoff knew that Scholz had lost his guitarist, Barry Goudreau, and he wanted to know whether Goudreau’s brother-in-law, Brad Delp, would still be singing on it. Delp’s voice and sensibility infused much-needed emotion into Scholz’s overengineered compositions. When Scholz retreated to his hotel room after a show, it was Delp who stayed late after concerts to sign every T-shirt and album cover.

The Mastermind Had a Surprise

Scholz admitted to Yetnikoff that Delp’s status was uncertain. Delp had done some studio work, but he wasn’t sure if he would tour with the band again.

Human relations may not have been Scholz’s strong suit, but problem-solving was. He presented Yetnikoff with a new tape of an old song.

The stereo whirred to life. “A Man I’ll Never Be” emanated from the speakers, a track from the band’s second album. Butter-smooth vocals rose above Scholz’s moody piano and organ tracks along with those powerful guitars. Yetnikoff listened intensely. Then came the reveal.

Scholz explained it wasn’t Delp’s voice Yetnikoff was hearing. Or it wasn’t just Delp’s voice.

How it Happened

After the release of Goudreau’s solo album, Scholz had mounted a “one-man campaign to canvass the country” to find a replica who had Delp’s “identical vocal sound.” He placed an anonymous ad in the back of Rolling Stone: “Wanted: Rock Singer $50,000 minimum guaranteed first year.” Candidates were instructed to send a tape to a P.O. Box in White Plains, New York, demonstrating their ability to channel Chicago, Foreigner, Bad Company and, of course, Boston. “Acceptable applicants will be auditioned live, expenses paid.”

Thousands applied.

Scholz discovered the acoustic match in a man named Mark Dixon, who sang for a cover band in a converted bowling alley in Niagara Falls, New York. Scholz brought him to his basement to record. On the track Scholz played for Yetnikoff, every line alternated between Delp and Dixon.

What Were the Results?

Neither Yetnikoff nor Scholz could tell the difference.

Scholz said he hoped to use both vocalists on his album, but if Delp bailed, Dixon would tour. If Yetnikoff approved, Scholz would put Dixon on the band’s payroll. Yetnikoff gave it his blessing but added: keep it quiet. No one else needed to know, inside CBS or out.

It was another one of their private understandings.

READ MORE: How Boston Reached New Chart Heights With ‘Third Stage’

Excerpt from Power Soak © Brendan Borrell

Power Soak Book

Boston Albums Ranked

Their debut album remains an all-time bestseller, but over the next four decades, they’ve released only five more LPs.

Gallery Credit: Michael Gallucci